Chevron’s Swan Song: Loper Bright and the New Era of Judicial Oversight of Agency Actions

This article explores how the Supreme Court's Loper Bright v. Raimondo decision reshapes agency power, shifts judicial deference, and looks at what this means for future legal battles.

[First a note that it may be worth looking at my previous analysis of the TikTok oral arguments to see how it accurately predicted the case outcome and votes along with highlighting several aspects that factored into the Court’s decision along with the separate opinions.]

Now for the article…

From 1984 to 2024, judges examining agency interpretations of statutory language followed the following guidelines: “When a challenge to an agency construction of a statutory provision, fairly conceptualized, really centers on the wisdom of the agency's policy, rather than whether it is a reasonable choice within a gap left open by Congress, the challenge must fail. In such a case, federal judges — who have no constituency — have a duty to respect legitimate policy choices made by those who do. The responsibilities for assessing the wisdom of such policy choices and resolving the struggle between competing views of the public interest are not judicial ones: ‘Our Constitution vests such responsibilities in the political branches.’ TVA v. Hill, 437 U. S. 153, 195 (1978).” These are Justice Stevens’ words from the 1984 Supreme Court decision in Chevron v. NRDC. In 2024’s Loper Bright v. Raimondo, Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the Court’s majority: “Chevron was a judicial invention that required judges to disregard their statutory duties. And the only way to ‘ensure that the law will not merely change erratically, but will develop in a principled and intelligible fashion,’ Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U. S. 254, 265 (1986), is for us to leave Chevron behind.”

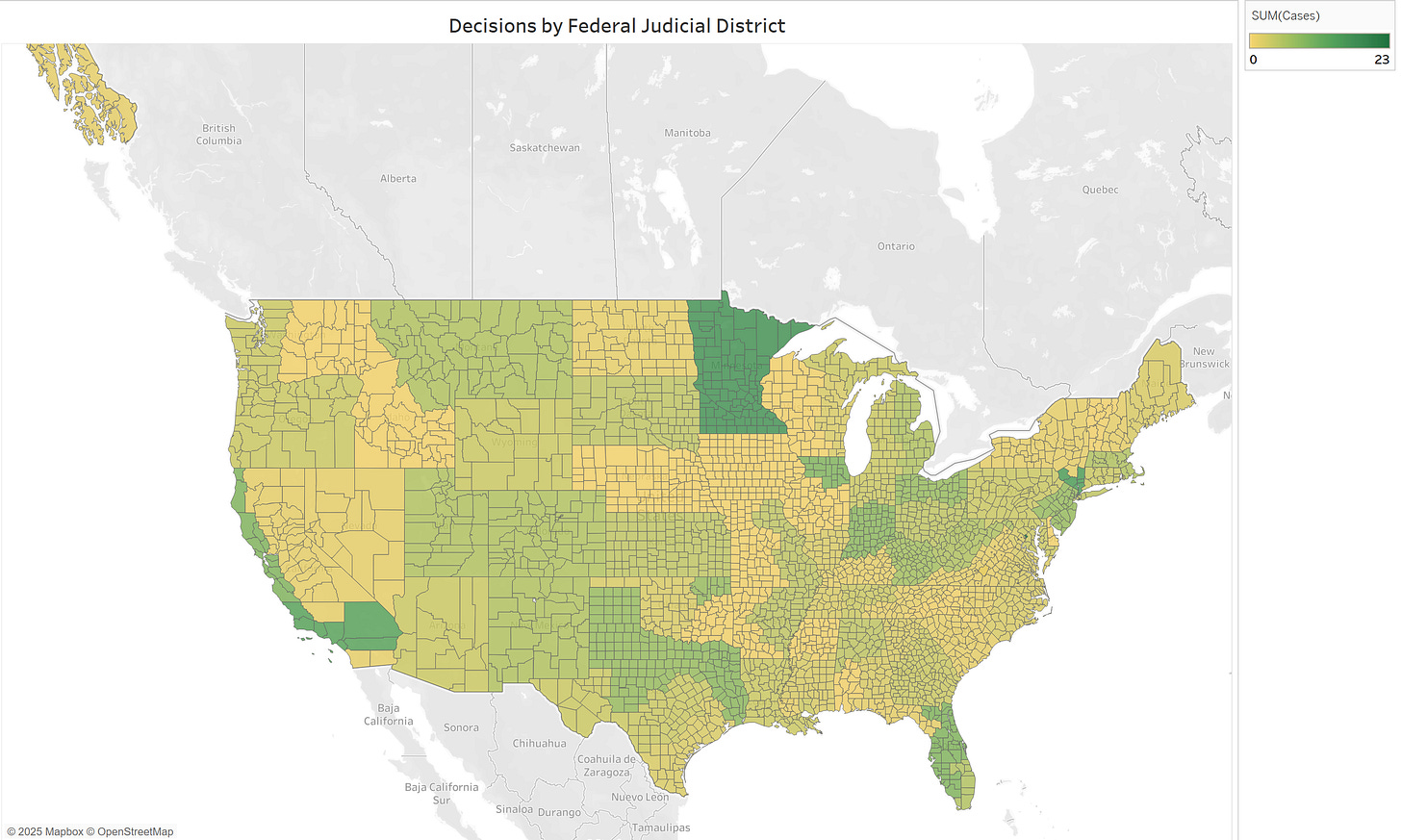

This overhaul drastically changed the legal landscape surrounding deference to agency interpretations of statutes and has left many question marks for attorneys and judges in this area on how to navigate in this new terrain. This article examines over 300 opinions from all types of courts, mostly federal with the exception of a few state court cases, that include citations to Loper Bright to try and get a sense of how courts will treat challenges to agency interpretations based on this recent shift in precedent.

Background

Judicial review of agency actions, grounded in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), presumes court oversight unless explicitly barred by statute or when actions are committed to agency discretion. In past, courts reviewed the administrative record to ensure agency decisions were not arbitrary, capricious, unconstitutional, procedurally deficient, or unsupported by evidence.

Under the "arbitrary and capricious" standard, courts would assess whether agencies provided rational explanations, considered relevant factors, and based decisions on evidence. While courts would defer to agency expertise, they would still try to maintain accountability while allowing policy flexibility.

In Loper Bright, the Supreme Court redefined the Chevron framework, particularly challenging its first presumption—that statutory ambiguities imply an implicit delegation of interpretive authority to agencies. The Court held that this presumption was inconsistent with APA, which asserts that courts, not agencies, should decide legal questions. The Court emphasized that while presumptions can be useful, the presumption under Chevron did not reflect reality because statutory ambiguities do not automatically grant interpretive power to agencies. Instead, courts are responsible for interpreting statutes, showing respect for the executive branch's views but not deferring to them. The majority argued that statutory meaning is fixed at the time of enactment, and courts are obligated to apply traditional tools of statutory construction to determine the best meaning, regardless of the complexity of the statute.

Courts, not agencies, are seen as the experts in interpreting statutes, and the legal nature of statutory interpretation does not change just because an agency is involved. The Court further rejected the idea that ambiguity in statutes automatically calls for agency expertise. Despite this, the Court noted that executive branch views may still be considered persuasive, referring to the Skidmore standard, which allows courts to give weight to agency interpretations under certain circumstances.

How has Loper Bright pervaded the landscape of agency/deference related litigation?

The data for analysis in this article is 313 court decisions examining Loper Bright and the new agency deference framework. The first 13 decisions were from the Supreme Court in the form of grants, vacates, and remands (GVRs) predicted on the Loper Bright decision (for example). The other Supreme Court opinion citing Loper was Corner Post which further shifted judicial review of agency actions.

The rest of the distribution of cases includes 18 from state courts including four from the District of Columbia Court of Appeals and two from the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

The district court map of decisions by case count is shown below with districts with the most cases in darker shades of green.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Legalytics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.