Breaking Circuit Boundaries: The Surprising Power of Inter-Circuit Citations

What happens when federal appeals judges break out of their own circuit’s bubble? A closer look reveals a fascinating web of influence that could reshape the future of federal law

Out of over 3,200 federal appeals court opinions released between the beginning of November 2024 and January 17, 2025, only four cited cases from each of the other circuits. I will get to those four cases later in the post but first I’ll pose the question of why this is important or interesting at all.

Stare decisis comes in several forms. The most common form is vertical stare decisis. This is when a lower court is bound by decisions from a higher court. On the federal level this describes how federal courts of appeals and district courts are bound by decisions of the United States Supreme Court and district courts are also bound by decisions from courts of appeals within the same circuits. Then there is horizontal stare decisis. Each circuit has a different practice for how it treats previous decisions from within the same circuit, generally looking at these as persuasive but not binding decisions.

Another type are instances like the ones I focus on in this article where judges on courts of appeals cite decisions from different circuits. These inter-circuit citations are much less common than citations based on vertical stare decisis or even intracircuit horizontal citations.

A previous paper by Michael Solimine, William Landes, and Lawrence Lessig looked at judicial influence with some metrics based on inter-circuit citations in a 1998 paper. In general though, there has been little scholarly work examining this phenomenon, especially because there are no clear guidelines for when this practice (of inter-circuit citations) is appropriate.

This article looks at inward and outward inter-circuit citations to examine the amount of attention each circuit pays to other circuits and then to pinpoint the instances where these citations arise.

Findings

To run this analysis, I created a spreadsheet with each decision since the beginning of November 2024 that includes the majority authors along with the external circuits’ decisions cited in each decision if any.

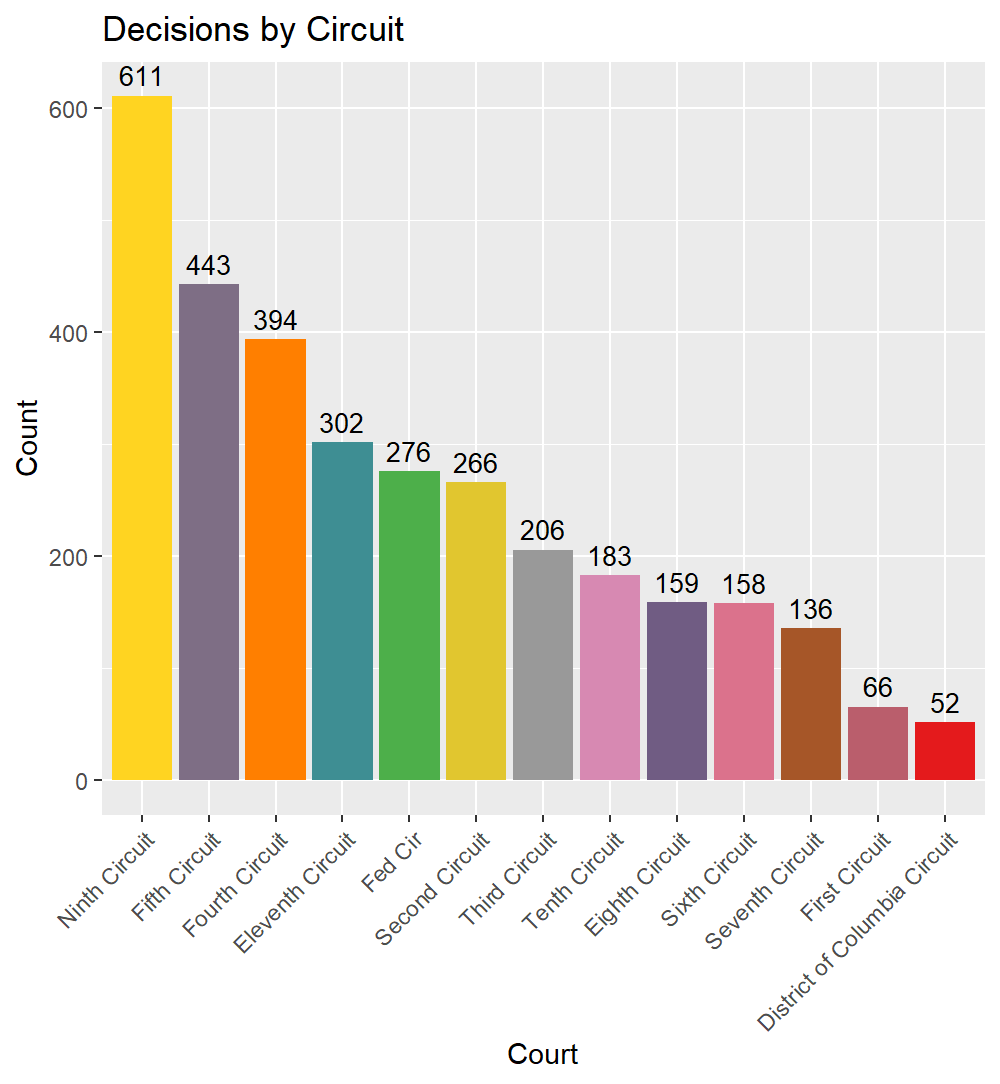

This showed that 774 of the decisions had at least one external circuit cited and more than half of the observations, 2,060 in all, were per curiam or unsigned. Below is the number of decisions per circuit which more or less parallels expectations with the circuits with the highest decision counts as the Ninth and Fifth and the fewest decisions coming from the DC and First Circuits.

Now to see the frequency of number of circuits cited, the following graph is a histogram capturing the 774 decisions citing an external circuit based on the number of circuits cited so, for example, a decision from the Fifth Circuit citing four decisions from the Sixth Circuit, three from the Seventh, and two from the Eighth would lead to an output of three because of the three circuits cited. I did not track the number of cites to specific external circuits within decisions and only coded if an external circuit’s decision was cited within the decision from a given observation.

Next a look at the frequency of inter-circuit citations based on the citing circuit so that each circuit on the graph shows the percentage of its decisions citing to at least one other circuit.

The First Circuit, a smaller circuit, is the heaviest citing circuit to other circuits while the subject matter specific Federal Circuit unsurprisingly has the lowest percentage of external citations along with the Fourth Circuit. The Ninth Circuit which is the largest geographic circuit with quite an established set of intracircuit precedent has nearly the lowest percentage of decisions with inter-circuit citations.

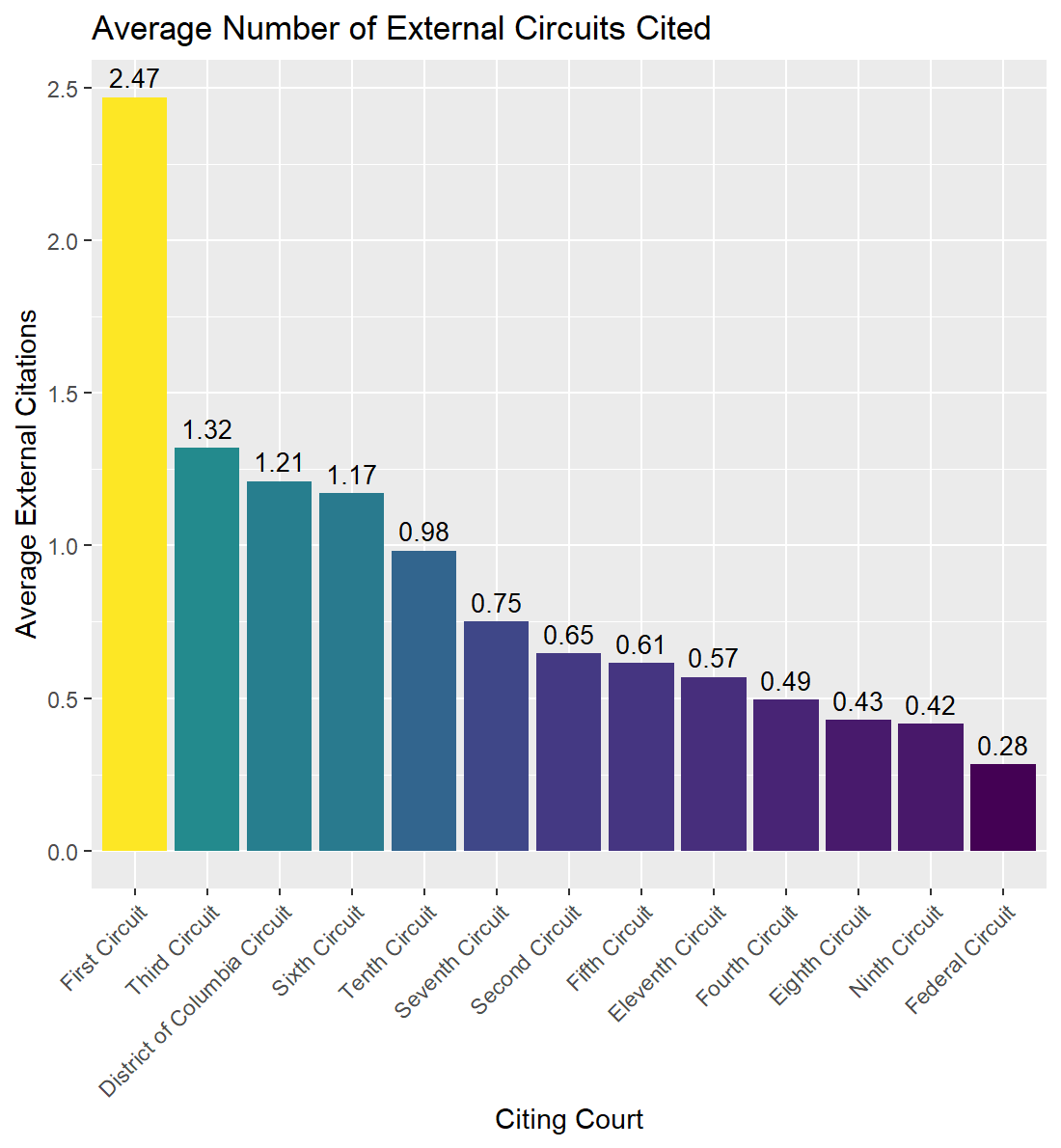

Looking at the average number of inter-circuit citations from each citing court per decision we see the following

The First Circuit also cites the most other circuits in its decisions based on the count of circuits cited and not only the binary of if a decision has inter-circuit citations or not. There is a big drop off to the other circuits and like the other graphs, Federal Circuit decisions also cite the fewest number of external circuits per decision.

To probe these data a bit deeper, the following table shows the citing court on the vertical axis and the cited court on the horizontal axis, so, for instance, a cell with two in it and with the Third Circuit on the vertical axis and the First Circuit on the horizontal axis means two Third Circuit decisions cited First Circuit decisions.

This shows us that First Circuit decisions cite Second Circuit decisions most often, Second Circuit decisions cite Ninth Circuit decisions most often, and so on.

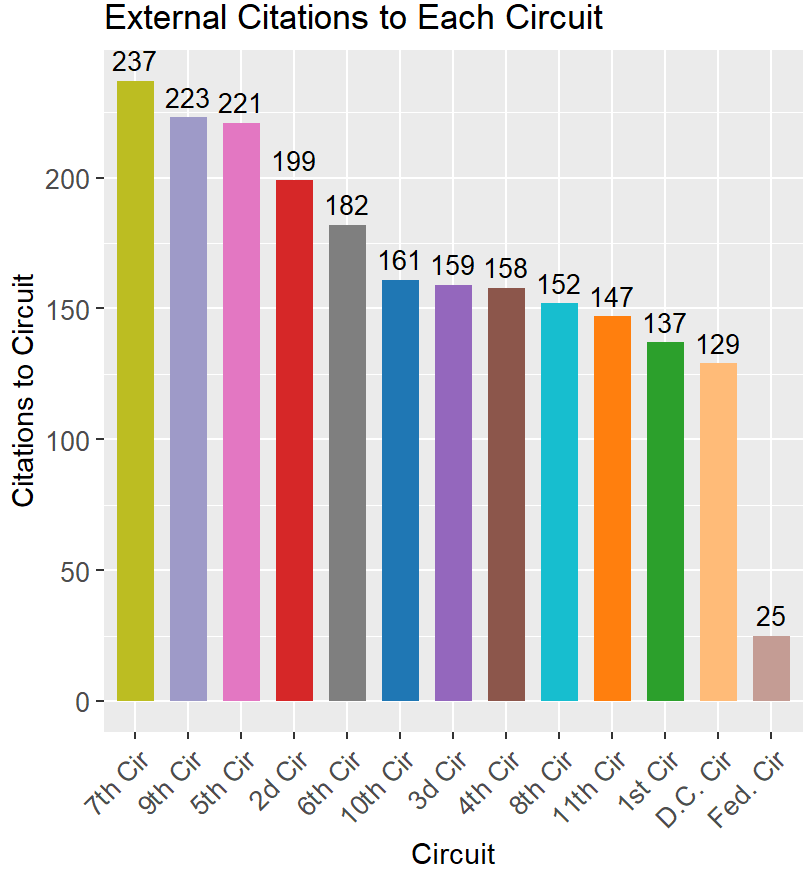

From the other direction, the circuits cited the most by other circuits’ decisions are shown below.

Like the graph of citing circuits, the Federal Circuit also has the lowest number of inter-circuit citations citing to it likely because it is subject matter specific. The DC and First Circuits which have light outputs relative to the other circuits also have lower internal citations than those to the other circuits. Interestingly, even though the Ninth Circuit puts out the most annual opinions, more decisions from other circuits cited Seventh Circuit decisions than decisions from any other circuit.

To shift the focus a bit, the next two graphs examine majority authors that have decisions citing the largest number of decisions from other circuits. The first graph tracks the absolute number of external citations from the majority authors with the most external citations within the dataset. The number in parentheses counts the number of signed majority opinions from these judges.

Third Circuit Judge Krause has the most inter-circuit citations by a six circuit count margin across nine opinions. Then Judge Sutton, Moore, Brennan, and Aframe all have 28 inter-circuit citations, but from varying numbers of their own opinions. To normalize these numbers, the next graph uses the same judges, but divides the external circuits cited by the number of decisions in parentheses to get a rate of inter-circuit citations per majority opinion.

Judges Menashi and Federico, have the highest rates of nine inter-circuit citations per decision followed by Judge Jordan with 7.33 inter-circuit citations per opinion. These high rates indicate heavy reliance on principles from other circuits’ decisions and perhaps a more open approach to the use of persuasive and not only binding precedent.

Finally, to dig in a bit deeper into two of the decisions citing each of the other 12 circuits’ decisions, here are a few points about each.

The first is the First Circuit’s per curiam decision in Kress Stores of P.R. v. Wal-Mart P.R., Inc.

The case centers on the procedural question of proper joinder and federal jurisdiction under CAFA, as well as substantive claims of unfair competition. The court ultimately found in favor of Costco and Walmart, emphasizing the lack of a duty, causation, and enforceable rights under the cited legal provisions. The dissent focuses on procedural fairness and the broader implications of jurisdiction and joinder decisions in similar cases.

Citations to decisions from other circuits were crucial in this case because they helped establish a broader, more consistent interpretation of legal principles, particularly regarding the procedural issues of severance and jurisdiction. By referencing decisions from different circuits, the court was able to demonstrate that its reasoning aligned with a nationwide understanding of similar legal issues, ensuring uniformity in the application of the law across jurisdictions. This also strengthened the credibility of its conclusions, especially when the case involved complex legal questions that had been addressed in varying ways by other courts.

The second is the Third Circuit’s decision by Judge Krause in United States v. McIntosh

The case involves the defendant McIntosh challenging the application of sentencing enhancements under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, specifically regarding whether his possession of a firearm was in connection with another felony offense and whether the firearm could be classified as capable of accepting a large capacity magazine. The court affirmed the application of the sentencing enhancements, ruling that the firearm in question met the definition of "semiautomatic firearm that is capable of accepting a large capacity magazine" and that McIntosh's conduct was tied to another felony offense, thereby justifying the enhancements. The court upheld the district court's sentence.

In this case, citations to decisions of other circuits are used to support the court's reasoning and to demonstrate how various appellate courts have interpreted similar issues under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines. These precedential decisions help establish that the interpretations of terms like "large capacity magazine" and "another felony offense" are consistent across circuits, reinforcing the validity of the sentencing enhancements applied in McIntosh's case. The citations also provide legal authority for deferring to the Sentencing Commission's commentary and its reasonable interpretations.

Conclusion

Inter-circuit citations serve a critical function in ensuring consistency and alignment of legal principles across federal circuits. The findings reveal that circuits use these citations in distinct ways, with some circuits—such as the First and Second—frequently citing decisions from other circuits to strengthen their arguments, often integrating persuasive precedent into their reasoning. This practice reflects a potential openness to broader interpretations and a desire for uniformity across the judiciary, particularly on complex or nuanced legal questions. In contrast, circuits like the Federal Circuit, with its subject-specific focus, are less likely to engage in inter-circuit citations, relying more on internal precedent.

The differential use of inter-circuit citations may indicate a strategic approach to building legal arguments, with certain circuits seeking to solidify the national consistency of their decisions. While some circuits embrace external precedents to bolster their positions, others may rely more heavily on intra-circuit precedents or limit external citations due to the specificity of their subject matter. This variation in citation practices raises important questions for future research, particularly regarding how these citation patterns affect legal coherence across circuits and the development of jurisprudence in areas with frequent inter-circuit conflicts. Further exploration could focus on how judges decide when to use external citations and how this impacts the consistency and predictability of federal law.

If you enjoyed reading this post please subscribe and share Legalytics with others. Also you can start a discussion by leaving a comment.

One explanation for the First Circuit use of other circuit precedents might be that its case load has been lighter than other circuits for many years and thus it lacks First Circuit precedent in areas that larger circuits have precedents. I would think that might be true for the Tenth Circuit (and perhaps others) as well, but I don't have as clear a grasp of the relative workloads.

I’m a bit confused about the first case cited: Kress v. Walmart … how does Costco fit in?