Predicting the Outcomes of SCOTUS' October 2025 Case Argument Slate

How will the justices rule? We don't know but the tea leaves provide some strong insights.

Twenty years after the Supreme Court Forecasting Project showed that disciplined models can rival veteran Court watchers, this article applies a transparent method to the Court’s October docket. The aim is straightforward: identify the likely winner in each case.

The Supreme Court Forecasting Project opens with “The basic result is that the statistical model did better than the legal experts in forecasting the outcomes of the Term’s cases: The model predicted 75% of the Court’s affirm/reverse results correctly, while the experts collectively got 59.1% right.”

The modeling approach here is similar. It treats Martin–Quinn Scores (MQ) as the baseline map of the current Court and translates the October cases into that language using broad Supreme Court Database conventions. Some nuances in this article include that cases are sorted with a simple state-versus-federal split. Who prevailed below—coded as liberal or conservative for the topic (based on the Supreme Court Database Codebook)—provides the final bridge from judicial tendencies to a petitioner-or-respondent call.

The design is intentionally lean. A light calibration adjusts for stable, justice-specific quirks, and a single correlation step accounts for the Court’s tendency toward blocs, which yields realistic odds of unanimity or close splits without overfitting. The result is a set of case-by-case forecasts that are restrained in claims, clear about confidence, and grounded in the Court’s recent behavior.

The backbone: Martin–Quinn Scores (and why this model leans on it)

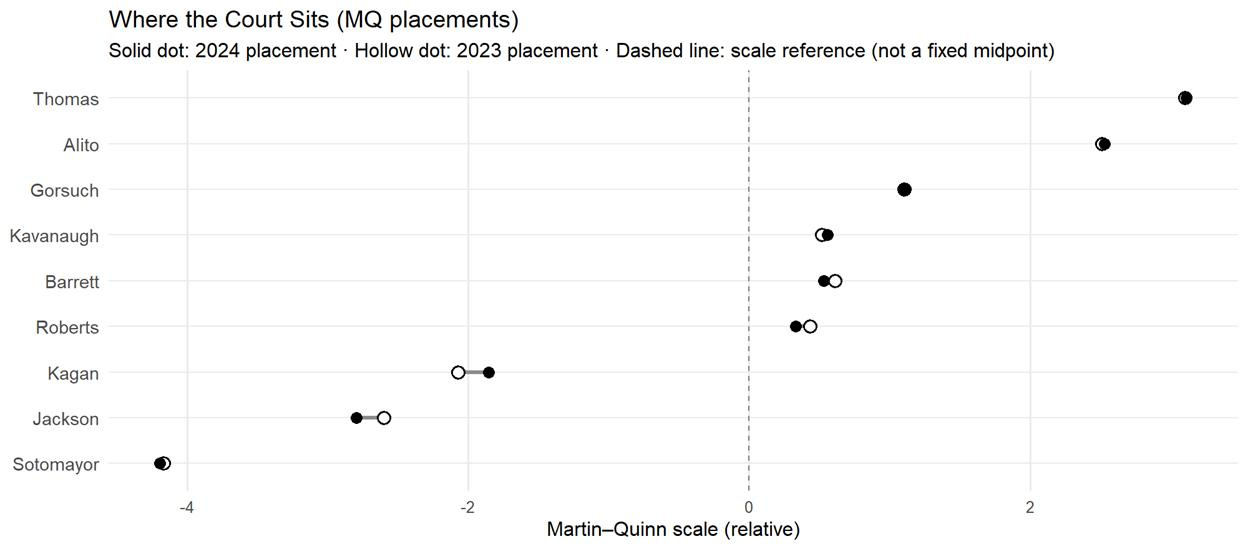

The article’s forecasting spine are MQ Scores—a set of term-by-term placements that locate each justice on a common ideological line by learning from how the Court has actually voted. It starts with the user setting the liberal and conservative ends of the spectrum and the seeks to find relative numbers of shared votes with the poles. The approach comes out of political methodology: a dynamic measurement model that updates with new terms and puts justices on a shared scale so their positions can be compared across time. The measures are sometimes criticized for minimizing the impact of case selection in how they compare across years and discount the shadow docket as sources of input for the justices’ ideological positions but they have proven robust predictors of case outcomes.

MQ Scores are useful here because they do one big job cleanly. They compress years of voting into a single, comparable position for each justice; moving modestly as the Court evolves; and traveling well across case types without demanding a thicket of case-specific assumptions. In other words, they provide a practical baseline for translating a justice’s long-run tendencies into a probability of siding with one party or the other.

This choice sits in a well-documented line of forecasting work. The Supreme Court Forecasting Project famously showed that a disciplined statistical model could outperform expert handicappers over an entire Term—an early sign that structured signals, applied consistently, could travel farther than intuition alone. A decade later, large-scale machine-learning efforts pushed coverage and automation even further, proving that relatively lean inputs could be scaled to long historical runs of cases and votes. And researchers have shown that boosted decision trees can squeeze out additional accuracy—useful evidence, even if the added complexity can make models harder to read at a glance.

Against that history, the article takes the MQ map as the anchor and layers only a few, transparent adjustments on top. The goal is a forecast that stays interpretable without giving up too much performance—a balance that suits a term preview better than a black-box sweep.

How the October cases are translated onto the MQ map

The article places each October case on the same ideological map that MQ provides for the justices. It does this with a small set of Supreme Court Database–style tags that capture the broad thrust of a dispute without pretending to resolve its finer points.

First, issue areas. Criminal-procedure matters and First Amendment disputes get their own lanes because the Court’s voting behavior reliably differs in those categories. Everything else is grouped as “other,” with a simple split for cases arriving from state courts versus federal courts. That’s enough structure to reflect real, term-over-term patterns without multiplying categories no model can defend at preview time.

Second, lower-court direction. Each case is labeled by who prevailed below and whether that outcome is conventionally coded liberal or conservative for that topic. In criminal cases, for example, a prosecution win is coded conservative; in speech cases, a speech-protective ruling is coded liberal. This single cue does the heavy lifting that links a justice’s long-run tendencies to a side of the caption—petitioner or respondent—in a way that’s consistent across the docket.

Third, just enough context. The model doesn’t chase sub-issues or doctrinal subcodes. Instead, it uses the lane and the lower-court direction as the backbone, then lets the nine justices’ MQ positions do the translation. As a practical matter, that means a case like Villarreal v. Texas (criminal procedure, state-court source, prosecution win below) is mapped differently from Chiles v. Salazar (First Amendment, speech-protective ruling below), and differently again from a federal tort or election-administration dispute in the “other” lane.

Case Capsules

1) Villarreal v. Texas (No. 24-557) — Sixth Amendment, attorney consultation during recess

Posture & parties. From the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. The petition contests a ruling involving whether a trial judge may bar a defendant from consulting with counsel about testimony during an overnight recess. The United States appears as amicus in support of Texas; argument was held Oct. 6, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Criminal Procedure. Litigants: state (respondent) vs. individual (petitioner). Source: state court. Lower-court winner & direction: Texas prevailed; for this topic a prosecution-side ruling is coded conservative for purposes of translating votes to petitioner/respondent probabilities.

2) Berk v. Choy (No. 24-440) — Erie & access-to-court: state affidavit-of-merit in federal court

Posture & parties. From the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. The question is whether a state rule requiring an expert affidavit with the complaint applies in federal court. Respondents (physician/hospital) prevailed below; argument is set for Oct. 6, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Federal Courts/Judicial Power (procedural/Erie). Litigants: private parties on both sides. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: defense win below treated conservative in this procedural-access setting (it heightens filing hurdles).

3) Barrett v. United States (No. 24-5774) — Double Jeopardy & dual penalties under §§ 924(c) and (j)

Posture & parties. From the Second Circuit. The case asks whether a single act can yield separate sentences under § 924(c) and § 924(j) without violating the Double Jeopardy Clause. The United States prevailed below; argument is set for Oct. 7, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model. Issue area:

Criminal Procedure (sentencing). Litigants: U.S. government vs. individual. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: government win coded conservative in this lane.

Chiles v. Salazar (No. 24-539) [updated]

Posture & parties. From the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. The case tests whether state restrictions on certain counselor–client conversations, framed by the parties as viewpoint-based limits, regulate professional conduct or restrict speech under the First Amendment. Oral argument is set for October 7, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: First Amendment (free speech). Litigants: individual challenger vs. state official. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: the state won below, which the model codes as a conservative outcome in a speech case (restriction upheld).

5) Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections (No. 24-568) — Standing to challenge state election rules

Posture & parties. From the Seventh Circuit. Federal candidates seek to challenge state time, place, and manner regulations; Illinois officials prevailed below. Argument is set for Oct. 8, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Federal Courts/Judicial Power (standing) with election-administration context. Litigants: candidates/party actors vs. state officials. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: government win treated conservative in this access/administration setting.

6) United States Postal Service v. Konan (No. 24-351) — FTCA “loss/miscarriage” exception & intentional nondelivery

Posture & parties. From the Fifth Circuit. The question is whether claims alleging intentional withholding of mail fall within the FTCA’s “loss” or “miscarriage” exceptions. USPS is the petitioner; argument is set for Oct. 8, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model. Issue area:

Private Law/Torts (FTCA liability). Litigants: U.S. agency vs. individual. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: plaintiff’s win below coded liberal in this tort-liability frame.

7) Bowe v. United States (No. 24-5438) — Successive collateral review: §§ 2244(b) and 2255

Posture & parties. From the Eleventh Circuit. The case addresses how successive motions to vacate are authorized and whether the Supreme Court can review authorization decisions. The United States prevailed below; argument is set for Oct. 14, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model. Issue area:

Criminal Procedure/Habeas. Litigants: U.S. government vs. individual. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: government win coded conservative in this lane.

8) Ellingburg v. United States (No. 24-482) — MVRA restitution and the Ex Post Facto Clause

Posture & parties. From the Eighth Circuit. The question is whether restitution under the Mandatory Victim Restitution Act is “penal” for Ex Post Facto purposes. The government prevailed below; argument is set for Oct. 14, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Criminal Procedure (sentencing). Litigants: U.S. government vs. individual. Source: federal court. Lower-court winner & direction: government win coded conservative.

9) Case v. Montana (No. 24-624) — Emergency-aid entry & the warrant requirement

Posture & parties. From the Montana Supreme Court. The dispute centers on whether officers may enter a home without a warrant on less than probable cause of an emergency, or whether the emergency-aid exception requires probable cause. Montana prevailed below; argument is set for Oct. 15, 2025.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Criminal Procedure/Fourth Amendment. Litigants: state vs. individual. Source: state court. Lower-court winner & direction: state win coded conservative for this topic.

10) Louisiana v. Callais (No. 24-109) — Redistricting & the VRA (reargument)

Posture & parties. Direct appeal from a three-judge district court in the Western District of Louisiana. Plaintiffs prevailed below; the Court noted probable jurisdiction, heard argument in March, restored the case for reargument, and set it for Oct. 15, 2025, with supplemental briefing on whether creating a second majority-minority district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments.

SCDB-style mapping for the model.

Issue area: Civil Rights (Voting/Redistricting). Litigants: state (appellant) vs. voters/civil-rights plaintiffs. Source: federal three-judge court. Lower-court winner & direction: plaintiffs’ win coded liberal in voting-rights/redistricting.

How the model was tested

The model was trained on earlier Terms, calibrated on 2020–2023, and then held to account on 2024—kept strictly out of sample. That split mirrors how a forecast is actually used: learn from the past, tune on the recent past, and judge performance on a term the model hasn’t seen.

Two scorecards governed every change. Case-level accuracy decided whether a feature earned its place; probabilistic calibration—checked with Brier/log-loss and reliability curves—ensured the numbers behaved like probabilities rather than confident guesses. If a tweak pushed accuracy up but bent the calibration curve out of shape, it didn’t stay. Group cut points were set the simple way: one threshold each for criminal procedure, First Amendment, and the “other” bucket (split by state vs. federal source), tuned on 2020–2023 and then locked before testing on 2024.

Additions were judged against a clean baseline: MQ translated to vote probabilities, then flipped into petitioner–respondent terms using the lower court’s direction. A candidate feature had to beat that baseline on 2024 and pass a justice-by-justice check—no wins that came at the expense of a marked dip for any one member of the Court. Sensitivity passes reran the test after toggling a handful of contested lower-court codings and with leave-one-term-out rotations across the tuning years to make sure any gains weren’t an accident.

Finally, vote-shape realism was kept separate from outcome calls. A single correlation parameter was calibrated to match the observed mix of unanimous, lopsided, and close decisions, but it did not influence who the model picked to win.

October forecasts: who’s favored, and whether the vote looks close

Below are case-by-case calls drawn from the model described above. Each capsule names the likely winner on whether the vote is more likely to be unanimous or split. The split note is directional—unanimous or lopsided versus close—not a hard count, and it reflects the model’s correlation step that captures how the Court tends to move in blocs.

Villarreal v. Texas (No. 24-557)

Likely winner: Villarreal (petitioner).

Why the model leans this way: A defendant’s right to confer with counsel during an overnight recess maps as a defendant-rights claim; Texas prevailed below. On this posture, the Court often corrects toward the counsel-rights side even when trial-management concerns are present.

Vote shape: Unanimous or lopsided more likely than truly close.

Berk v. Choy (No. 24-440)

Likely winner: Berk (petitioner).

Why: The affidavit-of-merit requirement traveling into federal court raises a familiar Erie-and-access question. With the defense win below and the issue framed as a filing hurdle, the model tilts toward a plaintiff-side correction in federal court.

Vote shape: Close (watch for a 6–3 or 5–4), given cross-cutting instincts on federal procedural uniformity.

Barrett v. United States (No. 24-5774)

Likely winner: United States (respondent).

Why: The question about separate sentences under §§ 924(c) and (j) reads as a government-side, charge-and-penalty issue, and the government prevailed below. The model’s history for similar sentencing questions points to affirmance.

Vote shape: Unanimous or lopsided is more likely than one-vote difference.

Chiles v. Salazar (No. 24-539)

Likely winner: Salazar (respondent).

Why: The Tenth Circuit upheld the state restriction, which the model codes as a conservative outcome in a First Amendment case. On review, the petitioner needs a speech-protective swing to reverse. Given the Court’s current center of gravity and the professional-conduct framing below, the edge runs to the state unless a workable limiting principle pulls the middle across.

Vote shape: Close—most plausibly a 6–3 or 5–4, depending on how the line between “professional conduct” and “speech” is drawn.

Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections (No. 24-568)

Likely winner: Illinois officials (respondents).

Why: Standing to challenge state time, place, and manner rules tends to be resolved conservatively when the plaintiffs’ theory is thin. State officials prevailed below; the model reads this as a likely affirmance.

Vote shape: Unanimous or lopsided more likely than a thin split.

United States Postal Service v. Konan (No. 24-351)

Likely winner: USPS (petitioner).

Why: The FTCA’s “loss or miscarriage of mail” carve-outs often favor the government when statutory text is read narrowly for liability. With the plaintiff’s win below, the model expects a correction.

Vote shape: Unanimous or lopsided more likely than close.

Bowe v. United States (No. 24-5438)

Likely winner: United States (respondent).

Why: Successive collateral-review mechanics generally favor restraint absent a clear statutory path the other way. The government prevailed below; the model points to affirmance.

Vote shape: Unanimous or lopsided more likely than close.

Ellingburg v. United States (No. 24-482)

Likely winner: United States (respondent).

Why: Whether MVRA restitution is “penal” for Ex Post Facto purposes is framed against a government win below. Similar sentencing-adjacent questions have leaned government-side in recent Terms.

Vote shape: Leans lopsided, with some chance of a close split depending on how the Justices frame “penal.”

Case v. Montana (No. 24-624)

Likely winner: Montana (respondent).

Why: The emergency-aid exception question arrives with a state-court affirmance of warrantless entry; the model reads that as a likely sustain, though the doctrinal line-drawing can invite separate writings.

Vote shape: Close more likely than truly unanimous.

Louisiana v. Callais (No. 24-109)

Likely winner: Callais (respondent/plaintiffs).

Why: The lower court required a second majority-minority district; voting-rights cases in this posture have drawn a conservative–liberal split but not always on strict party lines. The model gives the plaintiffs a modest edge.

Vote shape: Close—the docket history and stakes point to a divided Court.

What could shift these calls

By the time a case reaches oral argument, most chambers have a working view shaped by the briefs and internal memos. Oral argument rarely flips the ultimate winner. What it does change—often decisively—is how the Court gets there: narrow or broad, statutory or constitutional, and which justices can sign on to a common rationale. That’s why these forecasts function as pre-argument baselines. They mark where the Court is likely headed, while leaving room for argument to tighten or widen the margin.

The biggest mover when there is one is often the middle of the Court searching for a workable limiting principle. If counsel can offer a rule that is clear, administrable, and constrained by text or history, a case that looked close can gather votes and become lopsided. The Solicitor General’s position can also reshape the terrain, especially in statutory and criminal cases; a refined reading or a strategic concession can pull in justices who are otherwise skeptical.

Cases can also deflate on vehicle grounds. A jurisdictional snag, forfeiture, or a messy record can turn a sharp dispute into a narrow affirmance or a remand that attracts a broad coalition. In election and speech disputes, a focused path—resolving only what’s necessary—can turn a 5–4 forecast into something closer to 7–2. Conversely, when the legal choices are binary and the facts clean, margins tend to hold.

Category matters. Criminal-procedure questions often track steady patterns unless the government or petitioner offers a narrow rule that calibrates Fourth or Sixth Amendment stakes to practical policing or trial management. First Amendment cases are more volatile at argument; a persuasive account of line-drawing—how to distinguish speech from professional conduct, for example—can peel votes from unexpected places. Statutory cases like the FTCA and Erie disputes frequently hinge on text and structure; the justices’ comfort with a clean reading can turn a close call into a quiet, near-unanimous result.

The model already bakes in the Court’s tendency to move in blocs, which is why it reports whether a case is more likely unanimous or split.

Where does this leave us?

October sets the Court’s rhythm. This docket offers a familiar mix—criminal procedure, a sharp First Amendment test, a federal tort dispute with everyday reach, and an election case with national stakes. The model points to steady outcomes in several matters and flags a handful likely to divide the Court. If the pattern holds, expect a run of quiet, lopsided results on the margins and a few arguments that define the Term’s center of gravity.

Predictions though are a map, not a script. Counsel’s right to consult during an overnight recess, the contours of postal liability, the mechanics of successive collateral review—none are abstractions, and each turns on lines the Court can draw narrowly or broadly. The numbers here set expectations while the opinions will reveal how the justices choose to write the rule.

What to watch may not be only who wins, but how. A narrow path that gathers seven votes can say more about the Term than a 5–4 on broader ground. By the time October ends, the coalitions—and the direction of travel for the rest of the Term (and whether there are differences from previous Terms)—should be clearer.

To subscribe, share, or comment

Wow, on a roll! My sad pinhead is nearing implosion.

However, I note one category is “lower court direction” — recent shadow docket decisions, as well as Justice Thomas’s explanation last week, seems to indicate that precedence is just such a quaint idea. How does traditional analysis fare in the face of a changing Court?