Disparate Ninth Circuit Takes on the Birthright Citizenship Order

Judges Gould and Bumatay come out on different sides of this issue. Who is right? Who is more consistent? The data paint the picture, but the truth is in the eye of the beholder.

In State of Washington, et al. v. Trump, et al., the Ninth Circuit reviewed the constitutionality of Executive Order No. 14160, issued by President Trump in January 2025. The Order attempted to deny U.S. birthright citizenship to children born on U.S. soil to parents who were either temporarily or unlawfully present in the country. The states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois, and Oregon challenged the Executive Order, arguing it violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Citizenship Clause. This marked “[the] first time that an appellate court has weighed in on the merits of Mr. Trump's attempt to end birthright citizenship for many children of undocumented immigrants by executive order.”

Judge Gould, writing for the court, held that the Executive Order was unconstitutional because it directly contradicted the plain language of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees citizenship to "all persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof." The majority opinion emphasized that the Citizenship Clause, as interpreted by United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), applies regardless of parental immigration status.

The panel affirmed a universal preliminary injunction issued by the district court, blocking enforcement of the Order. While the court dismissed the claims of individual plaintiffs (due to their inclusion in a pending class action), it upheld the states' standing and their likely success on the merits. Judge Bumatay dissented in part, arguing that the states lacked standing and that the court had overstepped its jurisdiction.

Judge Gould’s opinion in this case exhibits several identifiable jurisprudential themes and methods.

Textual Fidelity to the Constitution

Judge Gould grounds his opinion in the unambiguous language of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause, emphasizing that its plain text guarantees birthright citizenship to all persons born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction. He decisively rejects efforts to reinterpret or limit this language through executive policy or political framing. For Gould, constitutional text is not malleable in the face of administrative reimagining: “We conclude that the Executive Order is invalid because it contradicts the plain language of the Fourteenth Amendment’s grant of citizenship.” This fidelity to the written Constitution forms the cornerstone of his legal reasoning throughout the opinion.

Historical Precedent and Original Understanding

In interpreting the Citizenship Clause, Gould relies heavily on the Supreme Court’s longstanding precedent in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). He meticulously traces the legal and historical lineage of birthright citizenship, framing it as a doctrine solidified by both judicial authority and the original intent behind the Fourteenth Amendment. Importantly, Gould connects this tradition to the Amendment’s repudiation of Dred Scott, underscoring that the Citizenship Clause was meant to permanently close the door on racialized exclusions from citizenship. As he puts it, “The Supreme Court canvassed English common law, early American decisions... and then held that the Citizenship Clause stands for ‘the fundamental rule of citizenship by birth...’”

Limits on Executive Authority

A recurring theme in Gould’s jurisprudence—fully on display here—is the rejection of executive authority to reinterpret constitutional guarantees. The President, in his view, possesses no Article II power to redefine rights enshrined in the Constitution or to override settled judicial interpretations. Gould is clear that constitutional change cannot occur through unilateral executive will. As he writes, “The President was not granted... the power to modify or change any clause of the United States Constitution.” This line encapsulates his broader constitutional philosophy: the executive is bound by law, not a reviser of it.

Judicial Review and Equitable Remedies

Gould defends the district court’s decision to issue a universal preliminary injunction against enforcement of the Executive Order, finding that such relief was necessary to afford meaningful protection to the plaintiff states and the individuals affected. While he stops short of endorsing nationwide injunctions as a general rule, he endorses their use when tailored to the constitutional harm at issue. His reasoning is pragmatic and case-specific, echoing his broader view that remedies must track the scope of the injury. “We conclude that the district court did not abuse its discretion in issuing a universal preliminary injunction,” he affirms, emphasizing the centrality of judicial discretion in constitutional equity.

Commitment to Structural Constitutionalism

Underlying Gould’s opinion is a deep commitment to the principles of separation of powers and constitutional design. He reads the Executive Order as an encroachment on the Constitution itself, an effort by the executive branch to achieve indirectly what it cannot do directly. His concern is not only with the immediate effects of the order, but with the institutional logic it threatens. Gould’s skepticism is clear: “Perhaps the Executive Branch, recognizing that it could not change the Constitution, phrased its Executive Order in terms of a strained... interpretation...” The statement reflects his broader apprehension about executive overreach and underscores his view that the judiciary serves as a bulwark against such constitutional distortions.

Judge Gould’s ruling in Trump v. Washington underscores his jurisprudential consistency in textual adherence, fidelity to historical precedent, and robust defense of constitutional limits on executive authority.

Prior Cases

Textual Anchoring with Structural Sensitivity

Across his judicial record, Judge Gould exhibits a disciplined, text-first methodology, especially in constitutional and statutory cases. He begins with the words of the law and interprets them within their ordinary meaning, yet consistently situates those words within the broader framework of the legal or constitutional scheme in which they operate. This combination of textual clarity and structural sensitivity is evident in cases like Bayliss v. Barnhart, where he affirms administrative discretion but anchors his reasoning in evidentiary consistency across the record. Similarly, in Safe Air for Everyone v. Meyer, Gould offers a narrow reading of the term “solid waste” under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, relying on common usage and regulatory intent. Even so, he frames that analysis within a practical understanding of environmental reuse and policy design, showing how textual precision and systemic functionality coexist in his jurisprudence.

Institutional Restraint with Assertive Constitutional Adjudication

Judge Gould’s decisions reflect a measured deference to institutional actors—whether agencies or lower courts—until constitutional stakes compel judicial engagement. He generally respects the boundaries of administrative governance, but when fundamental rights or structural constitutional norms are threatened, he is willing to intervene assertively. In Menotti v. City of Seattle, for instance, Gould upholds the city's security measures around protest zones but carefully articulates the boundaries of expressive conduct protected under the First Amendment. Likewise, in Kootenai Tribe of Idaho v. Veneman, he invalidates a nationwide injunction blocking a forest rule, respecting agency discretion while insisting on rigorous compliance with NEPA's procedural demands. These decisions typify a pattern in which Gould’s deference yields to constitutional stewardship—he guards procedural and participatory rights with particular care when they come under strain from executive or administrative power.

Procedural Integrity and Evidentiary Grounding

Gould’s jurisprudence is marked by a steadfast commitment to procedural rigor. His rulings often hinge on the integrity of the administrative or evidentiary record, reflecting a deep belief that process is not a formality but a substantive element of justice. In Bayliss, he upholds the denial of benefits by closely examining the ALJ’s record-based rejection of conflicting medical opinions. Likewise, in Shrestha v. Holder, Gould affirms an immigration tribunal’s credibility findings but underscores that such assessments must be individualized and holistic under the REAL ID Act. For Gould, procedural fidelity is not a matter of box-checking; it is essential to fair adjudication across legal contexts, whether in administrative review, immigration proceedings, or statutory enforcement.

Doctrinal Stability Over Innovation

When interpreting longstanding doctrines—particularly in criminal and immigration law—Gould tends toward judicial modesty. His opinions reveal a preference for doctrinal continuity over creative or aggressive innovation. In United States v. Pacheco-Zepeda, for example, he upholds a sentencing enhancement under 8 U.S.C. § 1326(b)(2), explicitly reaffirming the controversial Almendarez-Torres precedent even amid post-Apprendi skepticism. Similarly, in Paladin Associates v. Montana Power, he applies the antitrust injury doctrine with fidelity to established commercial expectations, avoiding any doctrinal expansion. These cases show a judge who respects precedent and is wary of shifting legal standards absent clear guidance from Congress or the Supreme Court.

Pragmatic Environmental Federalism

In his environmental rulings, Gould strikes a pragmatic balance between federal regulatory objectives and local governance. He respects the technical fact-finding and discretionary space afforded to agencies, yet demands procedural compliance and analytical transparency. In Safe Air and Kootenai, he enforces environmental rules not from an ideological standpoint but from a structurally grounded perspective, attentive to both regulatory goals and practical implementation. His opinions reflect neither sweeping pro-regulatory nor anti-regulatory instincts, but rather a context-specific commitment to coherent environmental oversight within federalist constraints.

Tone: Measured, Analytical, Occasionally Cautious

Gould’s judicial writing is typically marked by its deliberative, analytical tone. He favors statutory and constitutional parsing over rhetorical flourish and often opts for cautious language when constitutional and policy considerations intersect. His style avoids speculative theorizing, preferring instead to reason from principle and precedent. While many of his opinions are understated in tone, they close with strong normative affirmations when constitutional limits are at stake—as in Trump v. Washington, where the opinion culminates in a clear defense of rule-of-law commitments and judicial review. Throughout his corpus, Gould demonstrates a preference for logic over passion and for institutional continuity over improvisational flair.

Judge Gould’s Jurisprudence in Trump v. Washington in Context

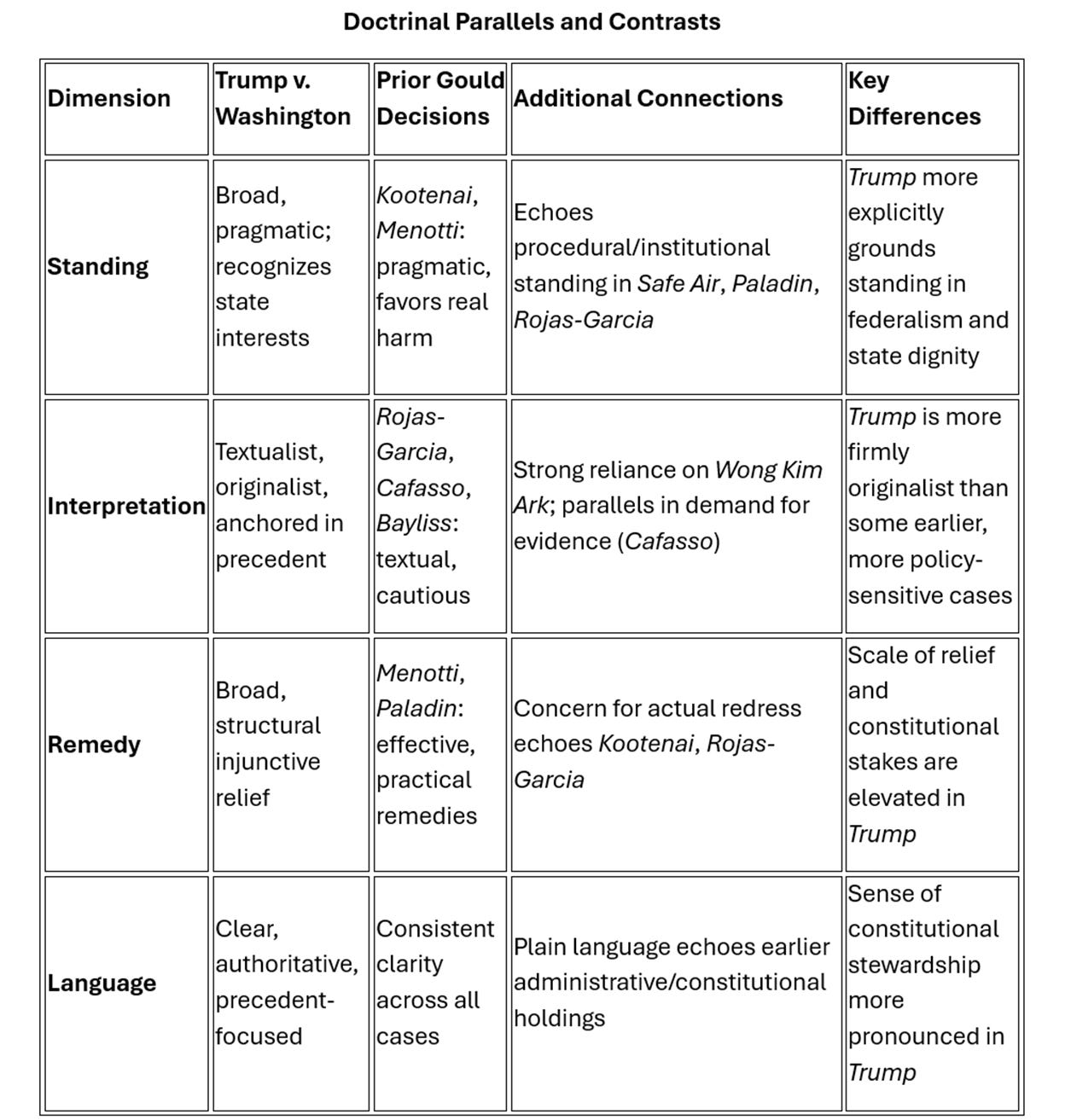

Doctrinal Foundations and Standing

In Trump v. Washington, Judge Gould’s approach to standing reflects a jurisprudence developed across two decades on the Ninth Circuit, where he has repeatedly privileged concrete harm and access to the courts over rigid formalism. This pragmatism is apparent in earlier cases such as Menotti v. City of Seattle and Kootenai Tribe of Idaho v. Veneman, where Gould found standing for parties alleging institutional, environmental, or collective harms. The reasoning in Trump v. Washington—accepting state “quasi-sovereign” interests, such as the threatened disruption to health systems and state budgets, as a sufficient basis for standing—reprises the flexible, real-world analysis seen in those earlier decisions.

Yet there are nuances that distinguish the Trump opinion. While cases like Kootenai and Safe Air for Everyone centered on environmental or procedural injuries, Trump marks an evolution by explicitly recognizing state dignity and federalism as components of the standing inquiry. Where previous opinions leaned on individualized or organizational interests, Trump more directly affirms the role of states as guardians of their residents’ constitutional rights, reflecting a subtle but important shift in Gould’s understanding of justiciability in the federal courts.

Constitutional and Statutory Interpretation

Gould’s interpretive method in Trump is marked by a commitment to constitutional text, historical understanding, and fidelity to Supreme Court precedent—an approach consistent with his readings in cases like Rojas-Garcia v. Ashcroft and Cafasso v. General Dynamics. In those opinions, Gould’s writing eschews policy-driven analysis in favor of textual clarity and precedent, and in Trump he deploys the same analytic rigor, grounding his reading of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause in the history and authority of United States v. Wong Kim Ark.

Language from Cafasso and Bayliss v. Barnhart reveals a consistent thread: Gould’s skepticism of claims or interpretations not anchored in the statutory or constitutional text. In Trump, this skepticism manifests as a refusal to countenance administrative attempts to reinterpret birthright citizenship in ways that depart from established law. This is, perhaps, an even more pronounced textualism and originalism than one finds in his more pragmatic or policy-sensitive administrative law opinions such as Safe Air or Lands Council—a response, perhaps, to the unique constitutional stakes of the case.

Remedies and Judicial Role

The remedy crafted in Trump v. Washington—upholding comprehensive injunctive relief—draws on a jurisprudential philosophy evident in cases like Menotti and Paladin Associates. Gould consistently maintains that judicial remedies must be real and effective, not simply symbolic or technical. In Menotti, the response to constitutional violations during public protest was both thorough and attuned to the scope of the injury. Similarly, Trump reflects a judicial unwillingness to allow core constitutional rights to be undermined by executive action, even in the face of complex policy arguments.

What sets Trump apart is the scale and visibility of the relief. While Gould has previously endorsed robust remedies in contexts such as NEPA enforcement (Kootenai) or immigration due process (Rojas-Garcia), Trump moves into the heart of constitutional structure, insisting that the courts must serve as a bulwark when foundational guarantees—such as birthright citizenship—are threatened by administrative reinterpretation.

Language and Doctrinal Evolution

Comparing Gould’s language across these cases reveals both continuity and evolution. The plainness and authority with which he invokes precedent in Trump—for example, “the Fourteenth Amendment’s command is settled and beyond administrative dispute”—recalls the clarity with which he has dispatched procedural and statutory claims in Rojas-Garcia and Cafasso. Yet there is a heightened sense of constitutional stewardship in Trump, perhaps a reflection of the moment and the magnitude of the right at stake, that marks an evolution from his environmental and administrative law work.

Trump v. Washington both extends and consolidates core elements of Judge Gould’s jurisprudence, reaffirming his commitment to access, textual fidelity, and meaningful remedies, while also responding to the unique constitutional challenges of the moment with a pronounced emphasis on federalism and the enduring power of the Fourteenth Amendment.

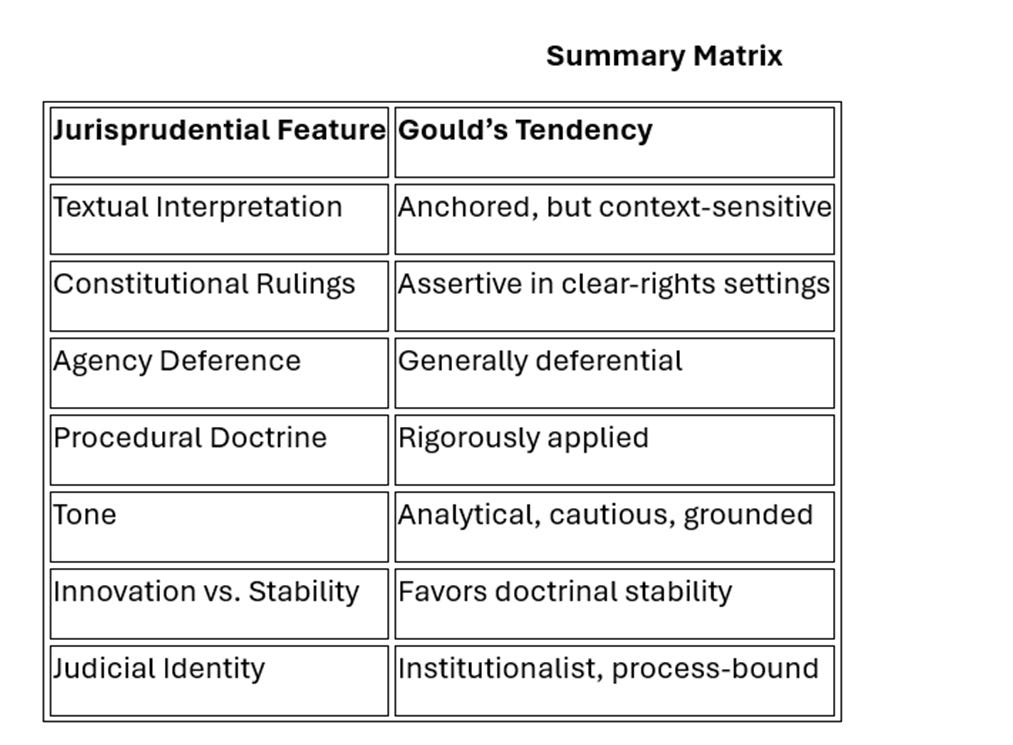

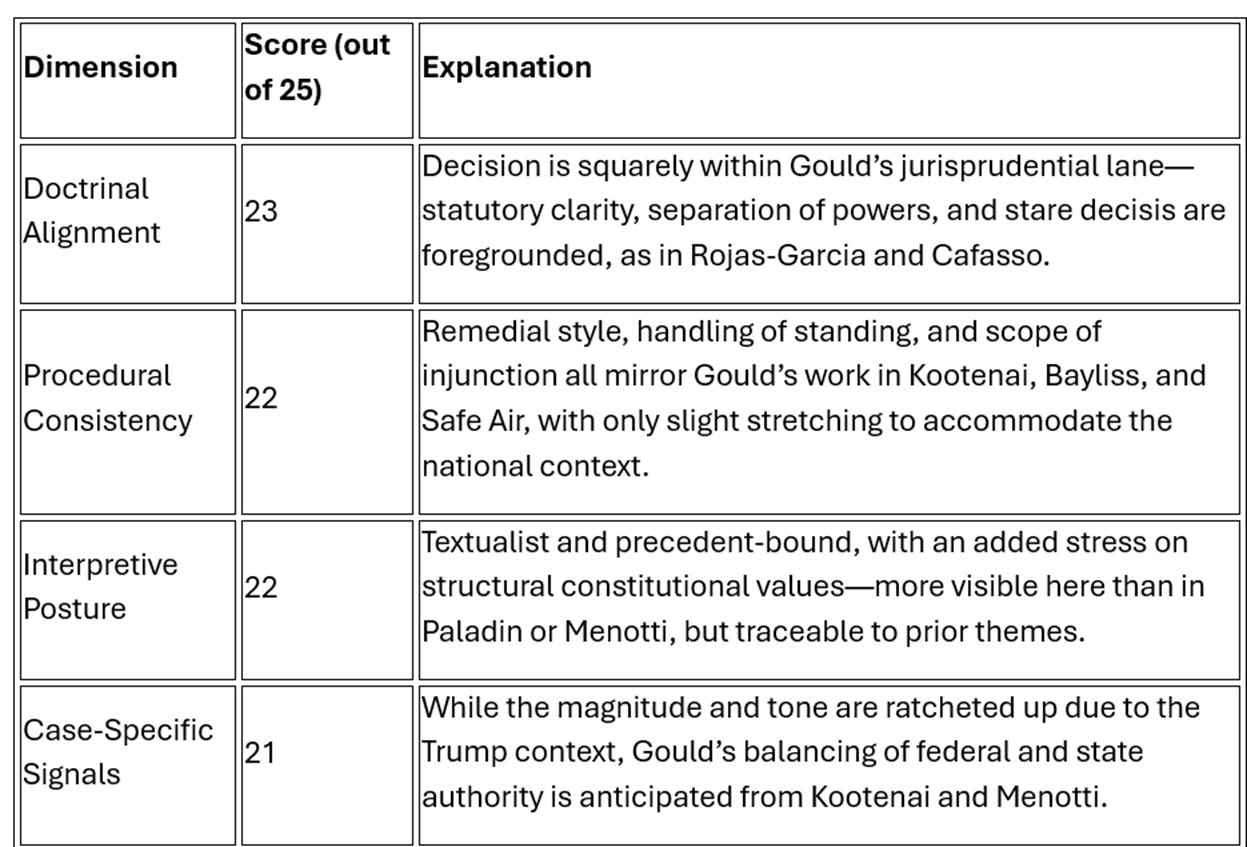

The methodology I use to measure predictability below is similar to that which I used in my previous post on multiple district court judges’ decisions. Judge Gould demonstrates high predictability scoring 88 on a predictability scale of 0-100, with his Trump v. Washington decision tightly tracking his established doctrinal and procedural approaches, as evidenced across the ten-case sample. His consistent textualism, clear procedural discipline, and fidelity to precedent anchor his ruling—though the case’s historic scale pushes his interpretive posture and signals slightly into more assertive terrain.

Takeaway: Predictability, Power, and Judicial Character in the Trump v. Washington Context

The importance of Judge Gould’s consistent, methodical approach comes into sharp relief in the context of Trump v. Washington. Here, the stakes are not only legal but existential—state autonomy, federal reach, and the outer boundaries of executive action are all on the table. The fact that Gould’s decision can be so closely mapped to his jurisprudence in earlier, less politically charged domains (federal environmental, administrative, and immigration law) is not a mere historical curiosity, it seems intentional.

Why does this matter for the Trump case?

It provides litigants, government actors, and the public with a clear “grammar” for understanding both the outcome and the legal route by which it was reached. In moments when executive power is expanding or being contested, a judge’s capacity for doctrinal and procedural predictability acts as a check against both overreach and ad hoc decision-making. Gould’s ruling signals to the parties—and to the watching nation—that the judiciary, even under stress, is anchored in precedent and method, not headlines.

Extrapolating to Other Judges and Future Litigation:

Gould’s approach offers a template for evaluating judicial behavior in similar flashpoint cases—whether they arise from Trump-era policies or from future moments of executive assertion. For judges with similarly high procedural and doctrinal consistency one can reasonably expect that challenges to federal executive action will be assessed with a clear eye to precedent, text, and process, and that the scope of remedies will track established judicial practice rather than personal or political preference.

For judges whose records show greater case-specific variance or a more experimental interpretive style, the outcome may be less predictable—remedies may be broader or narrower, and the tone or scope of judicial engagement may shift more dramatically in response to the political moment. But even here, using Gould as a benchmark allows scholars and practitioners to measure just how far a given decision veers from established patterns and, crucially, why.

In the ongoing legal battles over Trump-era executive actions, knowing the type of judge on the case is as important as knowing the legal merits. Gould’s predictability in Trump v. Washington underscores that, in times of national controversy, the judiciary’s most vital contribution may be the consistency—and transparency—of its reasoning, not the ideology of its result.

This context provides both a reassurance and a warning: predictability fosters trust in the legal system, but every departure from a judge’s established path will be all the more visible, and all the more consequential, when the stakes are this high.

The Dissent of Judge Bumatay: A Focus on Judicial Modesty and the Separation of Powers

Judge Bumatay’s partial concurrence and dissent in the Washington v. Trump birthright citizenship litigation does not simply dispute the merits. Instead, he sharply reframes the case as a test of judicial self-restraint and fidelity to the limits of Article III, offering a meditation on the dangers of overreach even in the face of intense policy controversy.

The Stakes and the Court’s Role

Bumatay begins with an acknowledgement of the emotional and political charge: “Fewer questions could be more important than deciding who is entitled to American citizenship.” He openly concedes that “citizenship in our country is worth fighting for.” Yet, he pivots quickly to the idea that the role of the judiciary is not to answer every significant or contentious question: “No matter how significant the question or how high the stakes…we must adhere to the confines of ‘the judicial Power.’” Exceeding those limits—even in pursuit of justice—he warns, “violates the Constitution.”

Judicial Power: Separation of Powers and Historical Perspective

Drawing on the lessons of the Founding era, Bumatay emphasizes that “concentrating too much authority in only a few hands corrupts and threatens our freedoms.” The heart of his argument is that the federal judiciary, like the other branches, is bounded: “A vital separation-of-powers limit on the judiciary is that we may only grant party-specific relief.” For Bumatay, universal injunctions are a recent, dangerous innovation—“runaway universal injunctions conflict with the judicial role—encouraging federal courts to ‘act more like a legislature.’”

He leans on the Supreme Court’s recent pronouncement in Trump v. CASA: “universal injunctions ‘lack a historical pedigree’ and ‘fall outside the bounds of a federal court’s equitable authority under the Judiciary Act.’” Thus, only when “it would be all but impossible to devise relief that reaches only the plaintiffs” may a broader remedy issue, and such cases are “by far the exception.”

Standing as a Double Check

Judge Bumatay’s dissent is as much about standing as it is about injunctive scope. He describes standing as “another separation-of-powers mechanism to guard against judicial overreach,” one that “keeps courts in their place: deciding only concrete disputes between an injured plaintiff and a defendant according to the law.” If courts loosen standing while tightening injunctive relief (or vice versa), they merely “push the air to the other end” of the balloon—resulting in an “inflated power for the judiciary.”

This leads to Bumatay’s main critique of the majority: that the states do not have standing because their alleged fiscal injuries are “too speculative and contingent at this stage to constitute injuries in fact.” Even if the executive order eventually has downstream financial effects on states’ Medicaid or CHIP reimbursements, such injuries depend on “contingent future events that may not occur as anticipated, or indeed may not occur at all.” He describes the chain of causation as “riddled with contingencies and speculation.”

Third-Party and Parens Patriae Limits

Bumatay is particularly concerned about states “artfully pleading” their way around Article III and parens patriae limitations by recasting the rights of their citizens as fiscal harms. He reiterates, “it’s blackletter law that ‘[a] State does not have standing as parens patriae to bring an action against the Federal Government.’” (Haaland v. Brackeen). The dissent’s tone is wary: “Like other parties, States must show a cognizable harm to themselves—not just their residents—before invoking federal court jurisdiction to challenge federal government policy.”

On Self-Inflicted Injuries and Judicial Restraint

Even where the states’ budgets are impacted, Bumatay finds the harm “self-inflicted”—if Washington chooses to provide Medicaid to children who are ineligible for federal reimbursement, that is “Washington’s alone” to bear. “No State can be heard to complain about damage inflicted by its own hand.”

Bumatay consistently invokes Supreme Court authority to support these limits: “Plaintiffs cannot rely on speculation about ‘the unfettered choices made by independent actors not before the courts’” (Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l), and “federal courts would become a forum for any parties to air generalized grievances” if such speculative injuries sufficed.

On the Merits: No Opinion

Because he finds standing lacking, Bumatay deliberately declines to reach the merits of the constitutional question or the scope of the injunction. “Absent a party with Article III standing, it’s premature to address the merits of the citizenship question or the scope of the injunction.”

Key Elements of Judge Bumatay’s Jurisprudence in This Dissent

Article III Rigor and Judicial Restraint

At the core of Judge Bumatay’s dissent is a sustained insistence that the judiciary remain within the bounds of its constitutional authority. He roots his analysis in Article III's strict limitations, warning against the temptation for courts to resolve pressing national controversies by extending their jurisdiction beyond what the Constitution allows. For Bumatay, the separation of powers is not merely a structural feature—it is a safeguard against judicial overreach. He argues forcefully that courts “must adhere to the confines of ‘the judicial Power,’” and that to exceed those confines, even for causes that seem morally urgent or politically divisive, is itself a constitutional violation. The judiciary, in his view, is not empowered to act as a “roving commission” to arbitrate broad social conflicts; its role is to adjudicate concrete disputes between parties.

Skepticism Toward Universal Injunctive Relief

Judge Bumatay expresses particular concern about the increasingly common use of universal—or nationwide—injunctions by federal courts. He challenges both their historical legitimacy and their legal justification, noting that such sweeping relief “lacks a historical pedigree” and “falls outside the bounds of a federal court’s equitable authority.” In his dissent, he carefully distinguishes between what a court may grant and what it should grant, emphasizing that equitable relief broader than necessary to redress the plaintiffs’ injuries is permissible only in the rarest of circumstances. For Bumatay, equitable power is not a license for judicial maximalism. Rather, he suggests, “equity sometimes demands that courts grant less than complete relief,” especially when narrower remedies suffice.

Standing and the Limits of Judicial Access

A central pillar of Bumatay’s dissent is his strict application of standing doctrine. He insists that parties must demonstrate their own concrete injuries, and he challenges attempts to stretch standing principles to permit third-party or derivative claims. His opinion reiterates that “a party must assert his own legal rights and interests” and critiques the notion that states can sue the federal government under a generalized parens patriae theory. Notably, he employs a vivid analogy to warn against manipulating doctrine to suit political exigencies: “We can’t tighten one [doctrine] but loosen the other. That would be like squeezing one end of a balloon—it just pushes all the air to the other end.” For Bumatay, such doctrinal balancing is not a game of counterweights but a matter of constitutional integrity.

Concrete Injury and the Problem of Speculation

The dissent places significant weight on the requirement that plaintiffs demonstrate not just harm, but non-speculative harm. Bumatay is sharply critical of the majority’s willingness to credit theories of standing based on projected downstream effects, indirect costs, or hypothetical future behaviors. He characterizes the states’ theory of injury as speculative on two fronts: first, because it relies on uncertain predictions about the implementation of the Executive Order; and second, because it presumes independent third-party reactions to federal policy. In his view, this kind of conjectural harm is not sufficient to invoke federal jurisdiction. Courts, he maintains, are not authorized to decide cases on “what-ifs.”

Caution in the Face of Political Disputes

Perhaps most fundamentally, Judge Bumatay’s dissent is a plea for judicial humility. He does not deny the constitutional stakes of the case, nor does he diminish the importance of the underlying issues. Rather, he insists that constitutional adjudication must be grounded in restraint, patience, and respect for the separation of powers. Courts, in his view, should “wait until the federal government provides its plans before acting.” His opinion is wary of open-ended judicial engagement in policy arenas—especially when the claims before the court rest on uncertain futures or abstract projections. Bumatay is not unconcerned with constitutional rights, but he argues that their vindication must come through channels that preserve the judiciary’s limited and defined role in the constitutional order.

A Judicial Philosophy of Caution and Containment

In Trump v. Washington, Judge Bumatay’s dissent presents a tightly disciplined account of what courts can—and cannot—do under the Constitution. It is a defense not of executive power per se, but of judicial restraint in the face of political urgency. His framework privileges doctrinal containment over judicial experimentation, and it expresses deep skepticism toward remedies and standing theories that depart from historical practice or constitutional text. In this case, it seems that for Bumatay, the judiciary’s legitimacy depends on its refusal to exceed its charter—no matter the stakes. In this, his dissent serves both as a jurisprudential counterpoint to the majority and as a broader warning about the cost of crossing constitutional lines, even for causes that courts may find sympathetic.

Judge Bumatay’s dissent is a map of modern judicial skepticism—insisting that even constitutional showdowns like birthright citizenship must proceed “in manageable proportions,” with concrete injuries, and strictly within the judicial role as defined by Article III. His opinion is less about whether the policy is wise, and more about the guardrails that keep courts from acting “more like a legislature.”

Bumatay: Jurisprudential Style & Patterns

Textual Fidelity and Skepticism Toward Legislative Purpose

Judge Bumatay's judicial writing is consistently defined by rigorous textualism. His interpretive method resists judicial innovation, preferring a literal application of statutory and constitutional text. Bumatay warns against allowing legislative purpose, policy consequences, or abstract goals to override the precise language of enacted laws. This theme appears prominently in his dissent in Center for Investigative Reporting v. DOJ, where he rejected an “anti-entrenchment” reading of FOIA in favor of a strict construction of a later-enacted appropriations bar. Likewise, in Chicken Ranch Rancheria v. California, he parsed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) to determine that its list of negotiable compact topics was indeed exhaustive—yet cautioned that violating the list was only evidentiary, not dispositive, of bad faith. He favored remand for a neutral statutory test rather than reliance on legislative history or generalized aims. This insistence on statutory parsing over purpose-driven reasoning also framed his partial dissent in Solar Energy Industries Ass’n v. FERC, where he questioned the use of Chevron deference and challenged NEPA standing.

Anti-Entrenchment and Legislative Supremacy

Bumatay regularly invokes constitutional principles of non-entrenchment, holding that no Congress can bind its successors through procedural devices like “magic words” rules. In CIR v. DOJ, he asserted that a later statute barring FOIA disclosure must prevail over an earlier process-laden transparency law (the OPEN FOIA Act), even though the later law omitted a formal citation requirement. His citations to Chief Justice Marshall and Justice Scalia underscore his belief in legislative supremacy as a cornerstone of democratic governance. In his view, courts must respect the textual hierarchy of statutes, not superimpose judicial preferences for transparency or regulatory clarity where the law is unambiguous.

Formal Doctrinal Minimalism and Institutional Modesty

A hallmark of Bumatay’s jurisprudence is his refusal to innovate or expand doctrine without clear textual grounding. Whether addressing Second Amendment rights in Duncan v. Bonta, where he rejected balancing tests in favor of historical tradition, or voting claims in Mi Familia Vota v. Fontes, where he declined to infer standing from policy-oriented legislative findings, Bumatay maintains a minimalist stance. In his jurisprudence, courts do not exist to optimize policy; they exist to interpret and apply law. This deference to the political branches is not passive, but structural: it is the very definition of judicial constraint.

Structural Constitutionalism and Limits on Government Power

Bumatay frequently foregrounds federalism, separation of powers, and the constitutional design in his opinions. In Chicken Ranch Rancheria, he objected to the majority’s reliance on legislative objectives to override the textual bounds of IGRA, warning that such reasoning risks state overreach and infringes on tribal sovereignty. In California Restaurant Ass’n v. Berkeley, which he authored, Bumatay struck down a municipal ordinance banning natural gas hookups, holding it preempted by federal energy law. These cases reflect his broader view that structure is not theoretical—it is protective. Judicial fidelity to structure constrains both state and federal power, preserving individual and institutional liberty.

Procedural Discipline Anchored in Statutory Commands

While Bumatay values process and record-based adjudication, his procedural analysis always remains textually bounded. In In re Facebook, Inc. Sec. Litig., his dissent focused on statutory elements of loss causation under securities law, resisting any move toward factual speculation or plausibility thresholds unmoored from statute. Similarly, in Betschart v. Oregon, he insisted that habeas relief hinges on the strict application of procedural defaults as outlined by statute, not equity or policy goals. For Bumatay, process matters only insofar as it is legislated. He will not extend doctrines or rules beyond what the law demands.

Tone: Assertive, Formal, and Anchored in Method

Bumatay’s judicial voice, especially in dissent, is direct, formal, and often critical of the majority’s interpretive philosophy. He warns frequently of “judicial amendments” and cautions against judges who “divine” congressional purpose at the expense of clear text. His prose draws heavily on Supreme Court precedent, especially the writings of Justices Scalia and Thomas, as well as textualist scholarship. Though his tone can be sharp, it is grounded in method, not ideology. He rejects balancing tests, rejects speculation, and rejects results-driven reasoning—preferring instead to build each opinion around the scaffolding of constitutional and statutory form.

Bumatay’s opinions reflect a high-contrast textualist philosophy—he is resolutely anti-purposivist, defends congressional flexibility, and resists judicial expansion or contraction of doctrine. His dissents often serve as line-by-line critiques of any move away from statutory text, with pointed warnings about judicial overreach, legislative entrenchment, or “policy-driven” reasoning.

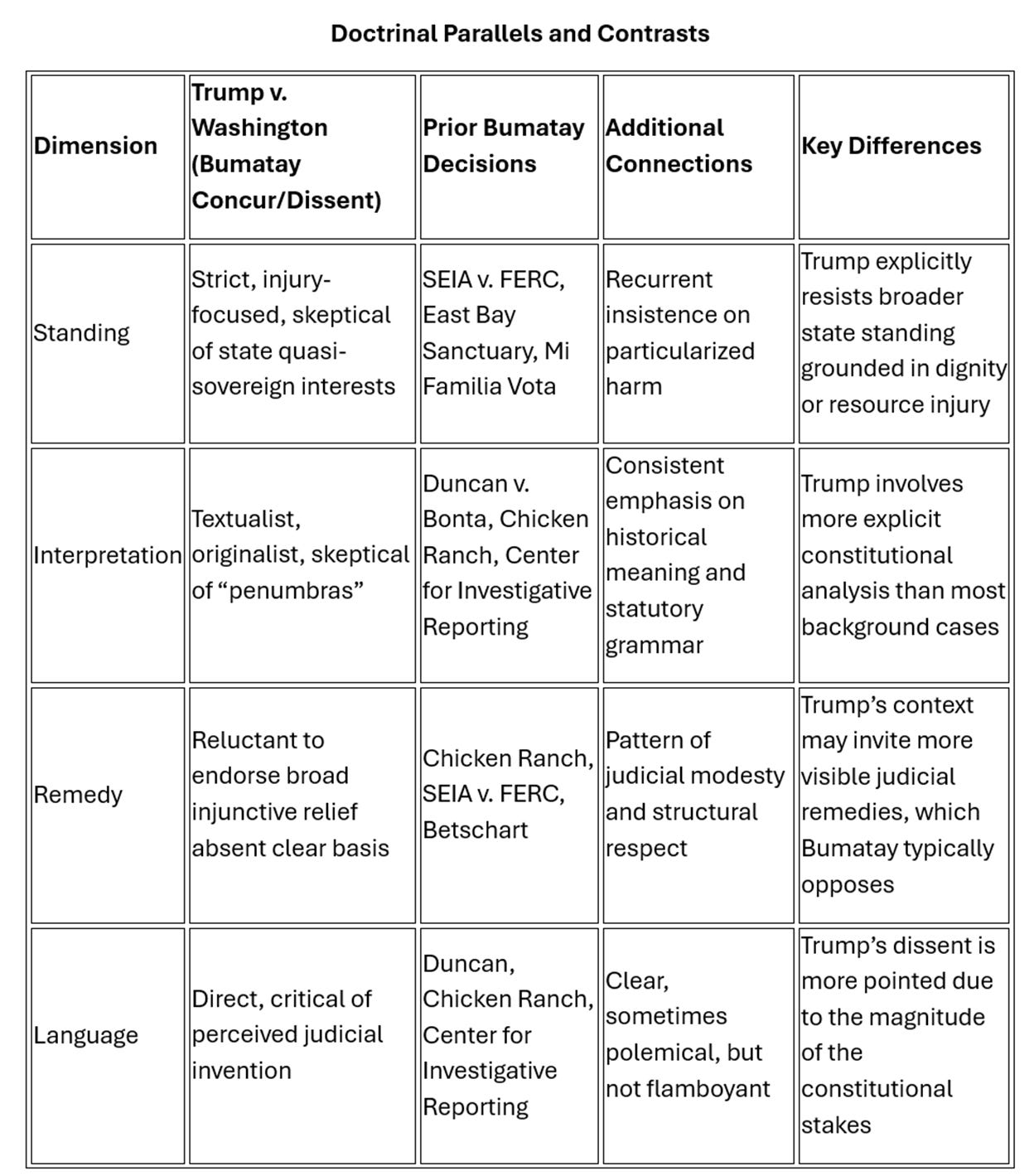

Judge Bumatay’s Jurisprudence in Trump v. Washington in Context

Doctrinal Foundations and Standing

In Trump v. Washington, Judge Bumatay’s partial concurrence/dissent reflects an approach found throughout his background opinions: textual rigor, institutional separation of powers, and skepticism of novel expansions of standing. Bumatay’s view in Trump—questioning whether the states’ alleged injuries met the standard for Article III standing—tracks his pattern in cases like East Bay Sanctuary Covenant and Mi Familia Vota, where he repeatedly insists on a “concrete, particularized, and judicially manageable” injury. His dissent in Solar Energy Industries Association v. FERC likewise demonstrates resistance to procedural or environmental standing based on speculative or attenuated theories of harm.

Where other panels have sometimes embraced broader “quasi-sovereign” state interests or relaxed procedural standing (as in Safe Air or Kootenai under the Gould model), Bumatay’s writing is more constrained: he anchors standing in transparently textual and historical limits, often referencing the Supreme Court’s most restrictive precedents. In Trump, he casts doubt on whether the risk to state resources, or to “state dignity,” suffices for federal court intervention—a stance foreshadowed in his environmental and FOIA dissents.

Constitutional and Statutory Interpretation

Bumatay’s Trump opinion exhibits his core method: exacting textualism, originalist reasoning, and aversion to implied rights or penumbras. Like his dissent in Chicken Ranch Rancheria (IGRA case), he starts with the constitutional or statutory language, mapping it against contemporaneous historical sources and Supreme Court touchstones. In Trump, his reading of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause is “anchored in text, structure, and original meaning,” rejecting what he characterizes as judicial policy-making.

This is a consistent pattern: in Duncan v. Bonta (Second Amendment/magazine ban), he hews closely to constitutional text, original intent, and Supreme Court precedent, sharply delimiting judicial innovation. In Center for Investigative Reporting v. DOJ, he objects to statutory “entrenchment” doctrines not found in the statutory language. Across his opinions, Bumatay’s method resists broad constructions not compelled by the text—eschewing, for example, “purpose-driven” or “functional” arguments when they might disrupt the constitutional order.

Remedies and Judicial Role

In his Trump partial concurrence/dissent, Bumatay’s approach to remedy and judicial restraint mirrors his Chicken Ranch dissent: courts should not order structural relief unless the statutory or constitutional predicates are unmistakably met. He frequently warns against judicial overreach, urging that remedial powers should not “vitiate the separation of powers” or create “novel forms of relief” absent clear textual authorization.

This echoes his skepticism in Solar Energy Industries Association (remand without vacatur, judicial review under NEPA) and his refusal to innovate procedural rights in Betschart v. Oregon (pretrial habeas/class action). Bumatay’s remedies are bounded, tailored, and structurally respectful.

Language and Doctrinal Views

Bumatay’s prose is direct, declarative, and polemically clear—but usually avoids rhetorical excess. In Trump, he emphasizes “the original meaning of the Citizenship Clause” and warns against “judicially invented exceptions.” This is consistent with his tone in Duncan and Chicken Ranch, where he stakes out the consequences of what he sees as doctrinal deviation (“judicial entrenchment,” “sidestepping plain text”) while insisting that only Congress or the Supreme Court should alter well-settled rules.

Unlike Judge Gould—whose pragmatism occasionally tempers his text-first approach—Bumatay rarely accommodates practical or policy-driven exceptions. The result is a jurisprudence that is sometimes narrower, but predictably so.

Bumatay’s Trump v. Washington concurrence/dissent fits squarely within his established jurisprudence: rigorous textualism, fidelity to original meaning, and institutional modesty. His partial dissent resists both novel expansions of standing and broad constitutional remedies—prioritizing the limits and roles set by constitutional text and precedent. This distinguishes his approach from more pragmatic or policy-sensitive jurists, and brings a predictable, if sometimes austere, perspective to the court’s handling of contested constitutional controversies.

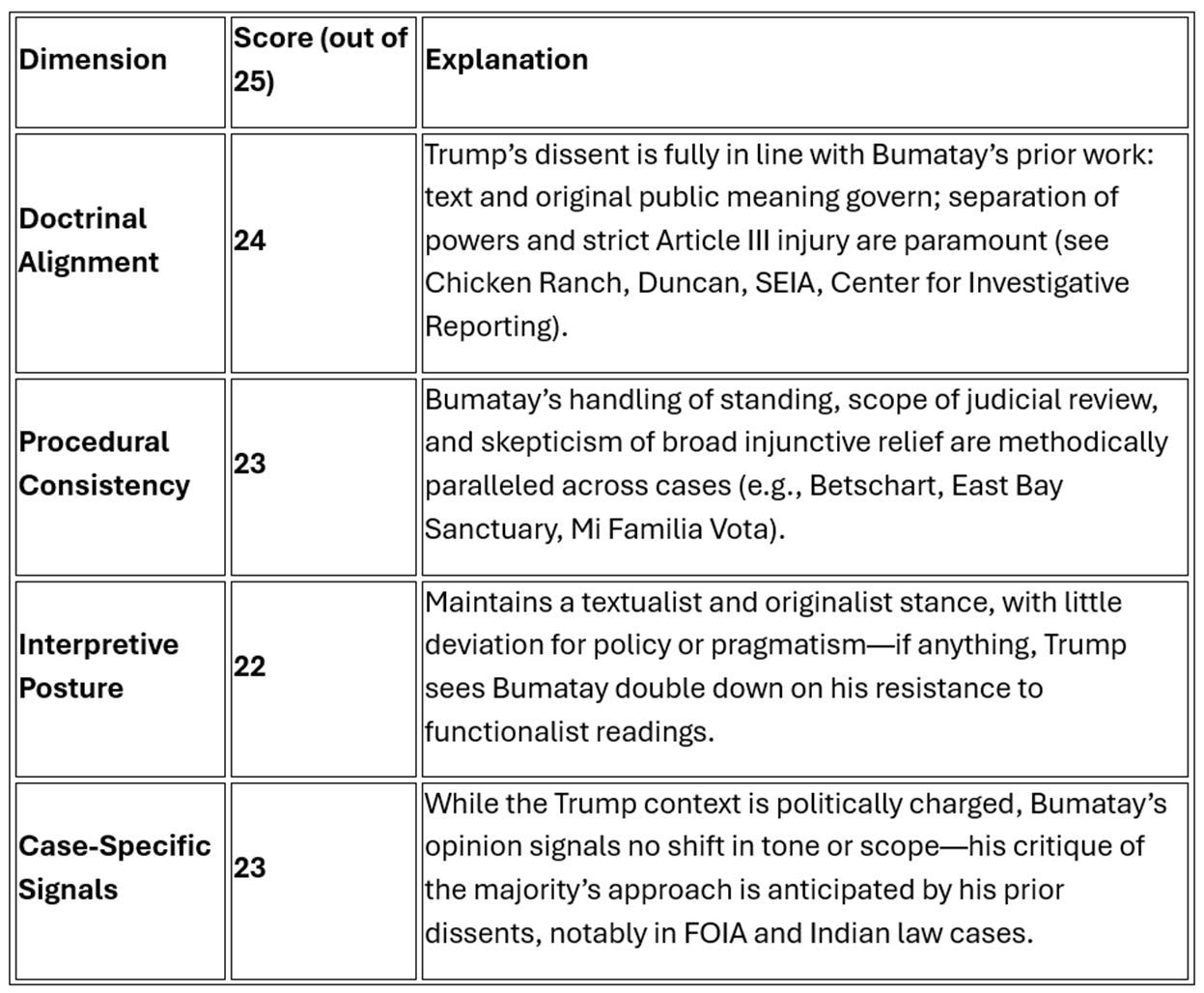

Judge Bumatay (92/100) demonstrates exceptional predictability, with his Trump v. Washington concurrence/dissent closely mirroring his established approach to text, standing, and constitutional separation of powers. Across the sampled decisions, Bumatay’s jurisprudence is marked by a disciplined textualism, a cautious approach to standing, and an institutional humility regarding the judiciary’s remedial reach. The Trump case presents an unusually high-profile and high-stakes forum for these themes, but Bumatay’s opinion is—if anything—even more insistent on doctrinal limits and original meaning than in his prior, sometimes more technical, dissents.

Judge Bumatay’s approach in Trump v. Washington is a model of jurisprudential constancy. Whether in the context of environmental standing, regulatory disputes, or hot-button constitutional litigation, his work provides clear advance notice to litigants: doctrinal boundaries matter, and the court will not stretch them to accommodate the political moment. This predictability is not only a matter of professional style, but a form of judicial integrity—a check against drift or opportunism in high-profile disputes.

Why does this matter for the Trump litigation?

Clarity for litigants: Parties know that Bumatay will hew to textual limits and procedural rigor—arguments from policy or equity are unlikely to prevail absent statutory or constitutional warrant.

Legitimacy and transparency: Especially in contentious national litigation, Bumatay’s disciplined reasoning reinforces public trust that the law, not the news cycle, shapes judicial outcomes.

Benchmark for divergence: Any future deviation by Bumatay from this baseline would be immediately visible—and would carry outsized weight in assessing the trajectory of his judicial philosophy.

Broader implications:

Bumatay’s record offers a “control group” for studying conservative textualist judges in periods of political crisis or constitutional ferment. As the Trump-era legal battles persist (or evolve), those seeking to forecast judicial behavior—whether government counsel, advocacy groups, or fellow judges—can look to Bumatay’s consistency as a predictor of outcome, tone, and doctrinal method.

In moments of maximal political stress, predictability in judicial reasoning is itself a constitutional value. Bumatay’s Trump v. Washington opinion exemplifies this—not because it resists controversy, but because it resists the gravitational pull of the moment in favor of continuity and law.

Why Bumatay Scores Higher:

Doctrinal Rigidity Across Domains:

Bumatay’s Trump opinion mirrors the tone, scope, and method of his prior dissents almost exactly—whether in cases about energy regulation (CRA v. Berkeley), tribal-state compacts (Chicken Ranch), or standing doctrine (Mi Familia Vota). There is no perceptible adaptation to the political or constitutional scale of the Trump case.Remedial Minimalism and Article III Formalism:

While Gould’s remedy was doctrinally justified, it expanded his usual scope in light of the issue’s gravity. Bumatay, by contrast, applies the same narrow remedial logic and Article III standing rigor seen in Betschart and SEIA, refusing to broaden judicial reach despite national implications.Tone and Language Consistency:

Gould’s Trump opinion—though measured—takes on a more assertive constitutional tone than seen in earlier administrative law decisions. Bumatay’s dissent, however, reads exactly like his prior work: restrained, originalist, and laser-focused on statutory limits.

Where Gould Diverges Slightly:

Gould remains doctrinally consistent but allows modest evolution in interpretive posture and remedy to match the constitutional scale of the case. His Trump opinion reveals a judicial willingness to more assertively defend federalism and citizenship guarantees, which slightly extends beyond his prior rulings on environmental and statutory matters.

Bottom Line

Judge Bumatay scores higher not because his jurisprudence is “better,” but because it is more internally rigid and less reactive to context. His dissent in Trump v. Washington is almost indistinguishable in method and tone from his prior dissents—reflecting a tightly bounded judicial philosophy. Gould, by contrast, shows a more responsive and context-aware application of long-held principles, leading to a small but meaningful shift in interpretive force.

Who Is Right? A Jurisprudential Fork in the Road

On internal consistency, Judge Bumatay is the more rigidly stable voice. Across dissents in domains as varied as administrative law, energy regulation, and constitutional federalism, his interpretive method—text-first, structure-bound, and skeptical of judicial remedy—is virtually unchanged. The Trump v. Washington dissent follows that template precisely. If predictability means methodological uniformity regardless of political context, Bumatay prevails.

Judge Ronald M. Gould, by contrast, is predictably methodical but contextually responsive. He adheres to textualism and procedural rigor, but in Trump v. Washington, his opinion shows an assertiveness that reflects the constitutional weight of the case. While still grounded in precedent, Gould allows his role as judicial guardian to guide how text and history apply in existential moments.

Who Is Right Depends on What You Believe the Judiciary’s Role Is:

Gould is right if you believe that:

The Constitution’s structural guarantees—like birthright citizenship—demand a judiciary capable of assertive protection when executive power overreaches.

Standing doctrine and remedial scope must flex slightly to preserve fundamental rights in moments of systemic stress.

History, precedent, and purpose illuminate constitutional text and deserve weight alongside grammatical reading.

Bumatay is right if you believe that:

The judicial branch’s most vital contribution is restraint and clarity, even in politically charged cases.

Text and structure alone should guide constitutional adjudication, and departure from procedural thresholds (like standing or justiciability) risks unprincipled expansion.

Remedies should never scale up simply because the stakes are high—judicial power must be constant, not reactive.

The question isn’t only who reached the better outcome—it’s what kind of legal system we trust to adjudicate political controversy. Gould models a judiciary that flexes to preserve rights; Bumatay models one that resists the pull of the moment. One guards liberty through engagement, the other through restraint.

If you enjoyed this post and haven’t subscribed, please think about doing so and about sharing the post with others. Paid subscribers get access to an additional set of articles.

The above said, I admire the bias-free language here—the author’s, not Gould’s.

Excellent, as usual. I am particularly admiring of Judge Gould - his steadfast reasoning - although, for reasons known only to him, he is determined to live in Seattle as opposed to lovely, welcoming San Francisco. Some people!