Supreme Court Cert Report December 2024 [Deep Dive #3]

A look under the hood at the major players getting cases before the justices

* Note: This is a longer post and so you may need to click on the web version if the e-mail limits the post length. The tables can only be expanded in the web version as well.

What does the certiorari landscape look like in 2024? To get there it is important to know the roots of certiorari and why this is the method by which the justices take cases. The writ of certiorari (cert) goes back well over a century. In an 1891 article for the journal Political Science Quarterly, Frank Goodnow wrote,

“The better rule at the present time, as derived from these decisions, is that the province of the writ of certiorari is to quash the decision of a subordinate administrative tribunal: first, because it has exceeded its jurisdiction; second, because it has not followed the formalities required by law; and third, because it has made an error in the application of a principle of law to the case at bar -among which errors of law is to be included the finding of a fact unsupported by evidence. And to the end that the court of review may decide these points, it is necessary that the lower court send up in addition to the mere record all facts which are material, especially the evidence.”

Goodnow described in the 19th century that certiorari “…in our country, the chief means by which the courts review administrative action…” Since then, certiorari has taken on an even greater life as in 1925 and then augmented in 1988 Congress gave the Court near full discretion over its merits docket by removing almost all mandatory appeals to the Court.

Although there are no rules that force the Court to grant cert in particular cases, in conformance with Supreme Court Rule 10 (not really much beyond a rule of thumb), conflicts in decisions between two circuit courts of appeals are typically the main reason the justices take cases, although there are plenty of cases that they take without clear circuit splits.

Below are various metrics tracking cert over the past calendar year looking at the paid cases (as opposed to those filed by indigents, known as IFP cases, where Court fees are waived) and individuals and entities involved in the appellate litigation. Some of the raw data related to these petitions is also provided below.

A Veritable Who’s Who of Supreme Court Advocates

The names on successful petitions often are repeat Supreme Court players. That is no coincidence. Sophisticated advocates know what cases get the justices’ attention in particular times and know what they can and need to do to augment the natural impact of an important case’s facts, law, and procedural history. This may may be garnering support from amici (friends of the court), deciding how to draft petitions for cert, or it might just be signing the petition itself.

In 2005, the same year he was appointed Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, John Roberts wrote for the Journal of Supreme Court History,

“…whatever the reasons, the sharp decline in the number of opportunities for lawyers to argue before the Court has been accompanied, perhaps paradoxically or perhaps not, by an even more dramatic rise in the number of experienced Supreme Court advocates appearing before the Court, both in absolute terms and proportionately.”

On an empirical level, I along with a co-author wrote in a 2017 paper (which was the largest cert dataset in a published study at the time), “Accumulated practice before the Supreme Court allows attorneys to develop specialized knowledge of the Justices and their specific predilections, as well as relationships with the Justices that other attorneys lack. Exposure to the Court also provides attorneys with insight into what to include and exclude from their petitions. This includes what the Court might find useful and, consequently, the type of material that will draw attention on cert. Many experienced Supreme Court attorneys also clerked for Supreme Court Justices, an experience that provides them with intimate knowledge of Justices that others lack.”

Many of the attorneys we discussed in the article are still successful at Supreme Court cert today.

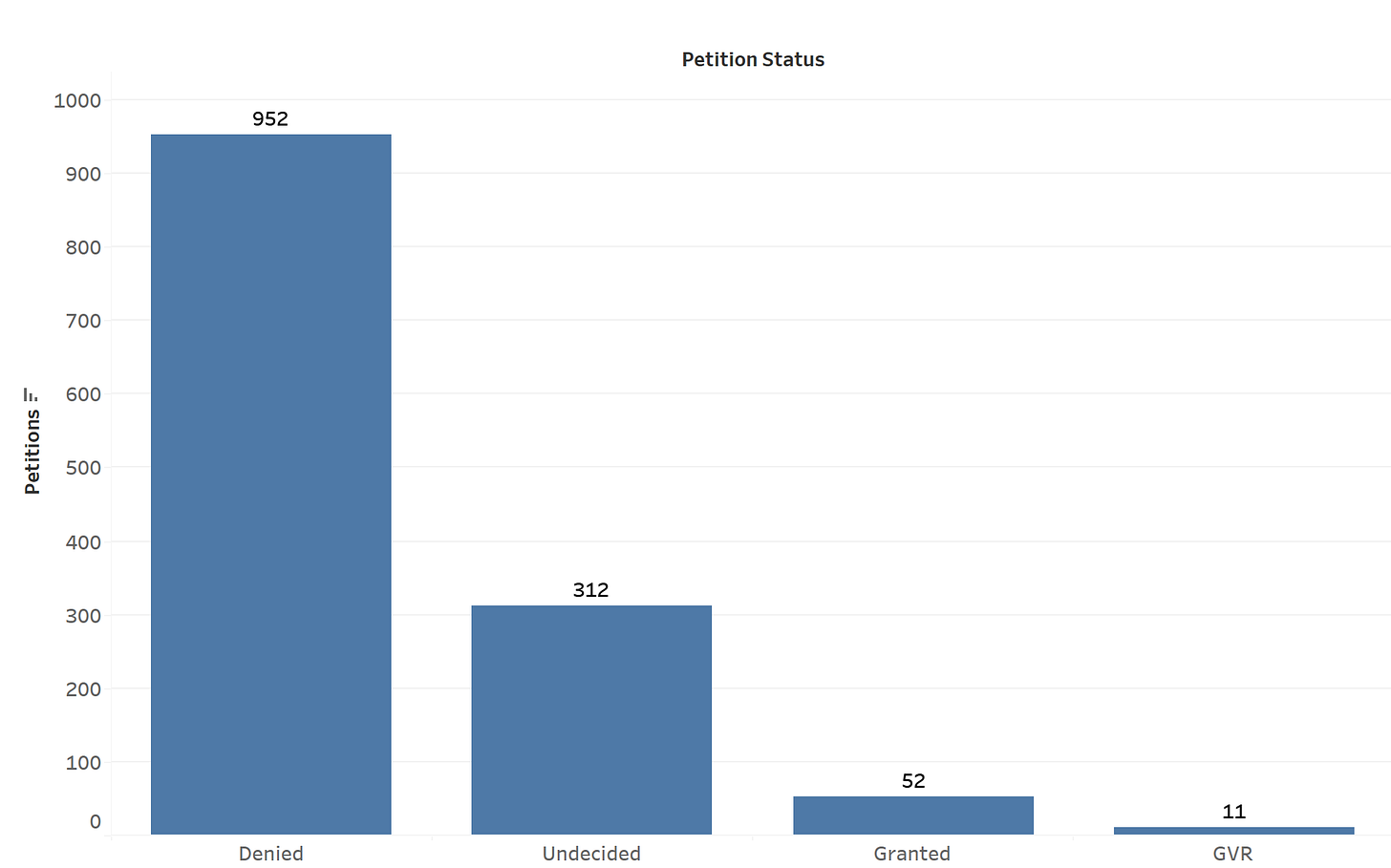

Below are data from 1,327 cert petitions filed from the beginning of 2024 through December 19, 2024. The aspects I examined in each case are case name, docket date, docket number, cert amicus count, merits amicus count, lower court, petition status, and attorneys and firms on the merits.

First a look at the 52 granted petitions.

These data which exclude GVRs (cases that were granted on cert, vacated, and remanded based on other decisions and therefore not argued on the merits) confirm the assumption of the success of repeat players. The only attorney outside of the OSG with more than two grants from petitions filed during this period is Jeffrey Fisher who was also one of the most successful attorneys we found in the 2017 paper. Former S.G. Noel Francisco was another attorney with multiple successful petitions along with former Acting S.G. Neal Katyal, as were Supreme Court veterans Misha Tseytlin, Helgi Walker, and Aaron Streett.

Moving to attorneys with a single grant we see many other successful repeat players such as Paul Clement, Kannon Shanmugam, and Deepak Gupta. Mainly correlated with these petitioners’ success, the non-OSG groups with the most grants include Hogan Lovells and Gibson Dunn with four, along with O’Melveny Myers, Troutman Pepper, Jones Day, and several others with multiple grants.

The granted cases only tell part of the story though. 312 petitions are still undecided.

Different attorneys have varying levels of success in attracting amici which on cert petitions often are seen as important signals to the justices. There are several building blocks to work through before reaching the previously mentioned two points though.