An Empirical Look at Recent Circuit Splits and the Likelihood of Supreme Court Review

Circuit splits are the clearest indicator of cases ready for Supreme Court review, but the Supreme Court only selects a subset of these on cert. This post assesses some of the most likely candidates.

People often say the Supreme Court takes cases to fix “circuit splits.” These splits are actually one of the few things baked into the cake of the one Supreme Court Rule that says anything about the factors the Court considers when it reviews cases for cert grants. The real question is which splits—and why these, not those. Scholars like Aaron Bruhl have warned that even counting splits is tricky, and that our measuring sticks can skew what we think matters. Others show that conflicts do help drive grants, but not on autopilot: the Court’s appetite rises and falls by subject, posture, and timing. And sometimes, even with a clean conflict on the table, the Justices step around it because the case is a clunky vehicle—for example Article III standing fights in class actions, where procedure can swallow the question.

Here is how the article proceeds. First, it focus on real, on-the-record disagreements: the dataset counts a split only when a federal court of appeals opinion overtly said there was one—not just where commentators suspected a conflict. That keeps the universe concrete and reduces guesswork. Second, for each decision I ask two simple questions: How big is the question and how ready is this case for the Supreme Court review? The first—call it Importance—looks at the reach of the ruling (local vs. national), how deep and widespread the conflict is, whether the opinion is unpublished, published, or en banc, how foundational the doctrine is, and whether the stakes are niche or industry-wide/government-wide. The second—call it SCOTUS Likelihood—translates visible signals into rough odds: explicit or entrenched splits, en banc treatment, nationwide stakes, and stays pending appeal push the odds up; classic “vehicle problems” (mootness risk, forfeiture, messy remedies) pull them down.

Why separate the two? Because the Court doesn’t take every split and it doesn’t necessarily take the biggest question first—it often takes the cleanest version of a big question, or a repeat issue that’s perfectly teed up. Putting Importance and SCOTUS Likelihood side by side lets us see where the Court is most likely to move next, where important questions are stuck waiting for a better vehicle, and why geography is only one variable among many. The sections that follow start with quick comparisons across issues and circuits, then zoom in on a few top vehicles to show, in concrete terms, what makes a split ripe for review—and what can still derail it.

The Empirical Landscape

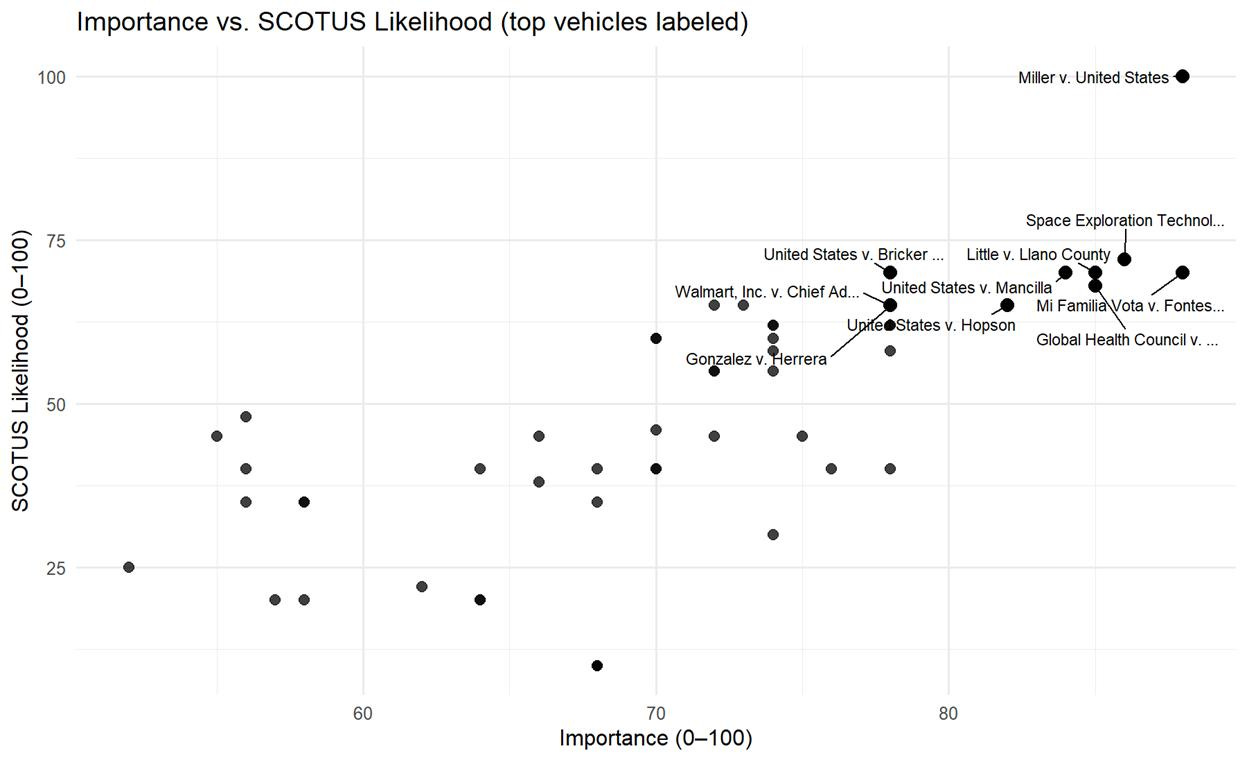

This analysis covers sixty split-driven appeals. On simple buckets, about four in ten cases fall in the High/Very High range for likely Supreme Court review, about one in three in Medium, and about one in six in Low. “Very High” is rare in this set—just a single case. In other words, the Court has plenty to choose from, but only a minority of conflicts look truly primed right now. And the two things this article tracks—how big the question is and how ready the vehicle is—move together strongly but not in lockstep. Bigger questions tend to look more grant-ready, but not all of them do. Here is how this looks graphically.

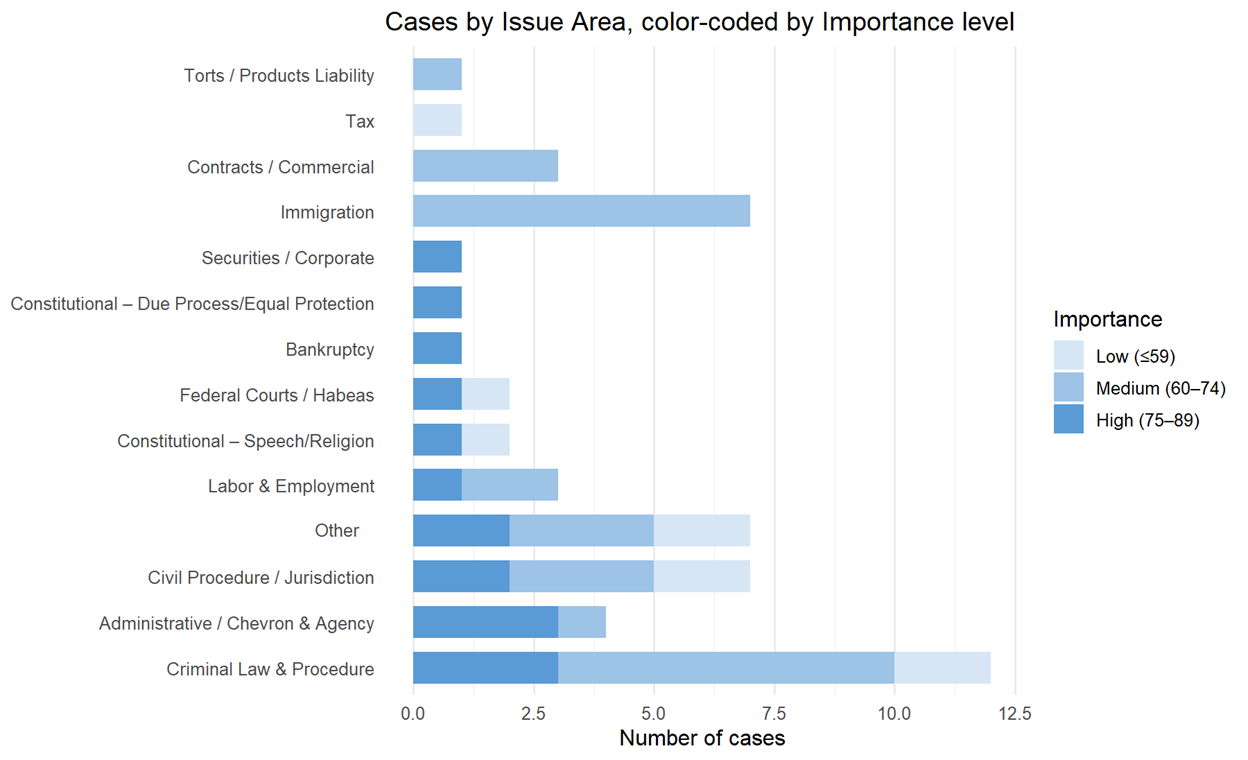

Where do the conflicts sit? A few subject areas consistently produce cases that look ready. In administrative/agency disputes, every case in our file lands in the High range; they pair national reach with clean, repeatable questions. Labor and employment looks similar—again, national stakes and relatively tidy records. Immigration is more mixed: a healthy share ends up in the top buckets, but a good number stall in the middle because timing and posture often complicate the ride. By contrast, criminal procedure generates many conflicts, yet fewer of them look cert-ready; fact patterns and remedies keep getting in the way. And civil procedure/jurisdiction shows the classic gap: important questions, but fewer vehicles that a grant can ride on without distraction.

What design and posture do. Two structural features carry real weight:

How many courts are in play. When a conflict is entrenched across multiple circuits, cases are roughly four times as likely to land in the High/Very High range as when the fight is still inside a single circuit. That’s the clearest force multiplier in the file.

How plainly the split is flagged. Opinions that say the quiet part out loud—“there is a circuit split”—populate the higher buckets far more often than opinions that gesture at “approaches vary” or “methodological differences.” Clarity helps the Justices see the payoff of a grant.

A smaller but telling marker is the vote line. Cases decided 2–1 are more likely to show up in the top buckets than unanimous panels. That doesn’t mean dissents cause grants; it does mean a calling dissent both sharpens the issue and signals that lower-court judges believe the question needs national resolution. They are also signals that the justices listen to, especially when they come from judges they trust.

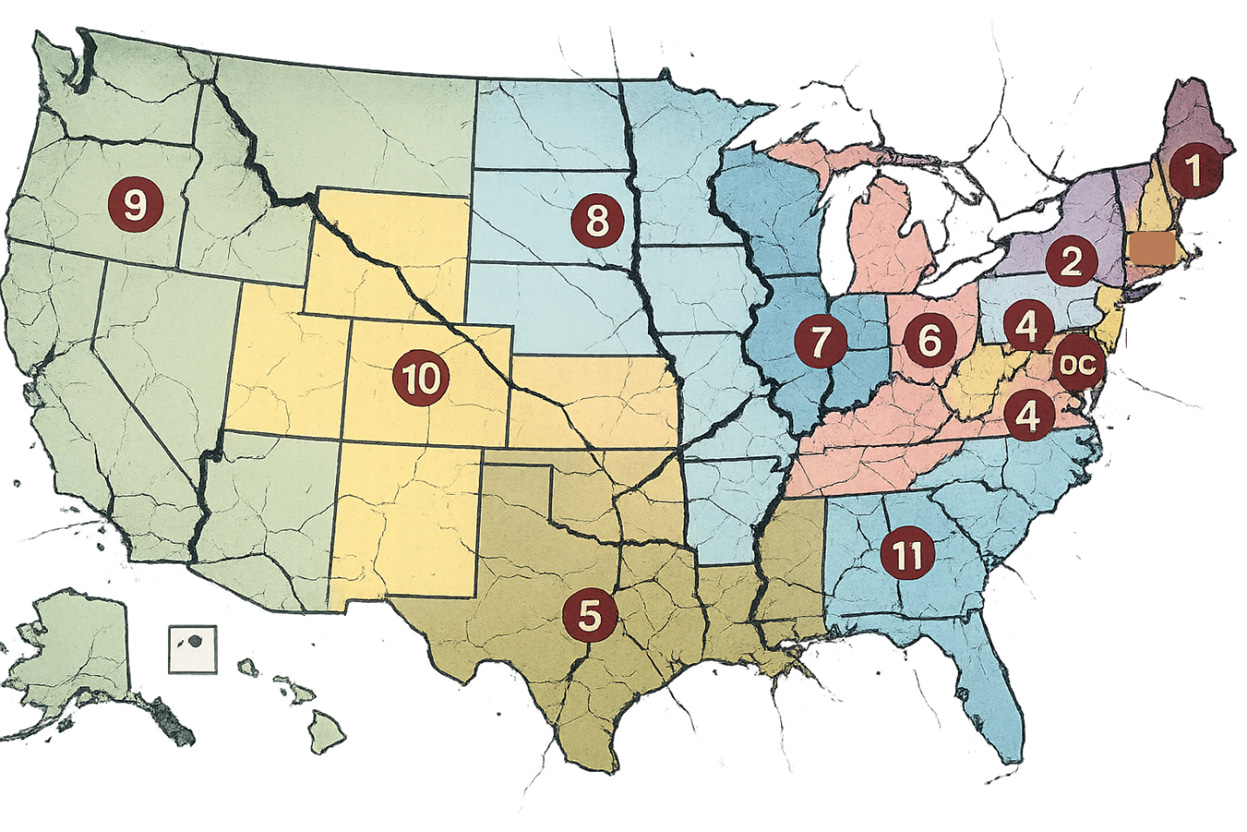

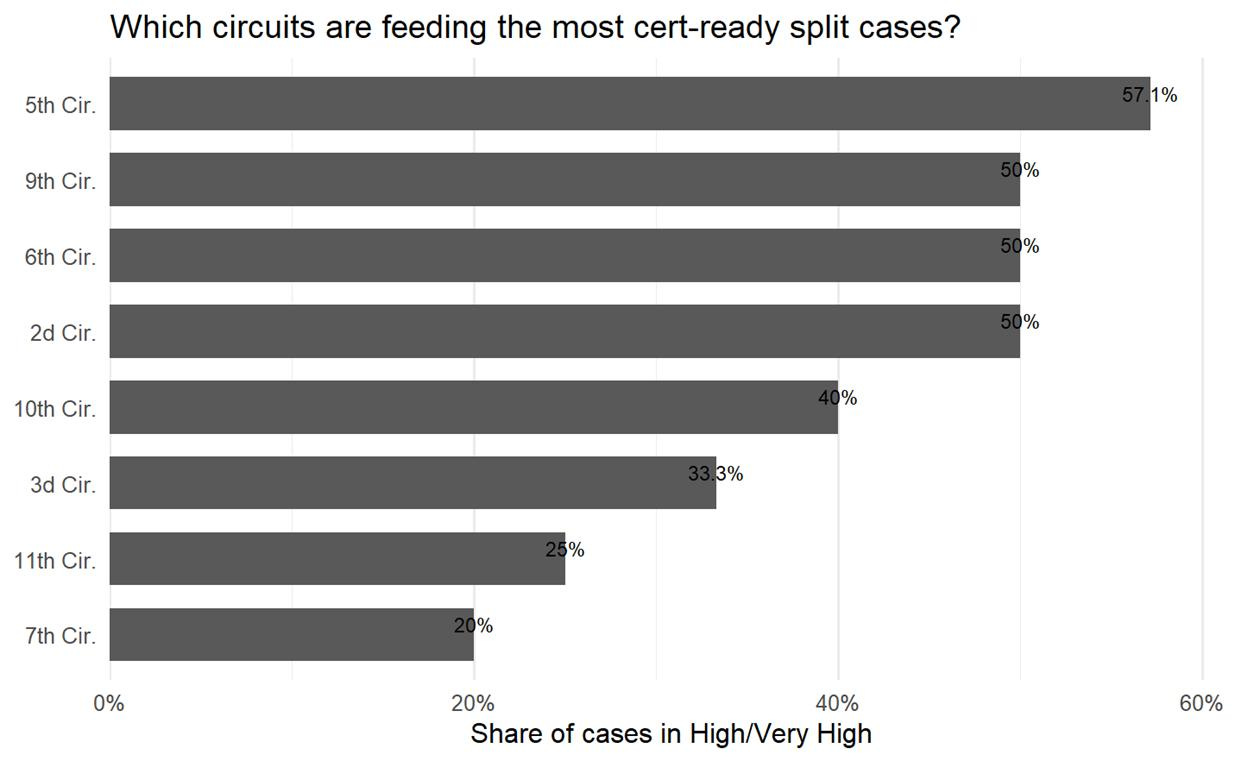

Circuit profiles, with a caveat. Looking across courts, some circuits are currently producing a higher share of cases in the top likelihood buckets—the Fifth most of all—followed by the Ninth, Sixth, and Second in roughly similar territory. This tracks with the high number of grants recently coming from the Fifth. Others—like the Eleventh and Seventh—tilt more toward the middle and lower buckets in this snapshot. Treat those as profile but not more than that: issue mix and posture do most of the work here, and counts vary by circuit.

The Court moves fastest when conflict severity and vehicle quality line up. Multi-circuit entrenchment, overt split language, and a clean record (often with a dissent that frames the question) push cases into the top range. Some areas—administrative and labor—get there more often because they bundle national stakes with manageable posture. Others—civil procedure and much of criminal—still matter a great deal, but the vehicles often need another turn of the crank before they’re truly grant-ready.

What actually pushes a case toward review

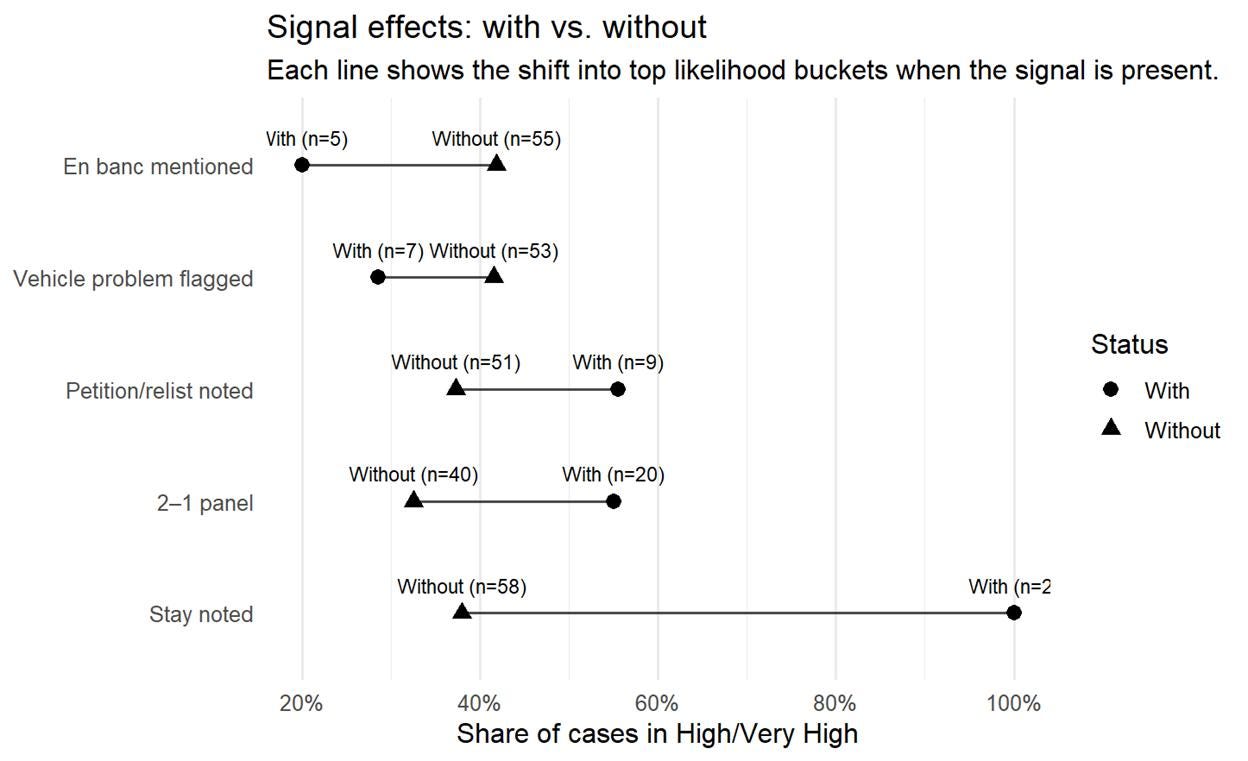

The data track the text in each opinion for on-the-record signals—things like stays pending appeal and en banc references. The analysis also used the panel vote line and flagged classic vehicle problems (mootness, standing, jurisdiction, waiver/forfeiture, remedial tangles) to look at what tends to show up in the High/Very High buckets.

Stays are a rocket booster. When a stay is noted, the cases sit in the top likelihood buckets each time, and the average likelihood score jumps by about 24 points compared to similar cases without a stay (roughly 71 vs. 46). The sample is small, but the direction is clear: when timing pressures are big enough to warrant a stay, the Court’s attention may already be engaged.

A 2–1 panel helps—mainly by framing the conflict. Split panels show a 55% rate in the top buckets, compared to 33% for other panels. The average likelihood score is basically a wash (about 47 vs. 48), which suggests the real value isn’t raw probability so much as issue-sharpening: a dissent that crisply frames the disagreement makes the conflict—and the stakes—easier to see.

Vehicle problems do real damage. When the cases flag mootness, standing, jurisdiction, waiver, or remedial snags, the share of cases in the top buckets drops from about 42% to 29%, and the average likelihood falls by about 7 points. Big questions can still be important, but messy posture often means these cases will not go to the Supreme Court for review.

En banc mentions are noisy in this cut. En banc cases show a lower share in the top buckets (20% vs. 42% otherwise) and a lower average likelihood (down approximately 10 points). The catch: several of these are rehearing-denied or otherwise ambiguous, not clean en banc merits decisions.

Read together, the signals line up with common sense. The Court moves quicker when urgency (stays) and intent are visible, when the conflict is crisply framed (2–1 with a focused dissent), and when the vehicle is clean (no jurisdictional or remedial traps). En banc related decisions don’t, by themselves, tell a stable story here—context matters.

Urgency, clarity, and cleanliness are the quiet forces behind cert. Show the Court a mature, multi-circuit conflict on a clean record, signal that the case is teed up now (petition/relist, sometimes a stay), and avoid the vehicle tripwires—and the odds should move noticeably in favor of Supreme Court review.

Concrete Examples

The patterns in the numbers come into focus once you put real cases on the table. Three examples—drawn straight from the spreadsheet—show what a strong vehicle looks like and why some questions move faster than others.

Start with Miller v. United States from the Tenth Circuit. On any common-sense view, the question matters: how sovereign immunity interacts with avoidance actions is not a boutique fight; it sets day-to-day rules for trustees and the federal government. The case scores at the top of our scale on importance (88/100) and, tellingly, at 100/100 on the likelihood metric. That’s what “ripe” looks like in the wild. The record is clean, the opinion is published, the stakes are national, and the conflict isn’t hand-wavy—it’s acknowledged. Geography helps here, but not because the case happens to be from one circuit rather than another; it helps because the disagreement has spread far enough, and clearly enough, that one decision can settle practice across the system.

A different domain—administrative law—shows the same basic shape through SpaceX v. NLRB in the Fifth Circuit. Post-Loper, structural and remedial questions about agencies are felt nationwide, and the opinion does the reader a favor by mapping the conflict expressly. That kind of candor matters. It tells the Court a grant will do real work, not just correct an outlier. The posture is tidy: a published decision that frames the legal dispute without turning into a remedial tangle, and a 2–1 panel that sharpens the issue rather than muddies it. Our scores reflect the package: high importance (mid-80s) and a High likelihood (low-70s). There are still moving parts—parallel matters and remedy scope can introduce timing friction—but as a vehicle, this is what “teed up” looks like: clear split, national stakes, and a question the Justices can answer without rewriting the record.

The third example, Mi Familia Vota v. Fontes from the Ninth Circuit, shows how urgency and posture interact in election-adjacent disputes. The grist is civil-procedure and jurisdiction, not merits questions about voting rights, but the practical stakes are large because timing turns ordinary doctrine into calendar-driven policy. The decision is published, en banc rehearing was denied with multiple dissents, and the notes in the file tie the issue to prior Supreme Court stay activity. That combination—explicit conflict, fully aired disagreement inside the circuit, and evidence that the Justices are already watching the space—pushes the case into the High bucket on likelihood (around 70/100) with an importance score right at the top of our range (88/100). The caution is baked in: election calendars can both accelerate and derail review. A clean record and a tightly framed question reduce that risk; they do not erase it.

Across all three cases, the constant is not geography for its own sake; it’s clarity—of the split, of the question presented, and of the record the Court would review.

Here’s where the analysis points: if you want review, build the case the Court actually takes. Draw the split with a map, not a gesture—who is on which side, on what precise question, and with what consequences outside the parties. Keep the record tidy so the Justices can say something about law rather than procedure. Show why the answer matters nationally, not just locally, and why this file—this posture, this timing—is the right vehicle. The cases that rise to the top in our set have those traits in common: an entrenched conflict, a clean question, and stakes that travel.

If you’re resisting review, press the parts that are key review factors. Show that the conflict is younger or narrower than advertised. Surface the snags that would force the Court into process instead of substance—mootness risk, preservation problems, remedial thickets. You’re not arguing that the issue is trivial; you’re arguing that this isn’t the version worth spending a grant on.

Trial and appellate judges have a role here, too. When a real conflict exists, say so plainly and say what it is. En bancs can help when they sharpen the question rather than diluting it. Opinions that identify the disagreement, mark its reach, and keep the record workable help the system move important questions on a schedule that looks like law, not chance.

This is about craft. Urgency that is visible (stays), conflicts that are explicit (not euphemisms about “approaches varying”), and vehicles that are clean tend to move. Geography helps when it reflects genuine spread, not a single outlier. Big questions still wait if the posture is messy. The Court’s agenda, in other words, is shaped by how well a case carries the issue. When the conflict is mature, the record disciplined, and the stakes national, the path to a grant is shorter and straight.

** This post was made possible with research and support of Daniel Thompson.

To subscribe, share or comments:

Intriguing. Another landscape I’ve never knew existed, much less visited.