SCOTUS Policy Implications: Berk v. Choy

Looking under the hood of a case that could impact the requirements for expert witnesses in federal court medical malpractice cases.

What it’s About

This case examines whether a state law requiring plaintiffs in medical malpractice cases to file a sworn affidavit from an expert witness as a condition of proceeding with the complaint—commonly known as an affidavit of merit (AOM)—must be applied in federal court in a diversity jurisdiction case.

Main Policy Areas

Federal Civil Procedure and Rulemaking Authority

Federalism and the Allocation of Judicial Power

State Tort Reform and Malpractice Litigation Policy

Access to Justice in Federal Courts

Judicial Uniformity and Forum Shopping

1. Current State of Policy

A. Federal and State Approaches to Affidavit of Merit (AOM) Statutes

Affidavit of merit (AOM) statutes are a procedural mechanism enacted by many states—Delaware among them—to address what legislatures perceive as a glut of meritless medical malpractice lawsuits. Under Delaware’s AOM statute, codified at Del. Code Ann. tit. 18, § 6853(a), a plaintiff must file an affidavit from a qualified medical expert along with their complaint attesting that there are reasonable grounds to believe the defendant committed negligence. Failure to file this affidavit, or to obtain a court-approved extension, results in the automatic rejection of the complaint by the court clerk.

The policy justification behind such statutes is clear: they aim to reduce litigation costs, deter frivolous claims, and protect healthcare providers from reputational harm and unwarranted settlement pressure. Delaware’s version of the AOM statute has been in effect since 1996, and courts in the state have treated it as a strict gatekeeping rule. See, e.g., Dishmon v. Fucci, 32 A.3d 338, 341 (Del. 2011); Dambro v. Meyer, 974 A.2d 121 (Del. 2009).

B. Treatment in Federal Courts: Diverging Circuit Approaches

The federal circuit courts are deeply divided on whether and when AOM statutes apply in federal court. This divergence results from the unsettled state of post-Shady Grove Erie jurisprudence.

The Third Circuit, where this case arises, has consistently held that AOM statutes like those in Pennsylvania and Delaware apply in diversity cases. In Liggon-Redding v. Estate of Sugarman, 659 F.3d 258 (3d Cir. 2011), the court reasoned that the AOM requirement “functions as a substantive condition of a cause of action under Pennsylvania law” and does not conflict with any Federal Rules. Applying the Hanna-Walker framework, the court found that no Federal Rule directly “answers the question” that the AOM statute addresses.

The Second Circuit, by contrast, took a different view in Corley v. United States, 11 F.4th 79 (2d Cir. 2021). There, the court found that Connecticut’s AOM law imposed an impermissible state procedural burden in a federal medical malpractice action. It emphasized that the Federal Rules already govern pleadings (Rules 8 and 11) and that allowing the state law to add an additional requirement would violate the principle set out in Hanna.

The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits have also generally leaned toward preemption, holding that various state AOM laws “answer the same question” as Federal Rules and thus conflict. See, e.g., Gallivan v. United States, 943 F.3d 291 (6th Cir. 2019); Martin v. Pierce County, 34 F.4th 1125 (9th Cir. 2022); Passmore v. Baylor Health Care Sys., 823 F.3d 292 (5th Cir. 2016).

In these circuits, federal courts refuse to enforce AOM statutes in diversity or FTCA cases, viewing them as procedural burdens inconsistent with the uniform requirements of the Federal Rules. This has led to a sharp split among federal courts—one that cuts directly to the heart of Erie doctrine's procedural-substantive boundary.

C. The Status Quo: Inconsistency and Strategic Forum Shopping

At present, the enforceability of an AOM statute in federal court depends heavily on geographic accident—i.e., where a lawsuit is filed. For example, a plaintiff filing a medical malpractice case against a Delaware doctor in the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware must file an AOM or face dismissal. The same claim, if filed in the Southern District of New York against a Connecticut doctor, would likely survive without such an affidavit.

This inconsistency encourages forum shopping and penalizes plaintiffs based on court selection rather than case merit. Moreover, it undermines predictability for litigants and erodes the goals of both state tort reformers and federal procedural uniformity.

D. Federal Rule Conflict and Erie’s Unstable Line

Federal courts continue to wrestle with the question of what counts as a “direct collision” with the Federal Rules. The Third Circuit argues that AOM statutes regulate state-created rights, not federal pleading practice. Other courts maintain that these statutes impermissibly impose new prerequisites to filing, which conflicts with the text and purpose of Rule 8(a) and Rule 11(b).

The analytical instability post-Shady Grove—especially the fractured opinions in that case—have left lower courts without clear guidance. Some emphasize the text of the Federal Rules (Shady Grove plurality); others emphasize the purpose of the state law and whether it is outcome-determinative (Shady Grove concurrence by Stevens). This fragmentation further fuels doctrinal unpredictability and intensifies the stakes in Berk v. Choy.

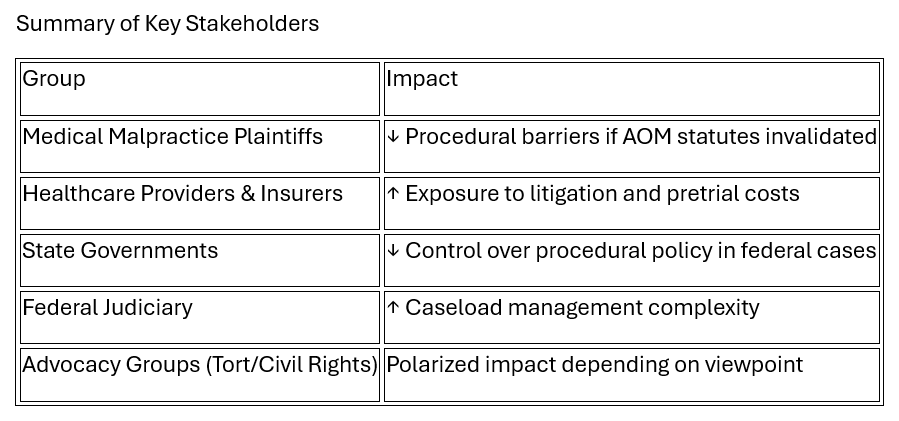

2. Impacted Groups

The Supreme Court’s resolution of the question in Berk v. Choy will affect a wide array of stakeholders across both the litigation landscape and healthcare system. The legal, procedural, and social stakes mean that the case's reach extends far beyond the parties themselves.

A. Medical Malpractice Plaintiffs

The most directly impacted group is plaintiffs in medical negligence lawsuits. Delaware’s affidavit of merit (AOM) requirement—and similar statutes in other states—raises the barrier to entry for filing malpractice claims by requiring plaintiffs to obtain a qualified expert before filing. This imposes not only a financial cost (expert review and drafting of an affidavit) but also a logistical and temporal burden.

In diversity cases in federal court, if AOM statutes are deemed inapplicable, plaintiffs would benefit from access to a forum with fewer pre-filing procedural hurdles. The outcome would significantly reduce the upfront cost of initiating a claim and lower the risk of immediate dismissal due to technical noncompliance. This particularly affects:

Low-income or self-represented litigants

Litigants in rural areas with limited access to specialized medical experts

Plaintiffs with meritorious but complex or novel malpractice claims

Statistically, malpractice claims are already difficult to win: a 2007 study by the New England Journal of Medicine found that only 27% of malpractice claims result in payment to plaintiffs, and those without expert backing are often dismissed early. Reducing AOM burdens could modestly shift this balance in favor of plaintiffs.

See: Studdert DM et al., “Claims, Errors, and Compensation Payments in Medical Malpractice Litigation,” N Engl J Med 354, no. 19 (2006).

B. Healthcare Providers and Medical Institutions

Physicians, hospitals, and insurers strongly support AOM statutes as part of a broader tort reform effort. These groups argue that early vetting via affidavits prevents nuisance suits and deters plaintiffs from initiating litigation without professional confirmation of negligence.

A Supreme Court ruling invalidating the application of AOM statutes in federal court would expose healthcare providers to increased procedural risk in diversity cases. Even if ultimate liability remains difficult to establish, the possibility of enduring a full federal litigation process (discovery, motion practice, possible trial) increases both cost and reputational exposure.

Medical professional associations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), have historically supported AOM-type reforms. In states without such statutes, or where they are unenforced in federal court, providers have reported higher litigation rates and broader variance in claim merit.

See: American Medical Association, “Medical Liability Reform NOW!”

C. State Governments and Legislatures

Delaware’s General Assembly, like many state legislatures, passed its AOM statute in response to rising malpractice insurance premiums and concerns about healthcare cost containment. The Delaware Supreme Court has treated § 6853 as a substantive policy judgment integral to its tort regime. See Dishmon v. Fucci, 32 A.3d 338 (Del. 2011).

Federal courts refusing to enforce AOM laws effectively override this state legislative judgment. That undermines state sovereignty in an area—tort law—that is traditionally a core domain of state lawmaking. States pursuing policy goals through medical liability reform would find those goals inconsistently respected depending on whether cases are heard in state or federal courts.

This creates disincentives for state innovation in procedural tort reform and may result in future legislative recalibration toward more clearly “substantive” statutory designs.

D. Federal Courts and the Judicial System

The outcome will affect case management burdens on federal courts. AOM statutes act as a screening device, filtering out claims before judges need to address them. If AOM statutes are unenforceable in federal courts, judges lose this filtering mechanism. That could result in:

Greater pretrial motion practice under Rules 12(b)(6) and 56

Increased need for court-appointed experts under Rule 706

Potential increases in volume of low-merit claims

However, federal courts already possess tools to deter frivolous litigation under Rule 11, and some critics argue that AOM statutes duplicate these safeguards while burdening good-faith litigants.

E. Tort Reform Advocates and Civil Rights Advocates

Tort reform proponents will view a decision invalidating AOM statutes in federal court as a setback to efforts aimed at limiting the scope and cost of litigation.

Civil rights and access-to-justice advocates will likely celebrate such a decision as protecting federal procedural uniformity and equalizing litigant access across jurisdictions.

The case is thus ideologically significant even though it turns on a technical procedural question.

3. Importance of Policy Area

The dispute in Berk v. Choy involves more than a technical civil procedure issue—it implicates core constitutional and institutional concerns at the heart of American legal federalism and judicial policymaking. The importance of the policy area can be analyzed across five key dimensions: federalism, civil access, procedural uniformity, tort reform, and judicial legitimacy.

A. Erie Doctrine and Judicial Federalism

At its core, this case tests the bounds of the Erie doctrine—one of the most enduring and contested principles of American judicial federalism. Established in Erie R.R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938), and elaborated in Hanna v. Plumer, 380 U.S. 460 (1965), the doctrine governs when federal courts sitting in diversity must apply state law versus when they may rely on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Erie is not merely procedural; it represents a structural compromise between dual sovereignty and national procedural uniformity. The outcome of this case could significantly alter how Erie is applied to pre-filing or pre-answer state procedural rules. A Supreme Court decision clarifying whether pre-filing conditions like affidavit-of-merit statutes are substantive or procedural for Erie purposes would provide critical guidance to lower courts, which currently apply divergent standards (see sections 1–2 above).

Scholars have called this issue “one of the most stubborn and consequential questions in federal civil litigation.” See Doernberg, “The Tempest: Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co.,” 44 Akron L. Rev. 1147 (2011)

B. Federal Rulemaking Authority under the Rules Enabling Act

This case also invites scrutiny of the Rules Enabling Act (REA), 28 U.S.C. § 2072, which provides the statutory authority for the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. A key issue is whether enforcing a state law that imposes an additional pleading burden (e.g., an expert affidavit) is permissible when the Federal Rules already set comprehensive pleading standards under Rule 8 and Rule 11.

If the Court finds that the state law “collides” with the Federal Rules, then under Hanna, the Rules trump—so long as they are valid under the REA. The outcome may therefore test the boundaries of REA interpretation and force the Court to clarify how to determine whether a Federal Rule truly “governs” the issue in dispute, as debated extensively in Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 559 U.S. 393 (2010).

C. Tort Reform and National Health Policy

Affidavit of merit statutes are a key component of state-level tort reform initiatives, particularly in medical malpractice law. These statutes are intended to reduce litigation costs and insurance premiums by discouraging baseless lawsuits. The potential invalidation of these statutes in federal courts undercuts their effect, as plaintiffs may increasingly choose federal forums to avoid state-imposed filing requirements.

Thus, this case also engages important questions about the ability of states to regulate healthcare-related litigation costs—an issue tied to the overall functionality of the U.S. healthcare system and medical liability market.

A decision invalidating AOM statutes in federal court could prompt new legislative responses, perhaps through substantive changes in state tort law or constitutional challenges to federal procedural supremacy.

D. Procedural Uniformity and Forum Shopping

The current state of federal jurisprudence has led to fragmentation. AOM statutes apply in federal court in some circuits but not others, depending on how those courts analyze Erie conflicts. This asymmetry results in:

Inconsistent access to remedies based solely on geography.

Incentives for plaintiffs to forum shop between state and federal courts.

Uncertainty for litigants and attorneys about pleading standards.

The Supreme Court’s resolution in Berk could restore nationwide procedural uniformity by clarifying how Federal Rules interact with state pre-filing statutes—reducing disparities and unpredictability in malpractice litigation.

See Benjamin Grossberg, “Uniformity, Federalism, and Tort Reform,” 159 U. Pa. L. Rev. 217 (2010).

E. Judicial Legitimacy and Doctrinal Clarity

Finally, the case is important because it offers the Court an opportunity to resolve a persistent doctrinal puzzle. Since Shady Grove, lower courts have applied various, sometimes contradictory, methodologies to determine whether a Federal Rule “controls” an issue under the REA and Erie. Without guidance, these doctrinal splits risk eroding the credibility and coherence of federal procedural jurisprudence.

By revisiting this issue, the Court can promote doctrinal coherence, reduce strategic litigation behavior, and reaffirm the balance of power between state legislatures and federal procedural authorities.

The policy area implicated in Berk v. Choy sits at the intersection of state procedural autonomy, federal judicial rulemaking, and access to justice. Its resolution will reverberate through multiple domains of litigation policy, including tort reform, judicial federalism, and the interpretation of the Rules Enabling Act. For these reasons, the case carries national significance well beyond its specific facts.

4. Movement of Precedent Over Time

The doctrine governing federal versus state procedural obligations in diversity jurisdiction has evolved incrementally since Erie v. Tompkins, with occasional bursts of doctrinal instability—most notably following Hanna v. Plumer and again in the aftermath of Shady Grove. The treatment of affidavit of merit (AOM) statutes fits squarely within this broader arc, reflecting both enduring tensions and evolving interpretive frameworks across federal courts.

A. From Erie to Hanna: Foundation and Framework

The Erie decision in 1938 was a revolutionary shift away from the idea that federal courts could create “general common law” in diversity cases. Erie established that in such cases, substantive rights and obligations are governed by state law, while federal courts retain authority over “procedural” rules. However, it offered only vague guidance on how to distinguish between the two.

In the decades that followed, the Court attempted to bring coherence to Erie’s substantive/procedural line. The most important doctrinal refinement came in Hanna v. Plumer (1965), which introduced the now-canonical two-part test:

If a Federal Rule “directly conflicts” with a state law, and is valid under the Rules Enabling Act, it governs.

If there is no direct conflict, Erie’s twin aims—discouraging forum shopping and avoiding inequitable administration of the laws—determine which rule applies.

Hanna marked a turning point in procedural federalism by formalizing a path for Federal Rules to override conflicting state procedural policies, while still recognizing the importance of state legal policy in outcome-determinative issues.

B. Walker and Byrd: Moderation and Nuance

Later cases like Walker v. Armco Steel Corp. (1980) and Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electric Cooperative (1958) added complexity. Walker emphasized the importance of asking whether the Federal Rule “answers the same question” as the state law. If not, Erie governs. Byrd introduced the idea that even when a state rule appears to regulate procedure, federal courts must weigh the countervailing federal interest in uniform court operations.

Together, these cases created a more nuanced balancing approach that courts have continued to struggle with, particularly when faced with hybrid state statutes like AOM laws that combine procedural form with substantive function.

C. The Fragmentation After Shady Grove

The next major disruption came with Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co. (2010). Although the case technically involved Rule 23 (class actions) and a New York statute that prohibited certain types of claims from being brought as class actions, its interpretive implications spilled over into other areas—especially hybrid procedural-substantive laws like AOM statutes.

The fractured Shady Grove decision left lower courts with conflicting interpretive options. The plurality opinion by Justice Scalia (joined by Roberts, Thomas, and Sotomayor) took a formalist view: if the Federal Rule covers the issue and is valid under the REA, it governs—even if the state law reflects substantive policy. Justice Stevens concurred in judgment but argued that courts must determine whether applying the Federal Rule would “abridge, enlarge, or modify” a substantive right under the REA. The four-justice dissent argued that state laws designed to regulate remedy availability should generally control in diversity cases.

This split injected new uncertainty into the Erie doctrine and has fueled a decade of divergence among the circuits.

D. Circuit-Level Disarray on AOM Statutes

In the years since Shady Grove, the circuits have adopted sharply divergent methodologies when addressing AOM statutes. Some treat them as non-conflicting with the Federal Rules and therefore enforceable (e.g., Third and Tenth Circuits), while others treat them as incompatible with federal pleading standards (e.g., Second, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits).

For example:

The Third Circuit’s Liggon-Redding decision applied the Erie-Hanna-Walker analysis to uphold Pennsylvania’s AOM statute in federal court, asserting no direct conflict with Federal Rules.

The Second Circuit’s Corley decision disagreed, finding that Connecticut’s statute conflicted with Rules 8 and 11.

As a result, federal plaintiffs with identical claims face different procedural obligations depending solely on geography.

E. Implications for Berk v. Choy

Berk v. Choy arrives at a pivotal moment in the evolution of procedural federalism. The Court has not revisited the core Erie-Hanna-Shady Grove conflict in over a decade. In the interim, lower courts have fractured, particularly on how to treat hybrid procedural-substantive state laws like AOM requirements.

This case gives the Court the opportunity to:

Reaffirm or recalibrate the Hanna “collision” test,

Clarify the scope and limits of Federal Rules under the Rules Enabling Act,

Establish a clearer method for assessing whether a state procedural rule substantively regulates the cause of action it applies to.

Over time, the procedural federalism landscape has become increasingly complicated, with no consensus on how to resolve collisions between Federal Rules and state procedural statutes that carry substantive effect. Berk v. Choy exemplifies this tension and offers the Court a vehicle to resolve it. The movement of precedent has oscillated between formalism and pragmatism, and the case demands a modern resolution to an enduring doctrinal fault line.

5. Supreme Court’s Treatment of Precedent

In assessing the likelihood that the Supreme Court would uphold or overturn the Third Circuit’s decision in Berk v. Choy, a key consideration is how the Court has historically treated—and may reinterpret—precedents in the Erie doctrine and related conflicts between state procedural statutes and Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court's treatment of these precedents has evolved in cycles of formalism, pragmatism, and fragmentation.

A. Consistent Deference to the Federal Rules’ Supremacy—When “On Point”

The Court has consistently upheld the validity of Federal Rules that directly address procedural issues, provided they comply with the Rules Enabling Act. In Hanna v. Plumer, the Court declared that if a Federal Rule “directly conflicts” with state law and is valid under the REA, the Federal Rule governs.

This position was reaffirmed in Sibbach v. Wilson & Co., 312 U.S. 1 (1941), and more recently in the plurality opinion in Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 559 U.S. 393 (2010). In both cases, the Court emphasized the supremacy of valid Federal Rules when they “answer the same question” as a state rule.

The Court has shown no appetite for invalidating Federal Rules under the REA and is unlikely to do so in Berk. Instead, the question will likely turn on whether the Federal Rules in question—likely Rules 8, 11, or 12—are deemed to cover the same procedural ground as Delaware’s AOM statute.

See Shady Grove, 559 U.S. at 398 (Scalia, J., plurality): “The test is not whether the rule affects a litigant’s substantive rights; most procedural rules do. What matters is what the rule regulates: If it governs only ‘the manner and the means’ by which the litigant’s rights are enforced, it is valid.”

B. Recognition of Substantive Interests in Procedural Forms

At the same time, the Court has occasionally tempered its procedural supremacy doctrine by recognizing when state procedural rules are so closely tied to substantive state policies that they merit deference. This view was most famously articulated by Justice Harlan in Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Elec. Coop., 356 U.S. 525 (1958), where the Court suggested that even outcome-determinative procedural rules might be displaced if strong federal interests in uniformity existed.

Justice Stevens’ concurrence in Shady Grove also carried forward this tradition by suggesting that courts should invalidate Federal Rules only when they abridge a substantive right, even if they technically govern procedure.

This line of thinking provides an avenue for the Court to distinguish Delaware’s AOM statute as more than procedural—it reflects a legislative choice to filter unmeritorious malpractice claims, arguably a substantive policy judgment in a medical liability regime.

Byrd v. Blue Ridge, 356 U.S. at 536–37: “The federal system is an independent system for administering justice to litigants who properly invoke its jurisdiction.”

C. Circuit Split Doctrine: A Motivating Factor for Clarification

The Supreme Court has historically treated circuit splits—especially those involving structural judicial doctrines like Erie—as prime candidates for certiorari. The persistent division among circuits on the enforceability of AOM statutes in federal court presents a textbook example of a doctrinal rift warranting resolution.

The Third Circuit (Liggon-Redding) and Tenth Circuit enforce AOM statutes in federal court.

The Second (Corley), Sixth (Gallivan), and Ninth Circuits reject their enforceability under the Federal Rules.

This split is not only wide but legally entrenched, as multiple circuits have reiterated their positions post-Shady Grove without reconciling their approaches. The Court’s past treatment of analogous conflicts—e.g., in Walker v. Armco Steel, 446 U.S. 740 (1980)—demonstrates its tendency to step in and resolve methodological fragmentation once it reaches a tipping point of unpredictability.

D. Shady Grove’s Legacy and Doctrinal Uncertainty

The Court’s fractured opinions in Shady Grove continue to cast a long shadow over Erie analysis. No single opinion commanded a majority, and lower courts have since split on whether to follow the plurality (Scalia), the concurrence (Stevens), or apply a blended outcome-based approach.

Given the confusion in Shady Grove’s wake, the Court may see Berk as an opportunity to:

Clarify the meaning of “direct conflict” under Hanna,

Resolve how to apply the REA’s “abridge, enlarge, or modify” limitation,

Reconcile diverging methodologies in Erie doctrine interpretation.

E. Practical Signals: Limited Reversals in Similar Contexts

In previous procedural Erie doctrine cases, the Court has generally not reversed lower courts that found no conflict between a Federal Rule and a state statute—unless the Federal Rule clearly displaced the state law. That pattern may favor the petitioner (Berk) here if the Court finds that Delaware’s AOM statute imposes a filing condition that Rule 8(a) and Rule 11 already regulate.

However, the Court’s deference to state tort reform efforts—especially in areas like medical malpractice—could tilt the balance if the justices view AOM statutes as fundamentally linked to state substantive policy.

The Supreme Court has historically treated Erie doctrine as a foundational but unsettled area of law. Its past treatment of precedent suggests a willingness to uphold Federal Rules that directly govern an issue, but also a sensitivity to state procedural innovations when they reflect substantive policy choices. In Berk v. Choy, the Court faces a mature circuit split and doctrinal uncertainty that squarely implicates the legacy of Shady Grove, the durability of Hanna, and the integrity of state tort reforms.

Whether the Court resolves the case by emphasizing procedural uniformity or by preserving state procedural experimentation may depend on how it frames the purpose and function of affidavit-of-merit statutes—as procedural tools or as gatekeepers to substantive liability.

6. Importance of Shifting Policy

The policy transformation at issue in Berk v. Choy is not merely technical; it holds the potential to reshape the balance of authority between state legislatures and federal courts in regulating the procedural aspects of tort litigation. The importance of this shift rests on how the Supreme Court chooses to characterize and treat state statutes like Delaware’s affidavit of merit (AOM) requirement within the broader framework of judicial federalism and procedural uniformity.

A. Affirming State AOM Statutes in Federal Court: Preserving Localized Tort Control

If the Supreme Court upholds the Third Circuit’s position—i.e., that Delaware’s AOM requirement does not conflict with the Federal Rules and must be applied in federal court—it would signal deference to states’ procedural autonomy within their substantive tort systems. This would effectively reinforce the ability of states to create procedural filters that shape access to the courtroom and the trajectory of medical malpractice claims, even when those claims are heard in federal forums.

Such a decision would underscore the principle that not all procedural rules are preempted by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and that state-designed procedural safeguards—especially those aimed at discouraging frivolous litigation—deserve some latitude under Erie.

This approach would likely encourage states to experiment with additional forms of procedural triage—such as early expert review panels, screening tribunals, or damages caps tied to procedural thresholds.

B. Striking Down State AOM Statutes in Federal Court: Restoring Procedural Uniformity

Alternatively, if the Court reverses the Third Circuit and holds that Delaware’s AOM statute “collides” with Federal Rules—most plausibly Rule 8 (general pleading), Rule 11 (certification of factual contentions), or Rule 12 (motions to dismiss)—it will reassert the uniform application of federal procedure and likely extinguish the enforceability of similar AOM statutes in federal court.

This would amount to a significant policy shift with nationwide implications. At least 29 states have some version of an AOM requirement or pre-suit certification process for medical malpractice or other professional negligence claims. If such rules are deemed incompatible with federal procedure, plaintiffs filing in federal court would no longer be bound by these gatekeeping requirements.

Such a ruling would encourage forum-shopping into federal court and increase litigation pressure on healthcare providers. It would also signal that the Supreme Court prioritizes the consistency and integrity of federal procedural rules over state-level efforts to calibrate access to litigation based on subject-matter sensitivity.

C. Implications for Future Erie Doctrine Litigation

Beyond tort law, this case may affect how courts treat a wide range of hybrid procedural statutes—including:

Pre-suit notice requirements

Certificate-of-review statutes in legal and architectural malpractice

Statutory waiting periods (e.g., for housing or civil rights claims)

Statutes mandating arbitration or alternative dispute resolution

A ruling that favors federal procedural uniformity may constrain states from embedding procedural safeguards within otherwise “substantive” areas of law. This would further entrench the primacy of Federal Rules in diversity cases and could provoke future legislative and judicial efforts to redefine the boundaries of state procedural authority.

D. Historical Echo: Revisiting the Shady Grove Aftermath

The fractured opinions in Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 559 U.S. 393 (2010) left lower courts uncertain about how to handle procedural state statutes that implicate substantive rights. Berk v. Choy provides a chance to shift policy by resolving whether such statutes should generally be upheld or struck down in federal court.

Depending on how the Court rules, the result could shift policy in favor of:

A more formalist, text-based test for Federal Rule supremacy (if the Court follows Scalia’s plurality),

A more contextual, substantive-rights-sensitive test (if it revives the Stevens concurrence or Ginsburg’s dissent),

Or a new framework that provides clearer direction for hybrid procedural rules like AOM requirements.

This would represent not only a significant doctrinal realignment, but also a shift in how federal courts conceptualize their procedural obligations to state policy.

E. Reputational and Administrative Consequences for the Judiciary

This case may also influence how courts perceive their role in balancing legal formalism with practical litigation realities. Striking a balance between judicial efficiency, respect for state legislatures, and fairness to litigants will have reputational consequences for the federal judiciary.

A ruling that imposes uniform procedural standards may simplify litigation administration and reduce fragmentation. A ruling that defers to state AOM laws may validate judicial gatekeeping efforts, but at the risk of procedural inconsistency and burdening federal judges with variable screening mechanisms across states.

The policy shift at stake in Berk v. Choy is of substantial legal, institutional, and ideological importance. It has the potential to reset the doctrine governing how far states may go in conditioning access to their tort systems—even when litigation takes place in federal court. Whether the Court reinforces state experimentation or reaffirms the supremacy of the Federal Rules, the result will affect both the architecture of procedural federalism and the strategic behavior of litigants across the nation.

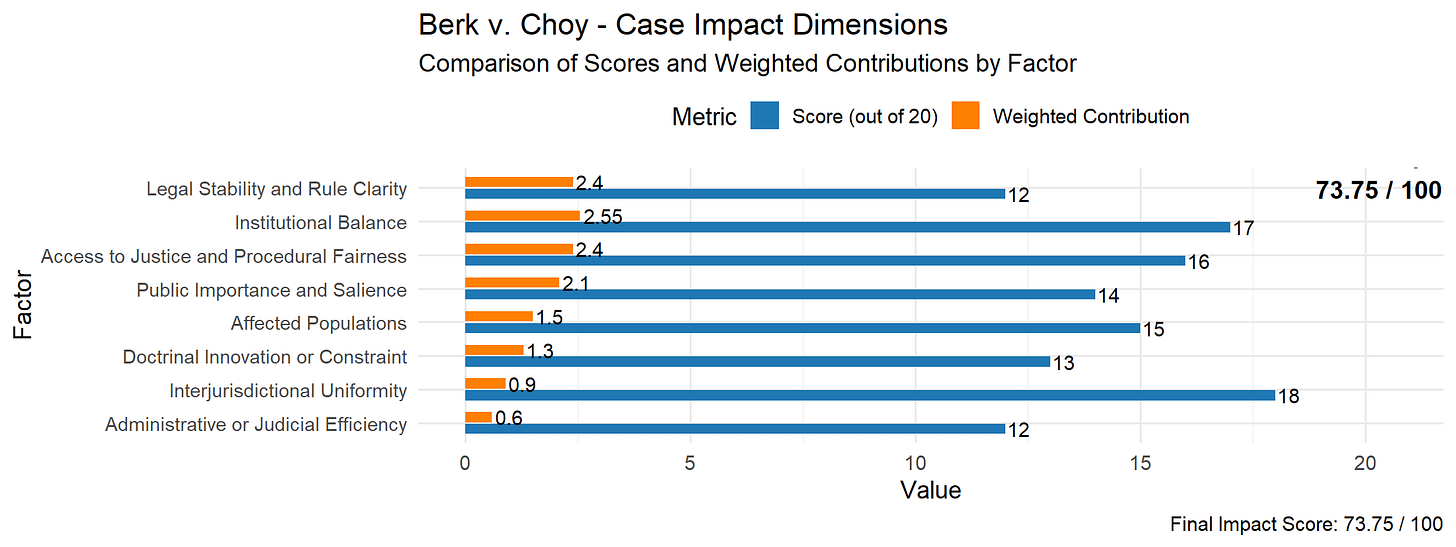

7. Spectrum-Based Policy Impact

This section evaluates the systemic policy impact of Berk v. Choy using an eight-factor scoring model. Each dimension is scored on a 1–20 scale and weighted based on its structural relevance to national legal doctrine, procedural coherence, and institutional governance. Narrative analyses accompany each category, incorporating both major decision paths: invalidating or upholding Delaware’s affidavit of merit (AOM) statute in federal court.

1. Legal Stability and Rule Clarity

Score: 12/20 | Weighted Contribution: 2.40

Berk v. Choy has the potential to clarify persistent doctrinal ambiguity in the Erie framework, particularly around the definition of “direct conflict” between state law and Federal Rules. A clear holding adopting one of the Shady Grove methodologies would enhance procedural predictability and provide guidance for future hybrid procedural-substantive disputes. However, the risk of a fractured or minimalist decision—similar to Shady Grove—limits the degree to which this case will conclusively stabilize the doctrine. A decision invalidating AOM statutes could improve national consistency but may also introduce new tensions with state tort regimes.

2. Institutional Balance

Score: 17/20 | Weighted Contribution: 2.55

The case involves a significant federalism issue. At stake is whether state legislatures can impose procedural thresholds, such as pre-filing affidavits, that operate within federal court systems. A ruling in favor of procedural preemption would reassert federal procedural supremacy and limit states' authority to modulate access to litigation. Conversely, upholding the statute would affirm that states can influence even federal court practice when regulating their own causes of action. The outcome will reshape the procedural sovereignty balance between federal courts and state legislative design.

3. Access to Justice and Procedural Fairness

Score: 16/20 | Weighted Contribution: 2.40

Affidavit of merit requirements impose financial and logistical burdens on plaintiffs, particularly in medical malpractice cases involving under-resourced individuals. Eliminating such statutes in federal court would reduce barriers to filing and expand equitable access. However, defenders argue that AOM statutes serve as effective screens against low-merit suits and help conserve judicial and professional resources. Either decision will carry significant implications for procedural fairness in the litigation process.

4. Public Importance and Salience

Score: 14/20 | Weighted Contribution: 2.10

While Berk v. Choy is not a headline-generating case, it is institutionally salient within the legal community. The case affects litigants, judges, medical professionals, bar associations, and rulemaking bodies. The decision will directly influence the design and enforcement of pre-suit procedural mechanisms in federal courts. It has also attracted attention from stakeholders such as the American Medical Association and legal aid organizations. The national relevance of its impact on tort reform and procedural federalism warrants elevated importance.

5. Affected Populations

Score: 15/20 | Weighted Contribution: 1.50

The populations most affected by the decision include malpractice plaintiffs, healthcare providers, and federal litigants subject to varying procedural regimes. Plaintiffs in states with AOM statutes face a greater burden accessing federal courts if such statutes are enforced. Conversely, providers and insurers rely on these statutes to manage litigation risk. The scope and asymmetry of the impact—especially on low-income and pro se plaintiffs—merit a substantial score.

6. Doctrinal Innovation or Constraint

Score: 13/20 | Weighted Contribution: 1.30

Berk v. Choy offers an opportunity to refine Erie doctrine post-Shady Grove, particularly with regard to the Rules Enabling Act and the test for procedural “collision.” The case is not expected to overrule prior precedent but may supply a unifying rationale or test that lower courts can apply consistently. A narrowly reasoned decision may constrain broader doctrinal applicability, whereas a decision resolving methodological inconsistencies could constitute moderate doctrinal innovation.

7. Interjurisdictional Uniformity

Score: 18/20 | Weighted Contribution: 0.90

A significant circuit split exists over the enforceability of AOM statutes in federal court. A clear decision in Berk would resolve divergent approaches among the Second, Third, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits. This unification is crucial in reducing procedural disparity across jurisdictions and improving federal court predictability in diversity cases involving state-imposed pre-filing conditions.

8. Administrative or Judicial Efficiency

Score: 12/20 | Weighted Contribution: 0.60

The efficiency implications are moderate. A decision invalidating AOM statutes may increase the volume of filed claims and reduce pre-screening in federal courts, thereby slightly increasing judicial burdens. On the other hand, enforcing such statutes adds complexity through motion practice over sufficiency, timeliness, and expert credentials. The efficiency impact is real but unlikely to transform federal docket management at a systemic level.

Final Impact Score: 73.75 / 100

This score reflects a high level of systemic policy significance. Berk v. Choy is likely to influence interjurisdictional uniformity, state-federal procedural boundaries, and access to justice in medical liability litigation. Although not revolutionary, the case offers the Court a critical opportunity to recalibrate procedural doctrine and institutional power sharing in an increasingly fragmented legal system.

8. Likely Court Position

Forecasting the likely position the Supreme Court will take in Berk v. Choy requires an integrated analysis of doctrinal commitments, ideological alignment, voting history on Erie doctrine, and the broader judicial posture of the current Court toward procedural formalism and state sovereignty. While the outcome is not certain, existing doctrinal cues and the justices' known jurisprudential leanings offer a strong basis for prediction.

A. Most Probable Holding

The Court is likely to reverse the Third Circuit and hold that Delaware’s affidavit of merit (AOM) statute does not apply in federal court under diversity jurisdiction. The prevailing rationale would be that the state statute directly conflicts with Federal Rules—particularly Rule 8 (pleading standard), Rule 11 (certification of good faith), and Rule 12 (grounds for dismissal)—and is therefore preempted under Hanna v. Plumer and the Rules Enabling Act.

This result would align with the interpretive method adopted by the Second, Fifth, Sixth, and Ninth Circuits, which treat AOM requirements as improperly imposing additional obligations on federal litigants at the complaint stage.

B. Supporting Doctrinal Signals

In Shady Grove, Justices Roberts, Alito, and Thomas formed part of the plurality that prioritized the Federal Rules' express scope over state procedure.

The Court has never invalidated a Federal Rule under the Rules Enabling Act, which strongly suggests that it will not read Rule 8 or 11 narrowly to accommodate Delaware’s statute.

Conservative justices have recently emphasized predictability and uniformity in procedural doctrine (e.g., in cases interpreting Rules 23 and 12).

See Shady Grove Orthopedic Assocs. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 559 U.S. 393, 398–400 (2010): https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/559/393/

C. Limiting or Concurring Opinions

There may be concurring opinions from Justices Gorsuch or Barrett expressing concern for preserving the states’ interest in structuring their civil justice systems, even while agreeing with the result under current doctrine. These concurrences could include a call for clearer guidance from the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules or Congress to adjust procedural asymmetries more directly.

Justice Kagan may also issue a narrower concurrence (as she did in cases involving class certification and arbitration) focused on preserving space for states to regulate litigation substantively without colliding with federal procedural norms.

D. Practical Outcome

If the Court rules in favor of Berk (i.e., that Delaware’s AOM statute does not apply), the ruling would:

Preclude enforcement of similar statutes in federal courts across at least 29 states,

Encourage more malpractice plaintiffs to file in federal court,

Increase pressure on Congress or the Judicial Conference to consider procedural harmonization reforms.

The Supreme Court’s likely position is to reverse and hold that the Federal Rules—particularly Rule 8—preempt Delaware’s AOM statute in federal court. This decision would be doctrinally conservative, institutionally clarifying, and procedurally significant. Although the decision may provoke dissents rooted in federalism and deference to state legislative policy, the dominant trend in the Court’s recent jurisprudence favors formal procedural uniformity and textual fidelity to the Federal Rules.

9. Policy Implications

A decision in Berk v. Choy will carry far-reaching policy consequences, both doctrinal and practical. It will not only reshape how state-level tort reform mechanisms operate in federal court, but also recalibrate procedural expectations for plaintiffs and defendants, influence litigation behavior, and redefine federal courts’ deference to hybrid state procedural-substantive laws.

A. Implications for Federalism and State Sovereignty

If the Court strikes down the Delaware affidavit of merit (AOM) requirement in federal court, the ruling will sharply delimit the procedural reach of state legislatures in diversity cases. It will communicate that even well-intentioned procedural tools—like AOM statutes designed to screen out meritless claims—are subordinate to the architecture and interpretive integrity of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

This will:

Undercut the practical effect of state tort reform initiatives in federal court;

Signal that federal courts will not adopt “procedural mirrors” of state rules absent clear doctrinal necessity;

Prompt states to consider recasting such statutes in more explicitly “substantive” terms (e.g., conditioning malpractice liability on procedural compliance).

It could also reignite federalism debates over procedural autonomy in state-designed causes of action, especially where access-to-justice and medical liability goals intersect.

B. Impact on Litigation Strategy and Forum Selection

A ruling that invalidates AOM statutes in federal court will create a procedural gap between state and federal forums. Plaintiffs who struggle to secure expert affidavits or who wish to delay expert engagement until after discovery will now have a strong incentive to file in federal court under diversity jurisdiction. This could:

Increase malpractice filings in federal district courts, especially in border states;

Compel defendants to seek remand more aggressively where removals occur;

Encourage tactical use of diversity jurisdiction to evade AOM gatekeeping.

This shift will heighten awareness of litigation strategy and forum selection rules (e.g., complete diversity, amount in controversy thresholds), particularly in states with rigorous malpractice procedural regimes.

C. Broader Implications for Rules Enabling Act Jurisprudence

Berk v. Choy may become a landmark for interpreting the Rules Enabling Act (REA). By clarifying when a Federal Rule “abridges, enlarges, or modifies” a substantive right—and thus exceeds its statutory authority—the decision could affect how courts assess other state procedural rules, such as:

Statutory waiting periods (e.g., employment or housing laws),

Mandatory mediation or arbitration procedures,

Pre-suit notice or certification requirements.

A strict preemption approach may prompt calls for procedural “federalism balancing,” or even inspire reform proposals to give federal judges discretion to honor certain state rules that closely regulate litigation policy.

D. Consequences for Access to Justice

Invalidating AOM statutes in federal court may improve access to litigation for low-income plaintiffs. Pre-filing expert certification can cost hundreds to thousands of dollars and often delays timely access to court. By removing this requirement in federal court, the decision could:

Level the playing field for plaintiffs who cannot immediately secure an expert,

Reduce front-end litigation costs,

Increase opportunities to investigate claims through discovery before obtaining full expert analysis.

However, this could also impose higher discovery and motion burdens on defendants, especially in cases that would otherwise have been screened out under an AOM regime.

E. Administrative Consequences for Federal Courts

Federal judges may face increased early-stage litigation management burdens. Without AOM statutes filtering out lower-merit claims, more malpractice suits may reach the motion-to-dismiss or discovery stages, requiring:

More Rule 12(b)(6) litigation,

Earlier use of Daubert motions and Rule 702 gatekeeping,

Greater reliance on case screening through judicially managed scheduling.

Some judges may respond by invoking Rule 11 more assertively or by issuing standing orders to require preliminary expert disclosures, functionally recreating some AOM features via local rule.

F. Ripple Effects in Professional Liability and Regulatory Fields

Although Berk focuses on medical malpractice, the Court’s reasoning will influence other professional negligence arenas, including:

Legal malpractice (some states require certificates of merit),

Engineering, architecture, and accounting liability,

Financial regulatory violations (e.g., securities certifications).

The logic of preempting AOM statutes may reduce the enforceability of any state procedural law that creates pre-filing hurdles unless Congress affirmatively adopts such a rule or amends the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to accommodate it.

Berk v. Choy will have consequences far beyond Delaware. Whether the Court embraces procedural uniformity or defers to state legislative judgments, its decision will reset expectations for how far states may go in regulating litigation process—even in federal court. The ruling will resonate in doctrinal debates over Erie, policy discussions about forum shopping, and practical questions of how federal courts can manage the front end of complex civil litigation in a manner that balances justice, efficiency, and deference to state law.

I’d like to thank Vikram Narasimhan for helping with research for this article

Didn't Gorsuch write Virginia Uranium? That case seems to move away from a conflict preemption analysis to say that the FRCP occupy the "field."

Another intriguing journey—admirably studying a problem I didn’t know existed.