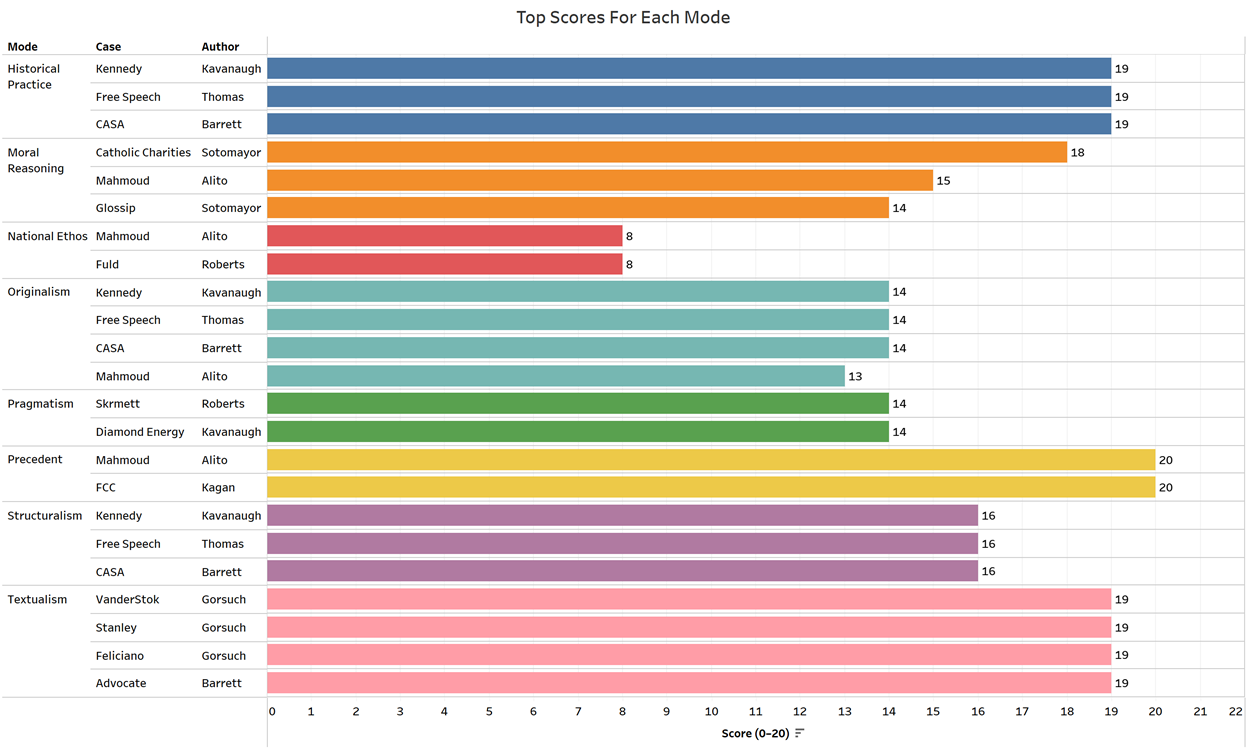

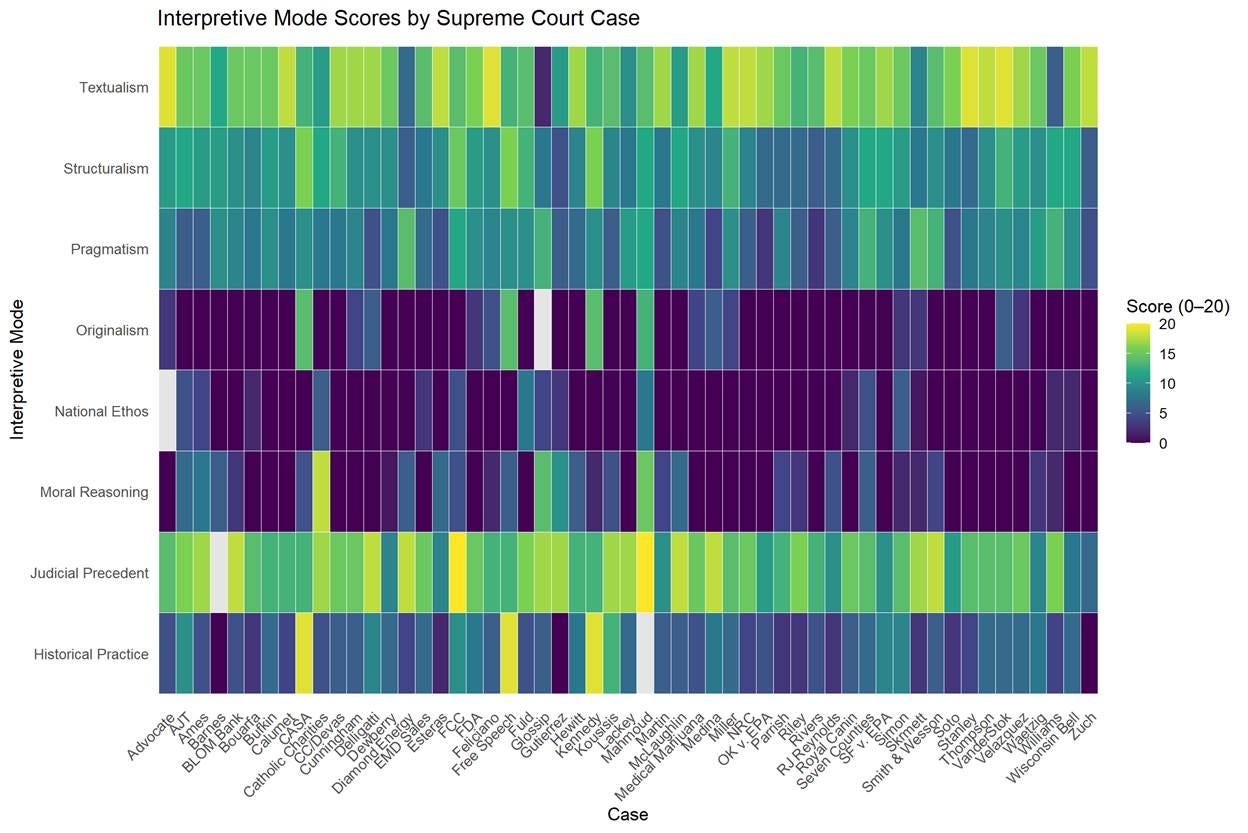

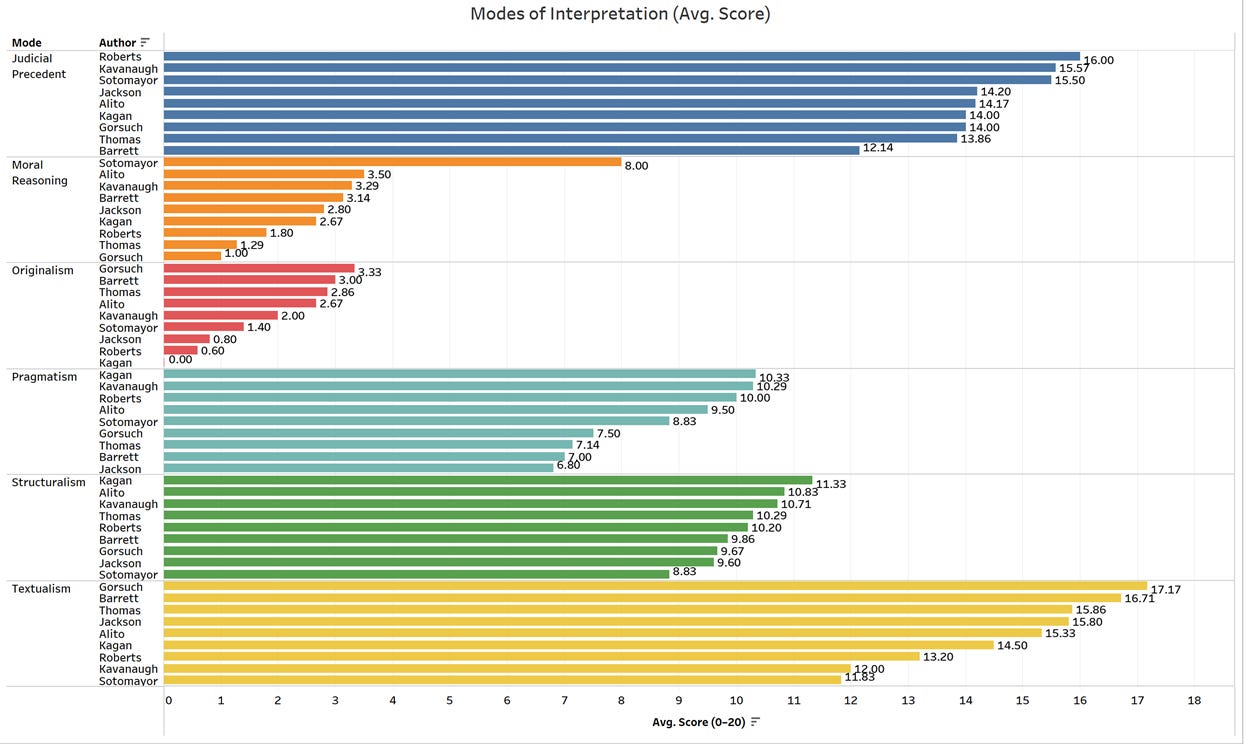

Measuring the Modes

How did the Justices leverage modes of interpretation this past term? This article uses empirical measures to track just how much originalism, pragmatism and more were applied in majority opinions.

CASA as an Example

In one of the most anticipated decisions of this past Supreme Court Term, Trump v. CASA, Justice Barrett’s majority opinion opens not with a conventional doctrinal dispute but with a framing question about the federal judiciary’s authority to issue universal injunctions. From the outset, the opinion signals its interpretive posture through an appeal to legal tradition and statutory constraint: “A universal injunction can be justified only as an exercise of equitable authority, yet Congress has granted federal courts no such power.” This invocation reflects a fusion of textualism and historical practice, where the boundaries of judicial power are delimited by the text of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and the remedies “traditionally accorded by courts of equity.” The Court’s insistence that equitable relief must align with the “broad boundaries of traditional equitable relief” underscores a deep commitment to original meaning—specifically, to what was understood as proper judicial power at the time of the Constitution’s ratification and early congressional enactments. Phrases such as “the universal injunction was conspicuously nonexistent for most of our Nation’s history” and “equity is flexible, but its flexibility is confined” further illuminate a historicist approach grounded in Founding-era institutional understandings.

The opinion does not rest solely on historical or textual constraints. Barrett also introduces structuralist reasoning by emphasizing the separation of powers as a guiding constitutional value. The Court warns that expansive remedial practices risk transforming the judiciary into an “imperial Judiciary,” destabilizing the structural equilibrium among branches. In addition, there are elements of pragmatism in the Court’s acknowledgment of the practical harms posed by universal injunctions—including forum shopping, asymmetric litigation incentives, and the rush to obtain emergency relief. While the Court largely avoids moral reasoning or overt appeals to national ethos, its methodical recitation of the institutional consequences of judicial overreach reflects an implicit concern with the judiciary’s legitimacy and role within the constitutional order. This blending of interpretive tools—textual, historical, structural, and prudential—makes CASA an illuminating case for empirically identifying and coding the modes of constitutional interpretation in judicial reasoning.

Tools of Interpretation

The interpretive strategies visible in Trump v. CASA, Inc. reflect longstanding modes of constitutional reasoning that have been systematized in legal scholarship and institutional analyses. The Congressional Research Service’s (CRS) report, “Modes of Constitutional Interpretation” (R45129), offers a structured typology of these approaches, identifying eight distinct interpretive methods—textualism, original meaning, judicial precedent, structuralism, historical practices, pragmatism, moral reasoning, and national ethos. While these categories often overlap in practice, they provide a conceptual framework for disentangling the rhetorical, doctrinal, and institutional tools judges deploy when interpreting the Constitution or federal statutes. The CASA opinion exemplifies how these tools interact: it pairs textual authority with structural design, grounds judicial restraint in Founding-era legal practice, and tempers formalism with institutional pragmatism.

The CRS framework distinguishes each mode by its sources of legitimacy and interpretive orientation. Textualism focuses on the ordinary meaning of constitutional or statutory language at the time of enactment, while original meaning and original intent probe the historical understanding or purposes of the Framers or ratifiers. Judicial precedent centers interpretation within the trajectory of case law, providing doctrinal stability. Structuralism draws inferences from the architecture of the Constitution—such as separation of powers or federalism—whereas historical practice emphasizes long-standing institutional behaviors as interpretive guides. Pragmatism evaluates the practical consequences of legal rules, often used in balance with other modes. Moral reasoning invokes normative principles like liberty or justice, and national ethos appeals to evolving ideas of American identity or democratic values. These modes, while distinct in theory, often interact dynamically in judicial decisions—just as they do in CASA, where the Court’s reasoning builds from original and structural limits, yet also anticipates institutional dysfunction in a modern context. Understanding these modes not only clarifies what judges say, but how they justify the exercise—and limits—of constitutional authority.

Thinking About These Modes

The interpretive techniques deployed in Trump v. CASA do not emerge in isolation but reflect broader debates about constitutional method that span judicial practice and scholarly theory. As Frank Easterbrook contends, originalism and pragmatism are not mutually exclusive rivals but complementary tools: while originalism constrains judges by anchoring judicial authority in text and historical meaning, pragmatism remains essential to democratic governance, allowing institutions to adapt in areas the Constitution leaves open. Meanwhile, Barnett and Solum argue for a more structured theory of original public meaning—one that integrates history and tradition not as independent authorities, but as evidentiary mechanisms to reconstruct the communicative content of constitutional provisions. This approach, they suggest, limits judicial discretion while recognizing the value of long-standing practices when original meaning is under-determinate. In contrast, Andrew Lanham and Jonathan Gienapp offer a sharp historical critique of originalism itself, arguing that founding-era Americans did not see the Constitution as a fixed legal document but as a blend of textual rules, evolving practices, and political contestation. According to this view, originalist methodologies impose anachronistic assumptions on a fundamentally dynamic constitutional tradition. These competing perspectives underscore the centrality—and contestability—of interpretive modes in modern adjudication. The CRS framework, by categorizing these modes into eight distinct but overlapping types, offers a systematic lens for analyzing the very debates that Easterbrook, Barnett, Solum, and Gienapp bring to the fore—providing a bridge from high theory to empirical judicial behavior as seen in CASA and beyond.

The Current Court

In the context of an ideologically polarized Supreme Court, interpretive modes are more than technical frameworks—they are rhetorical battlegrounds for competing visions of constitutional meaning. The justices’ reliance on particular interpretive methods often signals deeper jurisprudential commitments and ideological alignments, shaping outcomes on contested issues such as administrative power, religious liberty, and individual rights. For example, a textualist framing may discipline judicial discretion by confining meaning to fixed linguistic boundaries, while a moral reasoning approach may open the door to evolving principles of justice. As seen in Trump v. CASA, the selection of interpretive mode is not a neutral exercise but a high-stakes choice that influences not only how a case is resolved, but also how judicial authority is legitimized. These modes serve as a form of constitutional currency—distinct yet exchangeable—through which justices mediate between legal tradition and contemporary conflict.

Given the stakes, it becomes imperative to move from impressionistic analysis to empirically grounded evaluation of interpretive behavior. Measuring these modes allows scholars to quantify patterns across decisions, identify methodological consistencies or shifts, and assess claims about judicial restraint or activism with rigor. This article thus turns to operationalizing interpretive modes as measurable variables. For each mode—beginning with textualism and originalism—I identify definitional criteria, diagnostic indicators in judicial language, and scoring rubrics based on evidence from the opinion text. Textualism, for instance, is captured through close attention to the words of a statute or constitutional provision, often with an emphasis on syntax, dictionaries, and formal canons of construction. Originalism, by contrast, is marked by invocations of Founding-era understanding, references to ratification debates, or historical analogies to 18th-century structures. In tracing these patterns, I aim to empirically reconstruct the interpretive architecture that supports judicial reasoning and clarify the normative and doctrinal stakes embedded in each mode.

Measurement

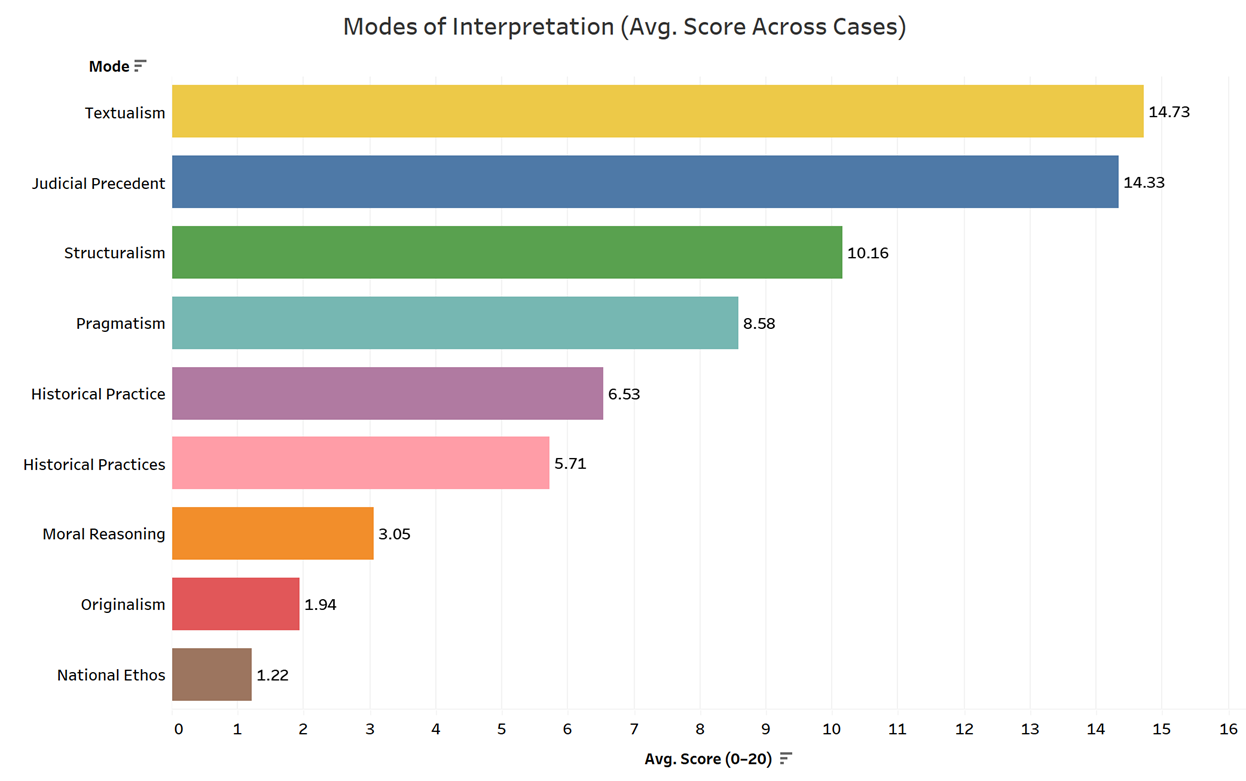

To make interpretive methodology more than a matter of judicial rhetoric, this article constructs a scalable empirical model for identifying and scoring interpretive modes in Supreme Court opinions. Grounded in the eight-category typology outlined by the Congressional Research Service—Originalism, Textualism, Judicial Precedent, Pragmatism, Moral Reasoning, National Ethos, Structuralism, and Historical Practices—the method parses opinion text and quantifies each mode’s presence on a normalized 0–20 scale. Scores are generated through a weighted algorithm that integrates four components: (1) the density of interpretive language per 1,000 words; (2) the frequency and function of legal citations (e.g., precedents, Founding-era materials); (3) the structural integration of interpretive reasoning into the holding versus peripheral dicta; and (4) rhetorical force, such as the use of modal verbs and normative cues.

The technical pipeline proceeds in five stages. First, full opinions are parsed mainly with Quanteda in R to extract sections, tokenize text, and calculate base metrics. Second, interpretive markers are identified using pre-defined dictionaries specific to each mode—e.g., “as originally understood” for Originalism —yielding frequency tables normalized per 1,000 words. Third, all citations are extracted using legal-specific regex patterns, then mapped to interpretive types (e.g., Federalist Papers = Originalism). Fourth, modal verbs (“must,” “may,” “should”) are syntactically mapped to the propositions they govern to assess directive force and framing. Finally, the algorithm weights these metrics into mode-specific scores, using the formula:

Score = 0.35D + 0.25C + 0.20S + 0.20R

where D = density, C = citations, S = structural integration, and R = rhetorical force.

The output is a consistent, reproducible, and analytically rich set of scores that enable comparison within and across cases. The methodology not only detects interpretive technique—it measures its function, weight, and influence in constitutional reasoning.

Deriving Indicators from CRS’s Definitions

1. Textualism: Interpreting constitutional or statutory language based on the ordinary meaning of the text at the time of enactment, without importing external values or policy outcomes.

Indicators:

Phrases like “the text says,” “plain meaning,” “we interpret this provision to mean…”

Use of dictionaries or grammatical analysis.

Attention to clause boundaries, structure, syntax.

Refusal to rely on legislative history or policy concerns.

Scoring Evidence:

Direct parsing of constitutional or statutory language.

Emphasis on fixed textual constraints.

Use of canons of construction (e.g., expressio unius, noscitur a sociis).

2. Originalism

Definition: Interpreting a provision in light of its original public meaning at the time of ratification (for constitutional provisions), or original understanding of the Framers/ratifiers.

Indicators:

References to Founding-era sources, such as The Federalist Papers, debates of the Constitutional Convention, or early statutes.

Historical framing like “at the time of the Founding” or “in 1789…”

Discussion of ratification debates or public understanding.

Scoring Evidence:

Quotes from 18th-century documents.

Discussion of Framer intent or contemporaneous public meaning.

Use of originalist methodology even without citing history directly.

3. Judicial Precedent (Stare Decisis)

Definition: Relying on past judicial decisions as controlling or persuasive authority to guide present interpretation.

Indicators:

Phrases like “as we held in…”, “this Court has long recognized…”

Use of majority opinions from previous Supreme Court cases to structure argument.

Engagement with vertical precedent or horizontal stare decisis.

Scoring Evidence:

Citations to case law that directly structures or constrains reasoning.

Distinguishing or extending prior holdings.

Use of binding precedent as doctrinal baseline.

4. Historical Practice

Definition: Drawing interpretive guidance from longstanding governmental practice, especially inter-branch understandings or political customs.

Indicators:

“Since the Founding, Congress has…”

References to executive or legislative branch practice over time.

Appeals to stability and continuity in institutional behavior.

Scoring Evidence:

Use of customs, traditions, or executive practice to infer meaning.

Reliance on how a clause has been interpreted or implemented over centuries.

Distinction from originalism: practice after ratification matters here.

5. Structuralism

Definition: Inferring meaning from the overall structure of the Constitution, its design, and interlocking institutional roles.

Indicators:

Concepts like “separation of powers,” “federalism,” “checks and balances.”

Descriptions of institutional roles, relationships, or accountability frameworks.

Discussion of implicit powers or duties inferred from constitutional structure.

Scoring Evidence:

Emphasis on preserving hierarchical authority, e.g., executive supervision.

Institutional reasoning grounded in systemic function.

Inference from silence or coordination logic.

6. Pragmatism

Definition: Focus on practical consequences, administrative feasibility, or real-world policy impact.

Indicators:

“Would lead to absurd results…”, “would create unworkable systems…”

Cost-benefit considerations.

References to how regulation functions “on the ground.”

Scoring Evidence:

Concern for administrative burden, implementation, efficiency.

Avoidance of interpretive outcomes that would create chaos.

Empirical data on effects, including economic or policy harms.

7. Moral Reasoning

Definition: Invoking ethical principles, dignity, fairness, or natural rights to interpret a legal provision or justify a holding.

Indicators:

“This result would be unjust…”, “It offends the dignity of…”

References to conscience, equity, or moral values.

Appeals to fairness beyond doctrinal constraints.

Scoring Evidence:

Substantive rights arguments grounded in morality.

Framing outcomes in ethical rather than legalistic terms.

Resonance with civic virtue, human dignity, or conscience.

8. National Ethos (Ethical Identity)

Definition: Invoking core values associated with American identity, such as liberty, democracy, pluralism, or the role of the judiciary in protecting minority rights.

Indicators:

“Our constitutional tradition…”, “American democracy demands…”

Appeals to American values or civic norms.

National self-image as a pluralist or freedom-loving society.

Scoring Evidence:

Express reference to American ideals.

Framing judicial role as protector of national values.

Emotional or symbolic invocation of national purpose.

Scoring Guidelines

16–20: Mode provides central rationale for the decision.

11–15: Strong supporting mode; used with interpretive discipline and depth.

6–10: Clearly present and engaged, but not central.

1–5: Minimal invocation; trace elements.

0: Not present.

Additional Assessment Score:

The importance of legal interpretation to a given case is empirically assessed through a structured review of the judicial opinion’s language and argumentative structure. I assessed how much of the opinion is dedicated to resolving questions of legal meaning, ambiguity, or construction, as indicated by both explicit interpretive analysis (e.g., parsing statutory or constitutional text, examining original meaning, weighing competing interpretations) and the absence of simple, uncontested application of law.

The assessment process uses text-based metrics such as the frequency and length of interpretive passages, the presence of interpretive markers (e.g., “the meaning of,” “as originally understood,” “according to precedent”), and the degree to which the court justifies its decision through interpretive rather than factual or procedural reasoning. These quantitative and qualitative cues are synthesized into a normalized score reflecting interpretive centrality.

When interpretation is crucial—manifest in sustained textual analysis, extended discussion of meaning, or the need to choose between competing readings—the case receives a higher score for interpretive importance. Conversely, where the outcome depends primarily on factual determinations or the straightforward application of clear rules, the score is correspondingly lower. The final score thus represents a proportional, replicable measure of how essential interpretive reasoning is to the disposition of each case. These scores are currently just used as a measurement unrelated to the mode scores that helps to capture the universe of for potentially leveraging the modes in a decision.

Case Level Analyses

The next section provides analyses for certain selected cases.

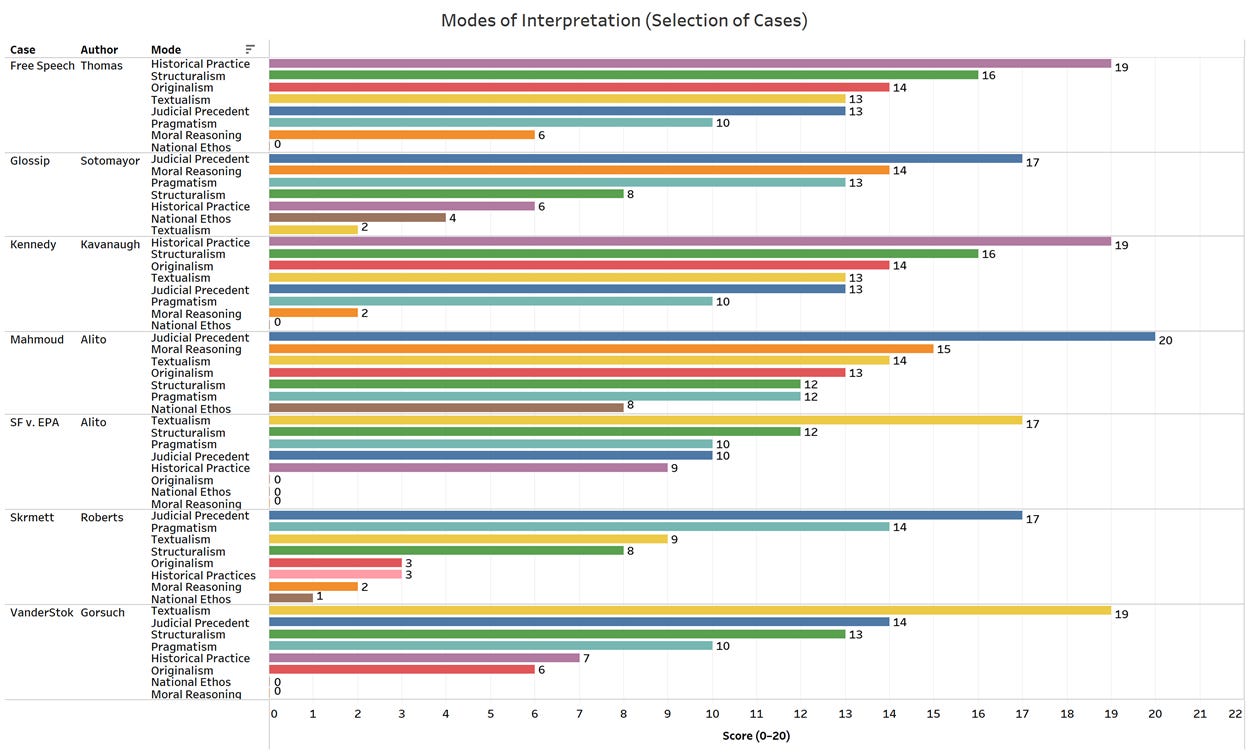

Skrmetti Interpretive Profile: Precedent and Pragmatism Dominate in Transgender Healthcare Ruling

In its most recent term, the Supreme Court upheld Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming medical interventions for minors, with Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion laying out an interpretive blueprint dominated by precedent, pragmatism, and judicial restraint.

Precedent receives the highest empirical weight in the Court’s reasoning—17 out of 20 points (85%)—with the opinion anchored at every turn in established doctrine. Roberts cites Romer v. Evans, Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc., and United States v. Virginia, emphasizing that “[t]he Fourteenth Amendment’s command that no State shall ‘deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,’ U. S. Const., Amdt. 14, §1, ‘must coexist with the practical necessity that most legislation classifies for one purpose or another, with resulting disadvantage to various groups or persons’” (slip op. at 8, quoting Romer, 517 U. S. 620, 631). The Court reiterates that if a law “neither burdens a fundamental right nor targets a suspect class, we will uphold the legislative classification so long as it bears a rational relation to some legitimate end” (id.). Roberts concludes, “We generally afford such laws ‘wide latitude’ under this rational basis review, acknowledging that ‘the Constitution presumes that even improvident decisions will eventually be rectified by the democratic processes’” (Cleburne, 473 U. S. 432, 440).

Pragmatism, scoring 14/20 (70%), shapes much of the Court’s deference to the state legislature’s medical judgment. Roberts details how “recent years” have seen “health authorities in a number of European countries … raise significant concerns regarding the potential harms associated with using puberty blockers and hormones to treat transgender minors.” He catalogs warnings from Finland, England, Sweden, and Norway that the medical evidence is “highly uncertain,” “of very low certainty,” and that the “risks … currently outweigh the possible benefits” (slip op., at 3–4). Citing the 2024 Cass Review in the UK, the opinion notes that “the evidence concerning the use of puberty blockers and hormones to treat transgender minors is ‘remarkably weak,’” and that there is “no good evidence on the long-term outcomes of interventions to manage gender-related distress” (id., at 23–24). The Court observes, “Recent developments only underscore the need for legislative flexibility in this area.”

Textualism registers at 9/20 (45%), visible in the opinion’s parsing of the statute’s terms. Roberts writes, “SB1 incorporates two classifications. First, SB1 classifies on the basis of age. … Second, SB1 classifies on the basis of medical use. … Classifications that turn on age or medical use are subject to only rational basis review” (id., at 9–10). Rejecting the claim that the statute draws sex-based lines, the Court says, “SB1 prohibits healthcare providers from administering puberty blockers and hormones to minors for certain medical uses, regardless of a minor’s sex. … [T]he mere use of sex-based language does not sweep a statute within the reach of heightened scrutiny” (id., at 11).

Structuralism receives 8/20 (40%), as the majority underscores institutional modesty and legislative primacy: “We afford States ‘wide discretion to pass legislation in areas where there is medical and scientific uncertainty’” (Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U. S. 124, 163).

Historical practice and originalism are nearly absent, at 3/20 (15%) each. The opinion traces the evolution of WPATH guidelines since 1979, but only as background: “The standards addressed two treatments in particular: hormonal sex reassignment … and surgical sex reassignment. … They recognized the extensive and sometimes irreversible consequences of hormonal therapy and sex reassignment surgery and acknowledged that some individuals who undergo reassignment procedures later regret their decision” (id., at 2).

Moral reasoning is almost wholly omitted—2/20 (10%)—with Roberts explaining, “Our role is not ‘to judge the wisdom, fairness, or logic’ of the law before us … but only to ensure that it does not violate the equal protection guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment” (id., at 24, quoting FCC v. Beach Communications, 508 U. S. 307, 313).

National ethos, with the lowest mark at 1/20 (5%), is visible only in passing reference to the prerogative of “the people, their elected representatives, and the democratic process” to resolve policy debates (id., at 24).

The empirical table shows that precedent and pragmatism account for over 60% of the opinion’s analytical weight. The interpretive depth score lands at 12/20 (60%), consistent with an approach that is doctrinally disciplined, methodologically coherent, and procedurally restrained. As Roberts concludes, “The Equal Protection Clause does not resolve these disagreements. Nor does it afford us license to decide them as we see best. … Having concluded it does not [violate equal protection], we leave questions regarding its policy to the people, their elected representatives, and the democratic process” (id., at 24).

Output Table

The table below breaks down the certain individual components that make up the mode scores in Skrmetti.

Glossip v. Oklahoma: Precedent-Driven Constitutional Adjudication with Moral and Institutional Urgency

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s majority opinion in Glossip v. Oklahoma marks a robust reaffirmation of prosecutorial due process doctrine, rooted almost entirely in Supreme Court precedent and shaped by the Court’s conception of its institutional gatekeeping role in capital cases. The opinion, which spans 11,236 analyzed words, was handed down by the Supreme Court on February 25, 2025, and is defined by a nuanced layering of doctrinal rigor, pragmatic remedy, and pronounced moral concern.

The interpretive mode distribution is dominated by judicial precedent, which accounts for 17 out of 20 points, or roughly 36% of all modal content. Phrases such as “Napue held…,” “as we explained in…,” and “this Court has maintained…” appear throughout the text, making clear that the Court views the materiality standard set forth in Napue v. Illinois as the “central organizing authority.” Citations to Brady v. Maryland, Giglio v. United States, Kyles v. Whitley, and Chapman v. California reinforce a strict precedent-driven approach. Doctrinal analysis is anchored in prior case law, with no deviation from the established materiality test for prosecutorial error.

Pragmatism emerges as the second most significant interpretive force, scoring 13/20 and representing about 18% of the opinion’s modal content. Justice Sotomayor repeatedly highlights the practical risks of wrongful execution, procedural manipulation, and “judicial economy” in a system where “execution [is] imminent” and the process has been marked by a “decades-long failure.” The Court’s refusal to remand or further delay is explicitly justified by the need to prevent ongoing harm and to preserve the legitimacy of the judicial system.

Moral reasoning is woven deeply into the opinion’s tone and logic, scoring 14 out of 20 (22% of modal content). Phrases such as “grave doubt,” “disturbing revelations,” and “horrifies me” underscore a sense of ethical urgency that transcends mere legal technicality. The opinion does not shy away from direct acknowledgment of the human and social stakes involved in capital punishment, explicitly invoking the state’s “betrayal of public trust” and the need to maintain “confidence in the verdict.” Justice Sotomayor’s language frequently signals an underlying commitment to fairness and legitimacy, framing the remedy as not only doctrinally required but also morally imperative.

Structuralism is also prominent, scoring 8/20 and appearing in about 10% of modal content. The opinion asserts the judiciary’s “constitutional obligation” and “responsibility and duty to correct” prosecutorial misconduct, positioning the Court as a key guardian of institutional integrity and due process. Citations to Giglio, Napue, and Ake v. Oklahoma are used to highlight the longstanding gatekeeping function of the courts in correcting state overreach.

Historical practices contribute to the reasoning with a score of 6 out of 20 (7% of content). The opinion references “traditional duty of prosecutors” and invokes long-standing prosecutorial norms dating back to “1796.” This historical grounding links the modern materiality doctrine to a deeper tradition of ethical obligation, reinforcing the expectation that convictions tainted by false testimony must be set aside to preserve the legitimacy of the criminal justice system.

In contrast, textualism and originalism are essentially absent from the Court’s analysis. Textualism registers only 2 out of 20 (2%), with no significant statutory parsing or emphasis on constitutional text. The opinion is doctrinal and case-based rather than text-based. Originalism is entirely omitted (0/20), as the opinion makes no attempt to root its reasoning in the intent of the Founders or the original meaning of constitutional provisions.

National ethos is subtle but not absent, earning a 4 out of 20 (5%). The opinion references the “integrity of the system” and the “interests of the victim’s family,” placing these within the broader context of the constitutional system’s legitimacy and the social values underlying capital punishment. This concern for rule-of-law principles and justice system legitimacy is more implied than directly argued, often emerging in contrast to dissenting opinions that emphasize victim rights.

The interpretive depth score for the Glossip opinion is 16 out of 20, reflecting an exceptionally strong and multidimensional engagement with both precedent and the practical, moral, and institutional stakes of the case. Justice Sotomayor’s ruling is “procedurally precise, doctrinally anchored, and morally engaged,” drawing its power from the “convergence of precedent, institutional integrity, and pragmatic realism.” While the absence of originalist and textualist analysis modestly limits the opinion’s theoretical reach, the opinion stands as a leading example of precedent-driven constitutional adjudication that does not shy from the unique ethical weight of capital cases. The depth and clarity of this approach reinforce the Court’s enduring role as both a disciplinarian of the law and a guardian of justice.

Thompson v. United States: A Showcase of Modern Textualism Anchored by Precedent and Statutory Logic

Chief Justice John Roberts’s majority opinion in Thompson v. United States is a tightly focused exercise in classical textualism, distinguished by its emphasis on statutory language, comparative legislative analysis, and disciplined boundary-setting for criminal liability. Issued by the Supreme Court on March 21, 2025, and running 4,453 analyzed words, the opinion methodically parses the reach of 18 U.S.C. §1014, clarifying that a conviction requires a statement that is factually false—not merely misleading or incomplete.

Textualism is the unmistakable centerpiece of the opinion, accounting for 18 out of 20 possible points, and constituting an estimated 35% of the interpretive content. Roberts’s approach is direct: “We start with the text,” he writes, highlighting that “the statute uses only the word ‘false’.” The opinion turns repeatedly to both historical and contemporary dictionaries—such as Black’s Law Dictionary (1951, 2024) and Webster’s Synonyms (1942)—to confirm that “false means not true.” Roberts’s language is unequivocal: “basic logic dictates” that a statement cannot be simultaneously true and false, and the opinion insists that §1014 “does not criminalize misleading but factually accurate statements.” Throughout, textual analysis is central, as the Court draws sharp lines around the term “false,” reinforcing a formalist reading that guards against the expansion of criminal liability by implication or innuendo.

Judicial precedent plays a prominent but supporting role, scoring 14 out of 20 and comprising about 20% of the modal content. Roberts anchors the interpretation in United States v. Wells (1997) and Williams v. United States (1982), using these cases to clarify that §1014 does not punish omissions, ambiguous statements, or implied falsehoods unless actual falsity is proven. The opinion acknowledges the Government’s arguments based on Kay v. United States and other precedents, but distinguishes them as inapplicable or inapposite, making clear that the Court’s focus remains on whether the defendant’s statements were “not true”—not whether they were potentially misleading.

Structuralism emerges through the opinion’s detailed comparative analysis of statutory context, meriting 10 out of 20 points (15% of modal content). Roberts systematically contrasts §1014’s language with other provisions of Title 18 and related criminal statutes—such as §§1038, 1365(b), and 1515(b)—that explicitly criminalize “false or misleading” statements. He explains, “statutory context confirms” that when Congress intends to sweep more broadly, it does so expressly. This structural logic underscores both the specificity and the deliberate constraint of the statute, reinforcing the majority’s textualist approach by situating §1014 within the larger architecture of federal criminal law.

Historical practice is present as an interpretive backdrop, with a score of 7 out of 20 (10%). The opinion traces the origins of §1014 to its 1948 enactment, drawing on statutory drafting practices from the 1930s and 1940s and referencing language from contemporaneous statutes such as the Public Utility Act (1935) and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (1938). By highlighting that “Congress’s drafting conventions at time of enactment” favored clear, narrow statutory language, the opinion makes clear that the omission of “misleading” was a conscious legislative choice.

Pragmatism also registers, albeit in a modest and controlled fashion, scoring 9 out of 20 and constituting roughly 12% of the opinion’s interpretive content. Roberts deploys real-world hypotheticals—including references to a tennis match and ambiguous statements about surgical outcomes—to illustrate the difference between truly false assertions and statements that are merely open to interpretation. These practical examples serve to clarify the Court’s holding: criminal liability under §1014 attaches only to factual falsity, not to clever misdirection or partial truths. The opinion further acknowledges the need for “jury fact-finding” but warns against expanding statutory scope in ways that could chill ordinary communication or sweep innocent conduct within the reach of federal prosecution.

Originalism, moral reasoning, and national ethos are entirely absent from the interpretive palette. There is no reference to founding-era understanding, proportional punishment, fairness, or broader constitutional identity. Roberts’s methodology is sharply doctrinal and focused on formal legal categories, not on normative or historical abstraction.

The interpretive depth score for this opinion stands at 16 out of 20, reflecting its excellence in textual rigor, doctrinal clarity, and structural coherence. The absence of originalist or moral argumentation, as well as any invocation of national values or ethos, marks the opinion as distinctly formalist and doctrinally narrow. Yet this precision is precisely the opinion’s strength: by “rigorous textual constraint and structural logic,” the Court delivers a replicable, empirically consistent standard for the criminalization of false statements, sharply delineating the boundaries of federal law and reinforcing a core principle of statutory interpretation—that clarity, not expansiveness, should guide judicial construction of penal statutes.

Delligatti v. United States: Precedent-Driven, Textual Fidelity and Statutory Logic in Criminal Law

Justice Clarence Thomas’s majority opinion in Delligatti v. United States stands as a clear example of doctrinal rigor and interpretive discipline in the statutory criminal context. Delivered on March 21, 2025, and spanning 5,258 analyzed words, the opinion clarifies that the phrase “use of physical force” under 18 U.S.C. §924(c)(3)(A) includes not just affirmative acts, but also knowing or intentional omissions that result in bodily injury or death—thus affirming that second-degree murder-by-omission is a predicate crime of violence.

Judicial precedent is the primary interpretive engine, commanding 18 out of 20 points and constituting about 35% of modal content. Thomas’s analysis leans heavily on Supreme Court decisions including United States v. Castleman (2014), Stokeling v. U.S. (2019), Johnson v. U.S. (2010), Voisine v. U.S. (2016), Borden v. U.S. (2021), and Bailey v. U.S. (1995). These cases frame both the meaning and scope of “physical force” and “use.” Castleman’s logic—holding that intentional causation of harm by indirect means can constitute use of force—is repeatedly invoked, as Thomas emphasizes, “as in Castleman,” and “Stokeling makes clear,” relying on a continuous thread of doctrinal development.

Textualism plays a nearly equal role, earning 17 out of 20 points and forming roughly 30% of the modal analysis. The opinion opens with “We start with the text,” and repeatedly parses key statutory phrases: “use of physical force,” “against the person of another,” and “crime of violence.” Thomas draws on statutory language from multiple provisions—such as §924(c)(3)(A), §922(g)(9), and the Model Penal Code—to conclude that neither the text nor ordinary usage restricts criminal liability to affirmative acts. The Court’s parsing of clause structure and individual terms is supported by references to both case law and leading interpretive treatises, reinforcing the conclusion that intentional omissions suffice for “use.”

Structuralism emerges as a significant supporting theme, meriting 10 out of 20 points (15% of content). Thomas carefully situates the reading of “crime of violence” within the broader architecture of federal criminal law, arguing that “elements clause is the natural home” for such crimes and highlighting that the structural placement of the term “ensures that prototypical violent crimes,” including murder by omission, remain within §924(c)’s scope. By contrasting the elements clause with the now-invalidated residual clause (Davis, 2019), and referencing the organizational logic of the criminal code, the opinion underscores the interpretive coherence required across statutes.

Historical practice is used to reinforce both the doctrinal and textual analysis, with a score of 9 out of 20 (12%). The opinion traces the common-law pedigree of omission-based homicide, citing treatises such as Hawkins’ Pleas of the Crown (1716) and influential secondary authorities like LaFave & Scott and Perkins & Boyce. These sources, along with references to historic cases from Montana (1887) and Michigan (1972), establish that omission-based murder was widely accepted as criminally culpable both at common law and in American courts by the time Congress enacted the relevant statute.

Originalism is present, though to a lesser degree (6 out of 20, 5%). Thomas infers legislative expectations and statutory meaning as understood in 1986, when Congress passed the controlling language. References to “prototypical crime of violence” and the legislative background, as well as citations to Scalia’s concurrence in Cruzan v. Director (1990), support the claim that Congress intended to include knowing omissions within the statute’s reach, consistent with prevailing legal and doctrinal norms of the period.

Pragmatism appears modestly, with 5 out of 20 points (7%). The opinion uses hypotheticals—such as poisoning, bleach, or cold abandonment—to illustrate the logical consequences of the Court’s interpretation and to highlight the “passing strange” results that would follow from excluding murder-by-omission from the statute. Thomas’s argument is functional, aimed at preserving prosecutorial predictability and deterrence without unduly broadening the law.

By contrast, moral reasoning and national ethos are absent (0 points each), consistent with the opinion’s formalist and methodologically focused tone. There is no explicit appeal to justice, punishment proportionality, ethical logic, or broader public values. The opinion remains tightly focused on doctrinal, statutory, and historical analysis, avoiding normative rhetoric.

The interpretive depth score for Delligatti is 17 out of 20, reflecting a robust, layered engagement with precedent, statutory text, structure, history, and original legislative purpose. Justice Thomas’s opinion is described as a “robust judicial synthesis of doctrine, statutory logic, and historical fidelity,” grounded in the “clear textual and categorical analysis” that is “appropriately narrow and disciplined.” The opinion’s disciplined avoidance of moral or policy claims exemplifies rigorous, precedent-anchored statutory interpretation in criminal law—demonstrating both fidelity to established doctrine and a clear path for future application.

Bondi v. Vanderstok: Textual Mastery and Structural Logic in Administrative Statutory Review

Justice Neil Gorsuch’s majority opinion in Bondi v. Vanderstok stands out as one of the most textually rigorous and methodologically sophisticated administrative law rulings of the Supreme Court’s 2025 Term. The case, decided on March 26, 2025, addresses whether the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) exceeded its statutory authority under the Gun Control Act (GCA) when it redefined “firearm” to include certain weapon parts kits and unfinished receivers. Across 8,318 words, Gorsuch constructs an interpretive edifice grounded in precise statutory language, legislative context, and functional realism.

Textualism forms the bedrock of the opinion, accounting for 19 out of 20 possible points and an estimated 38% of modal content. Gorsuch repeatedly signals his methodology with phrases like “We start with the text,” and “the statute says,” launching a thorough parsing of statutory terms such as “firearm,” “weapon,” “frame,” and “receiver.” The analysis is undergirded by references to canonical dictionaries from 1968—the GCA’s year of enactment—and supported by linguistic authorities including Webster’s and the Oxford English Dictionary. Gorsuch interprets “frame” and “receiver” as “artifact nouns,” invoking analogies to unfinished objects like IKEA tables and incomplete novels to explain why certain incomplete components can still be regulated as “weapons” under the law. This focus on “ordinary meaning” and contextually anchored definitions shapes the core doctrinal outcome, as Gorsuch holds that the ATF’s rule swept beyond the statute’s permissible reach.

Judicial precedent is present but secondary, earning 14 out of 20 points and making up about 20% of interpretive content. Gorsuch cites cases such as INS v. National Center for Immigrants’ Rights, Abramski, Stokeling, and Cutter v. Wilkinson, but he emphasizes that precedent’s function here is to clarify the scope of review, not to dictate the meaning of the statute. Prior cases are used mainly to buttress the argument that courts should avoid novel expansions of administrative authority unless clearly permitted by statute, and Gorsuch is careful to leave unresolved questions—such as the regulation of AR-15 receivers—when the record below is undeveloped.

Structuralism is woven deeply into the analysis, with a score of 13 out of 20 (16%). The opinion harmonizes the meaning of “frame or receiver” across multiple statutory provisions, particularly §§921 and 923(i), insisting that a consistent reading is required for regulatory coherence. Gorsuch places great weight on the “framework” of the Gun Control Act, using neighboring sections to reinforce the limited, defined scope of ATF authority. By contrasting statutory structure with the agency’s shifting regulatory interpretations (e.g., ATF guidance from 2013–2020), Gorsuch reinforces the need for interpretive integrity across the entire legislative scheme.

Pragmatism also plays a notable role, scoring 10 out of 20 (12%). Gorsuch infuses his textual analysis with real-world context—citing ATF tracing data (with ghost gun recoveries jumping from 1,600 in 2017 to 19,000 in 2021), enforcement realities, and the proliferation of “Buy Build Shoot” kits. He uses practical hypotheticals—such as the ease of assembling a weapon from a kit, YouTube assembly guides, and analogies to furniture and novels—to illustrate why a plain-meaning approach is both functionally realistic and necessary for legal predictability. These pragmatic considerations support a conclusion that regulatory authority must be clear and bounded if the criminal law is to remain enforceable.

Historical practice provides further support, with 7 out of 20 points (8%). Gorsuch refers to decades of ATF enforcement and Federal Register rulemaking to establish a pattern of regulatory consistency since the GCA’s inception in 1968. The opinion situates the statutory meaning of “firearm” and related terms in the context of both post-1968 administrative practice and the legislative background of earlier federal gun laws, including the 1938 Federal Firearms Act.

Originalism has a more modest presence, at 6 out of 20 (5%). The opinion draws on 1968-era dictionaries and congressional context to reinforce what “Congress would have understood” by the relevant terms at the time of the GCA’s passage. This evidence is marshaled to buttress, rather than drive, the textualist outcome.

Moral reasoning and national ethos are absent (0/20 each), in keeping with Gorsuch’s formalist approach to administrative cases. There are no appeals to civic virtue, constitutional values, or justice-based rhetoric; the focus remains tightly on statutory interpretation and regulatory authority.

The interpretive depth score for Bondi v. Vanderstok is 18 out of 20, reflecting Gorsuch’s blend of textual rigor, structural coherence, and operational logic. The opinion’s hallmark is its ability to merge semantic clarity with practical enforceability, producing a clear standard that both courts and agencies can apply. By eschewing normative abstraction and focusing on the realities of statutory language and real-world application, the Court sets a high bar for methodological sophistication in administrative law, ensuring that legislative meaning, not agency ambition, remains the guiding constraint on federal regulatory power.

Medical Marijuana v. Horn: Textual Anchoring and Precedent Discipline in Civil RICO Litigation

Justice Barrett’s majority opinion in Medical Marijuana, Inc. v. Horn is a definitive example of disciplined textualism, tightly coordinated with doctrinal precedent and moderate structural analysis. Issued by the Supreme Court on April 2, 2025, and spanning 9,520 analyzed words, the opinion resolves whether a plaintiff’s injury “in his business or property” under civil RICO requires a distinct “racketeering injury” or whether any compensable harm suffices.

Textualism is unmistakably the controlling interpretive force, responsible for 17 out of 20 possible points and about 35% of the opinion’s modal content. Barrett structures the entire decision around the ordinary meaning of “injured in his business or property,” opening with, “The ordinary meaning of the statutory phrase guides our analysis,” and maintaining that theme throughout. She draws on multiple dictionary sources—Black’s, Webster’s, Ballentine’s, and American Heritage—comparing nuanced definitions of “injured,” “business,” and “property.” Barrett is explicit in privileging “injury as harm” rather than “injury as legal-right invasion,” concluding that RICO’s §1964(c) adopts a broad understanding of compensable injury. She sharply distinguishes “injured” from “damages” and rejects reading the phrase as a technical term of art, keeping the focus on ordinary usage rather than esoteric legislative intent.

Judicial precedent reinforces this textual conclusion, scoring 15 out of 20 and accounting for 28% of the interpretive content. Barrett deploys a comprehensive line of RICO cases—Sedima, Holmes, Bridge, Yegiazaryan, RJR Nabisco, Apple, Brunswick, Anza, Hemi, and Radiant Burners—not as fallback authority, but as doctrinal pillars that confirm the textual reading. She emphasizes that the Court’s RICO jurisprudence has never required a special “racketeering injury,” tracing this principle back to Sedima and reaffirming it through Holmes and Bridge. Notably, Barrett rebuffs the analogy to antitrust’s “antitrust injury” doctrine, stating that civil RICO stands apart both in statutory language and remedial structure.

Structuralism operates in the background, scoring 10 out of 20 (13%). Barrett references the structure of RICO—including predicate acts, treble damages, and venue provisions—to situate §1964(c) within the larger remedial and jurisdictional framework. She draws an explicit contrast with the Clayton Act’s antitrust structure, resisting the invitation to import analogical constraints that would narrow RICO’s reach. While structural context is never allowed to overshadow the text, it serves as a check against strained or context-insensitive readings.

Pragmatism plays a clear but modest role, with 8 out of 20 points (10%). Barrett recognizes the practical implications of the Second Circuit’s approach, including the risk of transforming all business torts into RICO claims and the resulting pressure on judicial resources. However, she contains these concerns by emphasizing established RICO requirements such as direct injury and a pattern of racketeering, noting that “policy worries about RICO’s scope are for Congress to resolve.” Pragmatic factors are acknowledged, but never permitted to drive the statutory construction.

Historical practice appears only in a supporting capacity, with 5 out of 20 points (6%). Barrett observes that RICO litigation has shifted since 1970, with more suits now filed against “ordinary businesses” than mafia enterprises, but this insight is used descriptively rather than as a prescriptive guide. She references Sedima to note how the law has evolved, yet insists the meaning of “injury” must be drawn from statutory text and the ordinary meaning at enactment.

Original meaning is the least emphasized among invoked methods, with 4 out of 20 points (4%). Barrett briefly discusses contemporaneous dictionary definitions from the 1960s and early 1970s to confirm her reading of “injured,” but she is clear that this is only a semantic clarification—never a search for constitutional or originalist principle.

Moral reasoning and national ethos are entirely absent (0/20 each). The opinion is methodologically precise and avoids appeals to fairness, justice, or broader policy values. Barrett declines to frame the case as a contest of social interests or public identity, focusing strictly on statutory logic.

The interpretive depth score for Medical Marijuana, Inc. v. Horn is 17 out of 20, reflecting a highly rigorous and empirically consistent application of textualist and doctrinal modes, with careful structural and pragmatic moderation. Barrett’s reasoning sets a high standard for empirical, text-driven statutory analysis in civil law, avoiding unwarranted analogies and maintaining fidelity to the ordinary meaning of statutory terms. While the opinion’s structural scope is limited by its narrow focus on a single statutory phrase, it stands as a model of clarity and restraint in modern Supreme Court interpretation.

Catholic Charities Bureau, Inc. v. Wisconsin Labor & Industry Review Commission: Moral Reasoning and Structural Doctrine in Defense of Religious Neutrality

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s majority opinion in Catholic Charities Bureau, Inc. v. Wisconsin Labor & Industry Review Commission is a forceful reaffirmation of strict religious neutrality in constitutional law, setting a high-water mark for the use of moral reasoning and structural analysis in Establishment Clause jurisprudence. Decided on June 5, 2025, and spanning 6,187 analyzed words, the opinion holds that Wisconsin’s exclusion of Catholic Charities Bureau from a statutory religious exemption—because the organization serves all in need rather than only co-religionists—violates the First Amendment’s requirement of denominational neutrality.

Moral reasoning drives the opinion, scoring 18 out of 20 and accounting for approximately 25% of modal content. Sotomayor centers her analysis on the dignity and equal civic status of faith groups, denouncing state action that “subjects them to disfavored treatment” or treats them as “outsiders to the political community.” She grounds her reasoning in the principle that “true religious liberty” demands respect for each group’s theological choices, especially when the state’s policy would penalize faiths that reject coercive proselytization. The decision consistently frames the harm in terms of civic equality, pluralism, and the imperative that government “may not disqualify charitable organizations based on proselytization preferences.”

Judicial precedent is the principal doctrinal scaffold, with 17 out of 20 and 22% of interpretive content. The opinion invokes Larson v. Valente (1982), Watson v. Jones (1872), Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000), and related cases to establish that denominational classifications require the most searching constitutional scrutiny. Citing “this Court has long held,” Sotomayor insists that government neutrality between religions is both a structural and doctrinal imperative—one that does not depend on governmental motive, but on the fact of facial religious classification. The opinion also leans on Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015) at the scrutiny stage, applying its tailoring principles to expose the state’s inconsistent application of religious exemptions.

Structuralism is a consistent theme, earning 12 out of 20 and 15% of modal content. The decision weaves together the Religion Clauses as “inextricably connected” protections, emphasizing that the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses operate jointly to maintain religious liberty and “fundamental … constitutional order.” Sotomayor describes this dual guarantee as the backbone of the “separation of church and state,” and presents the Religion Clauses as complementary bulwarks against state interference with religious identity and expression.

Textualism is present, if subsidiary, scoring 11 out of 20 (15%). The opinion highlights how the application of Wis. Stat. §108.02(15)(h)(2) “facially differentiates” between religious organizations based on their internal theology. Sotomayor does not undertake a broad reinterpretation of the statute’s language; instead, she explains how the state’s discriminatory reading triggers a direct constitutional conflict, placing the statutory text in tension with the First Amendment’s requirements.

Pragmatism is integrated at the tailoring and scrutiny stages, with 8 out of 20 (10%). Sotomayor points out the “vastly underinclusive” nature of Wisconsin’s scheme—exempting some churches while denying exemption to incorporated nonprofits performing the same functions, or inconsistently covering staff such as janitors and clergy. She notes, “no evidence of need,” and that the state’s asserted justifications are poorly matched to the law’s real-world effects. This functional critique of tailoring reinforces the doctrinal arguments about the state’s failure to fit means to ends.

National identity is invoked as an interpretive value, earning 6 out of 20 (8%). The opinion frames American pluralism and religious liberty as core constitutional norms, arguing that the “rejection of doctrinal sorting by the state” is not merely a procedural rule but a defining feature of civic equality in the United States. Phrases like “political outsiders,” “true religious liberty,” and “our constitutional order” root the opinion in a vision of national ethos that prizes equal citizenship for all faiths.

Historical practice is noted briefly (5 out of 20, 5%), as the opinion recounts how federal and state law has long recognized broad exemptions for religious employers, typically without filtering for theological approaches to proselytization. Sotomayor references the federal standard and practice across more than 40 states to illustrate Wisconsin’s deviation from the norm.

Originalism is not invoked (0/20), and the opinion is notably free of founding-era speculation or appeals to the original understanding of the Religion Clauses.

The interpretive depth score for this opinion is a high 18 out of 20, reflecting the ruling’s rich blend of doctrinal rigor, moral and structural clarity, and measured attention to real-world legal effect. Sotomayor’s approach delivers a “clear and replicable constitutional rule, grounded in precedent and national pluralist values.” The opinion’s methodological sophistication lies in its fusion of moral reasoning and precedent, while avoiding unnecessary textual or historical reconstruction, making it a defining statement on religious liberty and equality in the post-Larson landscape.

Rivers v. Guerrero: Textual Clarity and Doctrinal Discipline in Federal Habeas Procedure

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s majority opinion in Rivers v. Guerrero exemplifies the Supreme Court’s trend toward disciplined statutory interpretation in complex federal procedural disputes. Issued on June 12, 2025, the decision clarifies when a habeas corpus application under AEDPA (the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act) qualifies as “second or successive,” reinforcing strong guardrails against piecemeal or serial litigation.

Textualism anchors the opinion, responsible for 14 out of 20 points and constituting roughly 35% of modal content. The Court’s analysis is tightly bound to the statutory language of 28 U.S.C. §2244(b), parsing what constitutes an “application” and the conditions that make one “second or successive.” Justice Jackson emphasizes that, under AEDPA, this status is generally triggered “once judgment has been entered” by the district court, rather than upon the exhaustion of appellate review. The opinion provides close readings of terms such as “claim” and “application,” situating them within AEDPA’s broader definitional framework and distinguishing among various types of post-judgment filings—such as motions under Rules 59(e), 60(b), or 15—by their functional relationship to finality.

Judicial precedent is nearly as prominent, scoring 13 out of 20 and representing 30% of the opinion’s interpretive content. Jackson relies extensively on Banister v. Davis (2020), Gonzalez v. Crosby (2005), and Magwood v. Patterson (2010), using these cases to define the interpretive boundaries of “second or successive” applications. Precedent is employed not only to police the contours of the statutory scheme, but to clarify how different motions interact with AEDPA’s strict limits: Rule 59(e) suspends finality, while Rule 60(b) attacks it post hoc. The opinion distinguishes the functional purpose of each procedural vehicle, reinforcing doctrinal consistency.

Structuralism is used to situate AEDPA’s procedural requirements within a systemic framework, earning 6 out of 20 (15%). Justice Jackson reads AEDPA as operating akin to a res judicata regime, emphasizing that Congress designed the statute to provide “one fair opportunity” for federal review, with subsequent applications requiring strong gatekeeping and justification. This approach is justified not only by the language of §§2244(b)(1)–(4), but also by the broader need for litigation finality and judicial efficiency. The opinion underscores AEDPA’s “single-final-judgment” policy as a foundational procedural rule.

Historical practice appears more narrowly, with 5 out of 20 (10%). The Court acknowledges Rivers’s argument based on pre-AEDPA circuit precedent, but finds this historical background inconsistent and, if anything, a justification for AEDPA’s current clarity and restriction. The opinion references decisions such as Behringer v. Johnson and Giarratano v. Procunier to highlight the lack of doctrinal uniformity prior to AEDPA’s enactment.

Pragmatism is present only at the margins, scoring 3 out of 20 (5%). Justice Jackson notes that Rivers’s interpretation would “promote inefficiency” and risk “prolonging the case indefinitely,” potentially opening the door to endless, serial filings that frustrate the statute’s core goal of finality. However, the tone remains doctrinal rather than policy-driven: practical consequences are used to reject unworkable interpretations, not to drive the interpretive result.

Originalism, moral reasoning, and national ethos are wholly absent from the opinion (0/20 each). There is no appeal to the original public meaning of habeas statutes, and the opinion is notably silent on questions of fairness, justice, or innocence—resting entirely on statutory and doctrinal logic.

The interpretive depth score for Rivers v. Guerrero is 17 out of 20, reflecting a carefully structured, doctrinally consistent approach that reinforces AEDPA’s strict limitations on serial habeas petitions. The absence of broader civic, moral, or historical appeals limits the opinion’s emotional and philosophical breadth, but highlights its clarity and discipline. Justice Jackson’s opinion ultimately delivers a precise, replicable rule for the circuits, cementing the Supreme Court’s formalist trajectory in federal procedural law.

Diamond Alternative Energy v. EPA: Doctrinal Rigor and Pragmatic Realism in Environmental Standing

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s majority opinion in Diamond Alternative Energy v. EPA is a model of doctrinal discipline and pragmatic judicial reasoning. Decided by a 6–3 vote on June 20, 2025, the opinion addresses the right of fuel producers to challenge California’s electric vehicle regulations as approved by the EPA, focusing squarely on Article III standing and its economic consequences for regulated businesses.

Judicial precedent is the dominant interpretive force, earning 18 out of 20 points and comprising about 40% of modal content. Kavanaugh’s opinion systematically invokes Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, TransUnion, Uzuegbunam, Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, and other landmark cases to anchor the analysis of standing. The Court meticulously applies the traditional test—injury in fact, causation, and redressability—relying on Lujan’s “object of regulation” rule and the recent Alliance decision on third-party market effects. Each precedent is used to frame, not just support, the logic of the outcome: “This Court has explained,” Kavanaugh writes, that regulated parties are not “locked out” of court simply because the economic impact flows through a market chain.

Pragmatism is a strong secondary theme, scoring 14 out of 20 and making up 25% of interpretive content. The opinion is attentive to “commonsense” economic realities, rejecting EPA’s invitation to require “expert affidavits from every automaker” or proof of perfect market transmission. Kavanaugh frequently refers to “predictable market consequences,” “businesses should not be locked out,” and “economic reality,” cautioning that speculative arguments from agencies can “waste the parties’ time” and undermine judicial economy. Footnotes reference recent economic data and trends in electric vehicle sales, reinforcing the opinion’s grounding in real-world impacts.

Textualism is present but more definitional than analytic, earning 7 out of 20 (10%). The opinion quotes the relevant language of Article III, section 2—“injury in fact,” “irreducible constitutional minimum”—and defines standing in constitutional terms, but there is little granular parsing of grammar or syntax. Textual cues are marshaled mainly to confirm and reinforce the doctrinal standards.

Structuralism is subtle but clear, with 6 out of 20 points (10%). The decision underscores the need for a tight relationship between injury and remedy, explaining that judicial relief must “align with injury” and that “targets of regulation should not be locked out” from court. Kavanaugh situates these requirements within the broader framework of judicial separation of powers and adversarial litigation, echoing the logic of Valley Forge and Chief Justice Roberts’s writings on Article III limits.

Moral reasoning is muted but present, at 6 out of 20 (10%). The opinion closes with equity-based concerns, warning against “gamesmanship” and defending the right of private businesses to hold regulators accountable. There is an explicit normative thread: “Courts should exercise caution” not to allow agencies to “evade accountability,” and the system should protect “fair market access” for all affected by federal regulation.

Historical practice is invoked mainly for context, with 4 out of 20 points (5%). The opinion traces the oscillating history of Clean Air Act waiver decisions and the EPA’s shifting stances since 2005, but uses these as background rather than as a source of interpretive rule. References to regulatory timelines and Federal Register notices illustrate administrative inconsistency but do not anchor the legal analysis.

Originalism and national ethos are entirely absent (0/20 each). Kavanaugh’s reasoning avoids appeals to Framers’ intent or civic ideals, remaining focused on precedent, practical consequence, and procedural integrity.

The interpretive depth score for Diamond Alternative Energy v. EPA is 17 out of 20, reflecting a methodical and judicially disciplined approach. Kavanaugh’s opinion combines rigorous doctrinal analysis with pragmatic awareness, ensuring that the Court’s reasoning remains tethered to real-world legal and market dynamics. The decision is notable for its lack of textual exegesis and originalist or ethos-based argument, but it stands as a strong example of consistent, precedent-driven environmental law interpretation that balances doctrinal clarity with the practical realities of modern regulatory litigation.

Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton: Historical and Structural Authority for Modern Age Verification

Justice Clarence Thomas’s majority opinion in Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton delivers a historically anchored, structurally reasoned, and doctrinally disciplined defense of state age verification requirements for online sexual content. Issued on June 27, 2025, the decision upholds Texas’s age verification statute, framing the outcome as the logical extension of both original constitutional understanding and centuries of legal tradition regarding obscenity and child protection.

Historical practice and originalism form the backbone of the opinion, accounting for 19 out of 20 and 14 out of 20 points respectively, together constituting about 40% of modal content. Thomas’s opinion offers a sweeping tour of Anglo-American legal tradition, citing English common law, Founding-era treatises, and 19th-century American statutes to establish that state power to regulate “material harmful to minors” is both “deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.” By the 18th century, the Court notes, prohibitions on obscene material—and particularly on its distribution to children—were well-accepted. The opinion traces this tradition through Rex v. Wilkes (1770), Sharpless (1815), and through a spectrum of state statutes and judicial opinions, emphasizing that the same principles animated postbellum law and persist as a justification for modern regulatory schemes.

Structuralism is nearly as central, with 16 out of 20 points (20%). Thomas’s reasoning is heavily functional: “The power to verify age is a necessary component of the power to prohibit,” he writes, analogizing the state’s authority here to other classic regulatory domains (voting, marriage, alcohol, gun licensing). He invokes general constitutional canons, such as those in Federalist No. 44 and Story’s Commentaries, to argue that enforcement mechanisms are inherent in the grant of regulatory power. The opinion repeatedly frames the Texas law as a “necessary component” of the broader constitutional structure that allows states to safeguard minors from sexual exploitation and harmful content.

Textualism and judicial precedent both play supporting but significant roles, each scoring 13 out of 20 (15%). Thomas carefully parses the Texas statute’s definitions—“sexual material harmful to minors,” “one-third of material”—and applies established tailoring tests to its scope. The opinion rebuts claims of vagueness and overbreadth by closely tracking the definitions back to the standards in Miller and Ginsberg. On precedent, the Court distinguishes Reno v. ACLU, Ashcroft II, and Playboy as products of an earlier technological context, and elevates Ginsberg v. New York and O’Brien as more applicable guides to age-based restrictions. Thomas is explicit in re-situating the doctrinal baseline, explaining that the Court’s more recent “strict scrutiny” precedents for the internet do not displace the state’s core police powers rooted in tradition and text.

The opinion is clear that this is not a content ban on adults but an “incidental burden” required to serve a compelling government interest. Applying the Turner II and O’Brien framework, Thomas argues that Texas’s law is “plainly tailored,” does not suppress protected speech, and aligns with decades of constitutional doctrine permitting reasonable restrictions on access for minors.

Pragmatism is visible throughout (10 out of 20). The opinion addresses the practical reality of online age verification: “It is almost impossible to distinguish a 16-year-old from a 17-year-old” online, and technological solutions are “readily available and already common in comparable fields.” Thomas highlights the inadequacy of parental filters and the “broad adoption” of age checks in analogous contexts (alcohol, gambling), reinforcing that the requirement is both feasible and widely accepted.

Moral reasoning is present but muted (6 out of 20). The opinion references the “longstanding public virtue” of protecting children, the susceptibility of minors to sexual violence and exploitation, and the societal interest in limiting access to harmful material. However, these points serve mainly as background values reinforcing the institutional legitimacy of the law rather than as primary argumentative drivers.

National ethos is not directly invoked (0/20). While the opinion implies a civic concern for social harmony and child welfare, it avoids explicit appeals to American identity or constitutional values beyond the legal and historical record.

The interpretive depth score for this decision is 18 out of 20, reflecting a methodologically rigorous synthesis of historical, structural, and doctrinal reasoning. Thomas’s opinion recalibrates the scrutiny for such laws, asserting a conservative judicial approach that is nonetheless forward-looking in its adaptation to technological change. The Court affirms the legitimacy of traditional state police powers in the digital era—anchored not in modern policy innovation, but in the durable constitutional and historical foundations of the American legal tradition.

Mahmoud v. Taylor: Parental Religious Liberty and the Limits of State Power in Public Education

Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion in Mahmoud v. Taylor represents a doctrinally robust and interpretively layered reaffirmation of Free Exercise protections for religious parents in the context of compulsory public education. Decided on June 27, 2025, the opinion synthesizes more than a half-century of Supreme Court precedent, structural constitutional logic, and moral reasoning to strike down a public school district’s refusal to allow religious opt-outs from curriculum content that conflicts with faith-based upbringing.

Judicial precedent is the clear interpretive cornerstone, receiving 20 out of 20 points and accounting for about 30% of modal content. Alito’s opinion recasts Wisconsin v. Yoder not as a “narrow carveout,” but as a general doctrinal rule that when compulsory education policies impose a substantial burden on parental religious upbringing, strict scrutiny applies. Alito elevates Barnette for its coercion analysis and explicitly distinguishes or rejects counter-precedents cited by the dissent, such as Lyng, Bowen, and Smith. In doing so, he further reaffirms the Court’s commitment to Tinker and Espinoza as part of the broader architecture of religious liberty in education. The use of precedent is both positive—building doctrinal rules—and negative—fencing off unwanted applications and analogies.

Textualism provides the legal anchor, with 14 out of 20 points (15%). The opinion relies on the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause as both the textual and operational limit on state authority, repeatedly quoting and applying the phrase “prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]” to frame both the standard and scope of review. The Constitution’s language is not just cited but made controlling in its practical application to educational policy.

Moral reasoning is foregrounded and empathetic, at 15 out of 20 (15%). Alito describes the parental duty to raise children in faith as a “sacred obligation,” highlighting the psychological, emotional, and spiritual stakes for Muslim, Catholic, Orthodox, and Jewish families in Montgomery County. The opinion discusses the “hurtful” and “insulting” impact of state policies that belittle or stereotype religious views, and links these harms to broader concerns for dignity, respect, and cultural diversity. Family integrity and the real risk of marginalization or psychological distress are treated not as abstractions but as core legal concerns.

Originalism is tradition-centered, scoring 13 out of 20 (10%). While Alito does not cite 18th-century sources directly, the opinion channels founding-era understandings of parental authority and the family as a pre-political unit of moral education. References to Pierce v. Society of Sisters and the historical role of religion in American education underscore that the Free Exercise Clause secures a deeply rooted tradition of family autonomy in the transmission of faith.

Structuralism is significant, earning 12 out of 20 (10%). Alito frames the case as a structural violation, arguing that public education—funded by mandatory taxes and governed by compulsory attendance laws—cannot be leveraged to coerce or penalize religious families. The “unconstitutional conditions” doctrine and the principle of state asymmetry are invoked to show that exclusion from the benefits of public education due to religious objection is constitutionally impermissible.

Pragmatism is used to connect doctrinal harms to practical realities, at 12 out of 20 (10%). Alito marshals data on school budgets, private tuition, and special education services to show the real-world burdens on families forced to choose between their faith and access to essential public services. Parent affidavits detail financial and psychological harms, while inconsistencies in opt-out policies are highlighted to demonstrate both the feasibility and fairness of religious accommodations.

The majority applies strict scrutiny, citing Fulton, Yoder, and Kennedy, and finds that the school district cannot demonstrate a narrowly tailored compelling interest, especially given the exceptions already allowed elsewhere in the curriculum.

National ethos is invoked as a secondary but important theme, at 8 out of 20 (5%). Alito appeals to American pluralism and the Bill of Rights as a protector of minority rights, tying judicial review to the defense of dissenting voices and the American tradition of religious liberty.

The interpretive depth score for Mahmoud v. Taylor is 19 out of 20, underscoring its doctrinal richness and integration of legal, moral, structural, and pragmatic reasoning. Alito’s opinion is not merely a restatement of precedent, but an expansive and context-sensitive defense of religious autonomy in public life, grounded in American tradition and attentive to the lived realities of families affected by public policy. The decision stands as a modern high-water mark for the integration of empirical, doctrinal, and human considerations in the protection of Free Exercise rights.

FCC v. Consumers’ Research: Doctrinal Fidelity and Structural Balance in Nondelegation Doctrine

Justice Elena Kagan’s majority opinion in FCC v. Consumers’ Research delivers one of the Supreme Court’s most precedent-dense and structurally attuned defenses of agency discretion under the Constitution. Decided on June 27, 2025, the case confirms that Congress’s statutory framework for the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) universal service fund satisfies the intelligible principle test and does not violate the nondelegation doctrine.

Judicial precedent is the controlling interpretive force, earning 20 out of 20 points and representing roughly 40% of modal content. Kagan meticulously reconstructs the entire nondelegation line of cases, starting with J.W. Hampton (1928) and continuing through Whitman v. American Trucking (2001), Skinner, American Power & Light, Sunshine Anthracite, Free Enterprise Fund, and more. The opinion draws upon nearly a century of Supreme Court decisions to establish that Congress can delegate regulatory authority so long as it provides an intelligible principle—a standard the Court finds met by §254 of the Communications Act. Precedent is not just cited, but forms the logical and legal backbone of the ruling, as Kagan repeatedly shows how the FCC’s actions are cabined by and consistent with established doctrine.

Structuralism is next in importance, with 15 out of 20 points (15%). The opinion offers a sophisticated account of separation of powers, highlighting Congress’s authority to “seek assistance from its coordinate branches” and underscoring that legislative power remains bounded by “the separation of powers integral to our Constitution.” Kagan repeatedly stresses that the executive can implement but not make law, and rebuts the “combination” theory advanced by the Fifth Circuit. Throughout, the opinion distinguishes valid administrative execution from impermissible lawmaking, rooting its analysis in Article I and the institutional logic of the constitutional framework.

Textualism plays a central but more targeted role, with 14 out of 20 points (15%). Kagan closely parses the language of §254—especially words like “sufficient,” “shall,” “consider,” “evolving,” and “affordable”—and uses dictionary definitions and statutory logic to clarify congressional intent. The opinion is attentive to the grammar and syntax of the statute, noting, for example, the legal significance of “shall consider” rather than “may,” and using the statutory text to dismantle the arguments made by the Fifth Circuit and respondents.

Pragmatism is an important secondary mode, at 12 out of 20 points (10%). The opinion foregrounds the real-world functionality of the universal service fund, the modest and predictable nature of FCC contributions, and the impracticality of the alternatives proposed by challengers. Kagan frames the FCC’s administration as both reasonable and effective, and she uses practical arguments to undermine the feasibility and logic of imposing numeric caps or other rigid requirements.

Historical practice supports the main doctrinal arguments, with 10 out of 20 points (8%). The opinion references the history of FCC subsidies, universal service doctrine, and the evolution of congressional delegations from the 1934 Communications Act through the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Kagan describes a “long tradition” of congressional authorization for agency discretion in rate-setting and related regulatory functions, using this tradition to bolster the Court’s comfort with the current statutory scheme.

Kagan methodically applies the nondelegation balancing approach developed through Whitman, Mistretta, American Power & Light, Panama Refining, and Schechter Poultry, showing that Congress’s guidance is constitutionally sufficient and that the FCC operates within those statutory parameters.

National ethos and moral reasoning are present but modest (5 out of 20 each). Kagan briefly invokes the principle of universal service as a national value—describing it as a commitment to a “more fully connected country”—and gestures toward congressional authority, institutional integrity, and democratic accountability. These values support but do not drive the legal analysis.

Originalism is not used (0/20); the opinion makes no reference to founding-era sources or original constitutional meaning.