Clerks, Chambers, and Power: The Networks Behind the Court

This article shows Supreme Court clerkships now function less as prizes than as pipelines, channeling talent through tight networks into powerful firms and institutions.

Sarah Sloan, a Columbia Law graduate who clerked for Justices Kagan (and Stevens) {updated], told her law school’s alumni magazine that she never thought she’d wind up at the Court until she was encouraged by professors and circuit judges who knew the path well. Her experience underscores how personal recommendations and faculty pipelines remain decisive, even in an age of formal processes and online applications.

Reid Coleman’s path makes the machinery visible: an early White House stint, two high-signal appellate clerkships (Fifth and D.C. Circuits), faculty-backed clinics, and then the capstone year with Justice Thomas—followed by a landing at Kirkland & Ellis. It’s a case study in how modern pipelines actually run: mentors and repeat-player judges smooth the way, district and circuit feeders credential the résumé, and an elite firm scoops up the result. Texas Law’s climb in federal placements and its 40th Supreme Court clerk show the center of gravity widening beyond the usual Ivy duopoly, but the architecture remains the same—tight networks, long apprenticeships, and a hiring market that channels new Court alumni into a handful of powerful institutions poised to shape litigation for years.

The University of Virginia has celebrated its alumni who went from clerking to running state solicitor general offices, leading major law firms, and shaping national policy. One former Roberts clerk described it simply: “It’s not just a credential — it’s an entire professional universe.” That universe is why firms now pay signing bonuses of $450,000 to attract clerks fresh out of One First Street, a practice so entrenched that it has reshaped lateral hiring at the country’s most profitable law firms.

The exclusivity of the system has long been recognized by scholars. A 2020 article in the George Washington Law Review noted how Supreme Court clerkships “magnify inequality,” concentrating opportunity in a handful of schools and chambers while systematically excluding others. Princeton’s Jonathan Kastellec has gone further, documenting how former clerks themselves become gatekeepers, recommending and screening candidates in ways that reinforce existing hierarchies. The result is a cycle: the same institutions that dominate clerk hiring replicate their influence generation after generation.

All of this matters because clerkships are not just lines on a résumé. They are an early window into the Court’s culture, a credential that can tilt careers, and a network that reaches far into American law and politics. Taken together, the numbers show both continuity and change. From Justice Thomas’s long record beginning in 1991 to the newer chambers of Justices Barrett and Jackson, the clerkship market has retained its familiar concentration in a handful of schools and feeder judges. But the data also capture real shifts—longer timelines to the Court, new district-level pipelines, and widening gaps in cross-party hiring—that reveal how the clerkship system is not static but steadily hardening into more defined networks.

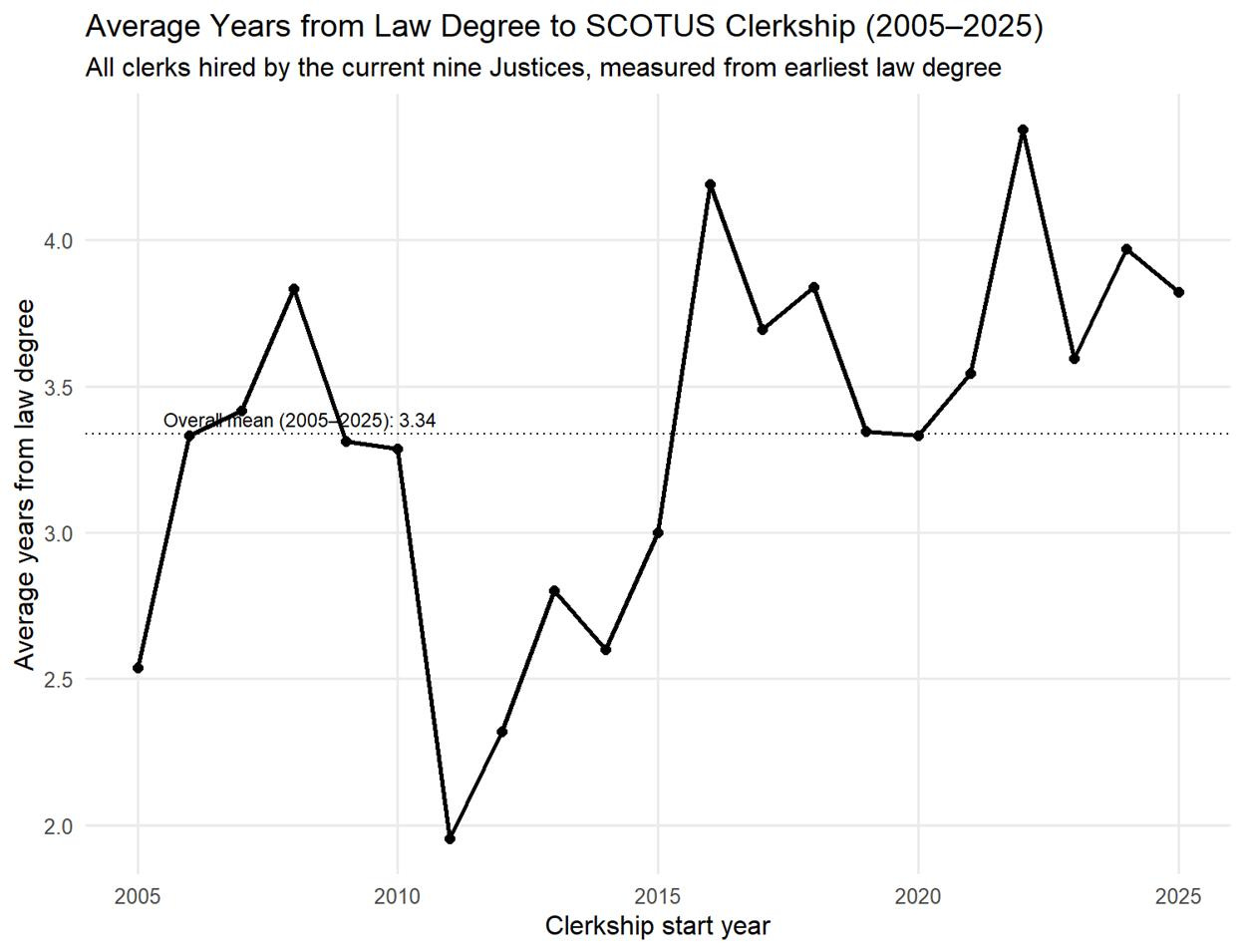

Time to the Court

How long does it take between graduating law school and a Supreme Court clerkship? The timeline has lengthened. In the mid-2000s, new Supreme Court clerks typically arrived about 2.5 years after law school; by the mid-2020s the average is nearer 3.8 years. The pattern reflects two shifts: candidates increasingly add a second clerkship or a year in the Solicitor General’s Office/DOJ before applying, and the feeder system rewards deeper résumés. Law firms then bid up the market for those veterans, reinforcing incentives to accrue experience before the Court.

Clerks are not assistants so much as extensions of the chambers’ work—screening petitions, drafting, and debating strategy—so it’s unsurprising that justices and feeders alike prize additional seasoning. Former clerks and recruiters describe a pipeline that has become more process-driven and competitive, with preparation starting early and routed through a small set of high-signal judges.