The $133 Billion Question: Inside the Supreme Court’s Historic Tariff Case

Ninety-one days after oral arguments, the justices still haven’t ruled. The delay itself tells a story about the complexity of constraining presidential power in the age of emergency authority.

By most accounts, November 5, 2025 was a rough day for the federal government at the Supreme Court. Over two hours of oral argument in V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. United States, Justice Department deputies faced withering skepticism from across the ideological spectrum about whether President Trump could impose sweeping tariffs by declaring a national emergency under a 1977 statute that never mentions tariffs.

Ninety-one days later, there’s still no decision. This article uses qualitative and quantitative methodologies to try to make sense of the current morass. That includes looking at historical decision timings, previously accelerated case schedules, the impact of case complexity, and more in an attempt to assess what is holding up a decision in the case, possible outcomes, and the downstream impact of the Supreme Court decision.

The delay has become as significant as the case itself. At stake is more than $133 billion in collected tariffs—it’s the constitutional architecture of who decides when and how Americans are taxed, the limits of presidential emergency powers, and whether the major questions doctrine that has reshaped administrative law over the past five years extends to foreign affairs and national security.

The lower courts spoke with unusual unanimity. The Court of International Trade struck down all the tariffs in May 2025, and the Federal Circuit affirmed en banc in August. Both courts found that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), which authorizes the President to “regulate... importation” during emergencies, doesn’t include the power to impose unlimited tariffs—especially not $133 billion worth without clear congressional authorization. As the CIT put it, “regulate importation” means controlling whether and how goods enter the country, not the power to tax them at rates set by presidential discretion.

But the oral arguments revealed unexpected doctrinal complexity. While six to nine justices appeared skeptical of the government’s position, the questioning also exposed genuine disagreement about first-order questions: Does the major questions doctrine apply when the President invokes foreign affairs or national security rationales? Where’s the line between “episodic” emergency responses (which courts may defer to) and “systematic” restructuring of trade policy (which requires congressional authorization)? And if the Court strikes down these tariffs, what happens to the $133 billion already collected—does the Constitution require refunds, or can the government keep money collected under a law later held unconstitutional?

While the Supreme Court deliberates, customs liquidation deadlines are passing right now. Under historical provisions of customs law, companies that miss their protest deadlines—even by a single day—are permanently barred from obtaining refunds, even if the Supreme Court ultimately rules the tariffs unconstitutional. That reality has sparked an explosion of protective litigation in the Court of International Trade. At least 108 companies have filed consolidated suits in just one lead case, with the Justice Department estimating “thousands” more to come. The parade of plaintiffs reads like a cross-section of the American economy: Costco (racing against a December 15 liquidation deadline), Toyota, Bumble Bee Foods, Yokohama Tire, Revlon, Alcoa, and dozens of others ranging from Fortune 500 corporations to small manufacturers.

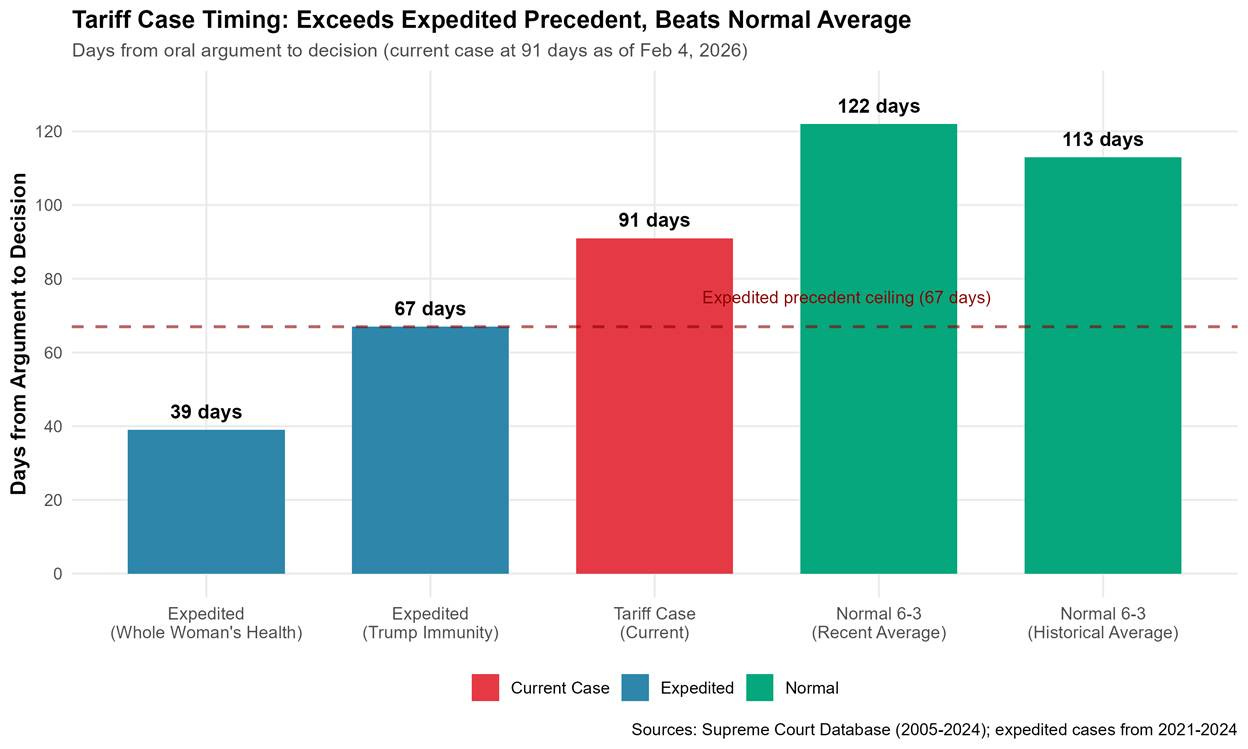

The timing of the Supreme Court’s deliberation—now at 91 days and counting—offers clues about what’s happening behind the red velvet curtain. Historical data on Supreme Court decision times reveals patterns: Expedited cases typically decide in 39 to 67 days. At 91 days, this case has exceeded that range by 24 to 52 days. Yet it remains faster than the 113-day average for normal divided decisions. The timing suggests a Court wrestling with doctrinal complexity, likely producing multiple opinions, and possibly negotiating to build a broader coalition than the 6-3 that oral arguments suggested.

Then there’s the government’s public messaging. A February 3, 2026 Reuters article—88 days after oral arguments—provided an unique instance where U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer offered a public comment on the case. Speaking to CNBC, he explained the delay by pointing to “enormous” stakes and suggested the challenge to Trump’s tariffs was not “an open and shut case.” His framing raised immediate questions: Was this genuine confidence that internal Court dynamics had shifted in the government’s favor? Or was it preemptive narrative-shaping, preparing the public for a loss by characterizing it as a close legal question where the government had strong arguments?

This article examines what happened at oral arguments, what historical timing patterns reveal about the Court’s deliberations, and what happens to the $133 billion whether the government wins or loses. The answer to that last question is more complicated—and takes far longer—than most observers realize. Even companies that prevail in the Supreme Court face a two-to-three-year administrative process through the Court of International Trade to actually receive refunds. And companies that missed their protest deadlines may never see their money again, regardless of the Supreme Court’s ultimate ruling.

This is a long one as it covers many angles of this case, from the lower courts prior decisions and possible remedies on remand to the Supreme Court’s process and why it is taking much longer than expected, so buckle up.

The Constitutional Challenge

First, the ultra vires claim: The challengers argued that IEEPA’s authorization to “regulate... importation” simply doesn’t include the power to impose tariffs or set duty rates. This was fundamentally a statutory interpretation question. When Congress wants to delegate tariff-setting authority, it knows how to do so explicitly—it used precise language in Section 232 (”adjust imports” through “duties or other import restrictions”) and Section 301 (authority to impose “duties” or “restrictions on imports”). The absence of such language in IEEPA, enacted after those statutes, strongly suggested Congress didn’t intend IEEPA to authorize what those other statutes explicitly permitted.

According to arguments in the case, the legislative history reinforced this interpretation. IEEPA was enacted in 1977 specifically to narrow presidential emergency powers. Congress was responding to concerns that TWEA, enacted during World War I, had become a vehicle for expansive presidential economic regulation during peacetime. The Senate report accompanying IEEPA emphasized that the new statute was meant to establish “clear standards” and provide “better accountability” for emergency powers. Reading IEEPA to authorize unlimited tariffs would transform it from a constraint on presidential power into an unprecedented expansion—exactly the opposite of Congress’s stated intent.

Second, the “deal with” requirement: Even if IEEPA could theoretically authorize some tariffs in some circumstances, the challengers argued these particular tariffs failed IEEPA’s requirement that emergency actions must “deal with” the declared threat. Broad-based tariffs on all imports from Mexico don’t target drug trafficking operations—they’re equally applied to legitimate commerce in automobiles, avocados, and aluminum. Reciprocal tariffs calculated based on trade statistics bear no relationship whatsoever to fentanyl interdiction. The government’s theory would allow the President to declare an emergency on any subject and then take any economic action affecting any foreign country, regardless of whether that action actually addressed the declared emergency.

Third, the nondelegation doctrine: The challengers argued that even if IEEPA’s text could be stretched to authorize tariffs, such a reading would raise grave constitutional problems. The nondelegation doctrine, rooted in Article I’s vesting of legislative power in Congress, prohibits Congress from delegating core legislative functions without providing an “intelligible principle” to guide and constrain executive discretion. If IEEPA authorizes the President to impose tariffs of any amount on any goods from any country simply by declaring an emergency, it gives the executive a blank check to exercise the taxing power—one of the Constitution’s most fundamental legislative functions. As the Court of International Trade put it, such a reading would raise “grave questions” under the nondelegation doctrine that courts should avoid if the statutory text permits a narrower construction.

Fourth, the major questions doctrine: Even if IEEPA’s text were ambiguous, the challengers invoked the major questions doctrine—the interpretive presumption that courts should not assume Congress delegates decisions of “vast economic and political significance” through vague or ancillary provisions. The Supreme Court has applied this doctrine with increasing frequency over the past five years, striking down or narrowing agency assertions of authority in contexts ranging from the CDC’s eviction moratorium to OSHA’s vaccine mandate to the EPA’s climate regulations. Here, the government was claiming authority to collect $133 billion in tariffs affecting hundreds of billions of dollars in annual trade based on a single word—”regulate”—in a statute that never mentions tariffs. If that isn’t a “major question” requiring clear congressional authorization, it’s hard to imagine what would be.

The Lower Courts: Two Unanimous Rejections

The Court of International Trade heard the consolidated cases and issued its decision on May 28, 2025. Writing for a unanimous three-judge panel, Judge Jane Restani systematically rejected each of the government’s arguments.

On the statutory question, the court held that “regulate... importation” simply doesn’t encompass the power to impose tariffs:

“The government asks this Court to interpret ‘regulate’ as encompassing the power to impose duties and set tariff rates—powers that the Constitution explicitly vests in Congress. We decline to attribute to Congress an intent to delegate such sweeping authority based on a single word that has never been understood to carry such weight. ‘Regulate importation’ means to control the terms and conditions under which goods may enter the country—licenses, quotas, prohibitions. It does not mean the power to tax those goods at rates set by executive discretion.”

The court found this reading confirmed by statutory structure and history. IEEPA contains detailed procedural requirements—emergency declarations, reporting obligations, congressional oversight mechanisms—but zero substantive limits on tariff rates or amounts. If Congress had intended to delegate the taxing power, one would expect to see substantive constraints: rate caps, proportionality requirements, durational limits. The absence of such constraints suggested Congress never contemplated authorizing tariffs at all.

The court also found that the 1977 enactment date was significant. Congress passed IEEPA after several decades of trade-specific statutes that explicitly authorized presidential tariff actions. The absence of similar language in IEEPA—a statute specifically designed to narrow presidential emergency authority—strongly suggested that Congress deliberately excluded tariffs from IEEPA’s scope.

On the “deal with” test, the court found that broad-based tariffs on all Mexican imports failed any meaningful nexus requirement:

“Universal tariffs on tomatoes and Toyota trucks do not ‘deal with’ drug trafficking in any coherent sense. They burden all commerce equally, affecting law-abiding businesses that have no connection to illicit drug trade. The government’s theory would allow the President to declare an emergency on any subject and then regulate any economic activity affecting any foreign country, rendering the ‘deal with’ requirement a nullity.”

The court noted that while IEEPA gives the President flexibility in choosing how to address emergencies, that flexibility isn’t unlimited. Actions must bear some rational relationship to the declared threat. Here, tariffs functioning primarily as revenue-raising measures or trade negotiation tools simply didn’t address drug trafficking.

On constitutional avoidance, the court found that reading IEEPA to authorize unlimited tariffs would raise grave nondelegation concerns. Under J.W. Hampton’s intelligible principle test, Congress must provide standards to guide and constrain executive discretion. But if “regulate importation” means “impose tariffs of any amount on any goods,” what constraint remains? The government’s only answer was that the President must declare an emergency first—but the President determines what constitutes an emergency, making this a circular non-constraint.

Finally, the court applied the major questions doctrine. Collecting $133 billion in tariffs affecting fundamental aspects of international trade is precisely the kind of decision of “vast economic and political significance” that requires clear congressional authorization. The single word “regulate” in a statute that never mentions tariffs, duties, or rates couldn’t satisfy that clear-statement requirement.

The government appealed to the Federal Circuit, which hears appeals from the Court of International Trade. On August 29, 2025, sitting en banc with all active judges participating, the Federal Circuit affirmed in a decisive opinion. The appellate court agreed with the CIT’s analysis on every major point.

The Federal Circuit’s opinion added an important discussion of Yoshida International, Inc. v. United States, a 1974 decision by the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (the Federal Circuit’s predecessor) that the government relied on heavily. In Yoshida, that court had upheld President Nixon’s 10% supplemental tariff imposed under TWEA during the 1971 dollar crisis. The Federal Circuit distinguished Yoshida on multiple grounds:

TWEA was broader than IEEPA, containing language authorizing regulation of “any... transactions” (not just “importation”)

Nixon’s tariff was explicitly temporary, capped at 10%, and limited by existing statutory tariff rates

Yoshida itself had cautioned that unlimited tariff authority would raise constitutional problems

Most importantly, Congress enacted IEEPA in 1977 specifically to narrow the presidential powers that TWEA (and cases like Yoshida) had approved

“Far from supporting the government’s position,” the Federal Circuit wrote, “Yoshida confirms that even under the broader TWEA, unlimited tariff authority raised concerns that led Congress to enact the more restrictive IEEPA.”

With two unanimous lower court decisions striking down all IEEPA-based tariffs, the government petitioned the Supreme Court for review. And on September 9, 2025, the Court not only granted certiorari but also granted the government’s motion for expedited consideration—a rare procedural step signaling recognition that the case presented urgent, ongoing harm requiring prompt resolution.

II. SCOTUS ORAL ARGUMENTS: THE DOCTRINE COLLIDES WITH REALITY

The Government’s Opening and Immediate Pushback

The oral arguments on November 5, 2025, revealed a Court grappling with fundamental questions about the separation of powers, presidential authority in emergencies, and how recent developments in administrative law doctrine apply to foreign affairs and national security. Principal Deputy Solicitor General Joshua opened for the government, emphasizing IEEPA’s text and the President’s need for flexibility in responding to national emergencies.

Early in the arguments Chief Justice Roberts interrupted with the question that would frame much of the argument. Roberts presses on what he sees as a selective reading of precedent. cites Dames & Moore to argue for broad judicial deference to presidential emergency actions in foreign affairs, but tries to sidestep Algonquin—a limiting case—by labeling it “domestic.” Roberts calls that move circular: you can’t get deference just by classifying the issue as foreign affairs if the underlying question is still statutory authority.

Roberts then sharpens the point into a doctrinal constraint: even in an emergency, the President’s power is limited by what Congress actually granted, and Algonquin’s principle—“a national emergency does not enlarge the statutory grant of power”—should still apply. In other words, “foreign affairs” may affect the posture (maybe more caution or deference), but it doesn’t erase statutory limits or let the executive bypass restrictive precedent just by rebranding the context.

This exchange helped set the tone. Roberts appeared skeptical of the government’s effort to invoke broad foreign affairs deference while distinguishing cases that constrained emergency authority. The Chief Justice’s concern—that the government wanted deference from some precedents while avoiding constraints from others simply by manipulating labels—would resurface throughout the arguments.

The Yoshida Problem: When Your Precedent Cuts Against You

One of the government’s central arguments rested on Yoshida International, the 1975 case upholding Nixon’s temporary 10% tariff surcharge. The government argued that if TWEA’s authorization to regulate “transactions” included tariff authority, IEEPA’s parallel authorization to regulate “importation” should be interpreted the same way.

Several Justices treated the government’s reading of IEEPA as implying extraordinarily broad tariff authority and pressed what, if anything, would constrain it. One line of questioning framed the issue as a major-questions problem: the government was relying on statutory language that had not previously been used to justify tariffs, yet the theory would allow tariffs on any product from any country, in any amount, for any length of time. Another line of questioning emphasized the practical stakes of delay, noting that tariffs could continue to be collected while challenges work their way through the courts, with the sums at issue already in the hundreds of billions and potentially far higher. And when the government invoked Nixon-era practice and Yoshida to support its position, the Court’s questions highlighted that even Yoshida described meaningful limits—rejecting the idea that the President may fix tariff rates at will without regard to congressionally prescribed rates and pointing to statutory guardrails elsewhere in the trade framework. Finally, Justice Gorsuch focused on the statutory text, pressing whether—given that the statute authorizes regulation “by means of licenses or otherwise” and the parties acknowledged that licensing can be economically equivalent to a tariff—tariffs should be understood as an available “means,” and if not, what limiting principle in the statute supplies the boundary.

Roberts and the “Episodic” Versus “Systematic” Distinction

Perhaps the most doctrinally significant exchange came when Chief Justice Roberts distinguished Dames & Moore v. Regan—the 1981 case that had upheld President Carter’s settlement with Iran under IEEPA—from the current case:

Chief Justice Roberts challenged the government’s heavy reliance on Dames & Moore, emphasizing that the Court itself treated that decision as unusually narrow and tied to rare, episodic circumstances. He noted that Dames & Moore addressed a different provision of IEEPA and did not involve tariffs, and he pressed the government to explain why a case the Court portrayed as limited should carry the weight the government was placing on it in support of sweeping tariff authority.

This distinction—”episodic” versus “systematic”—captured something fundamental about the case that transcended particular doctrinal frameworks. Even if the Court accepts some presidential flexibility to respond to specific emergencies in ways that might implicate foreign commerce, does that authority extend to restructuring the entire tariff system on an ongoing basis? Roberts appeared skeptical that it did.

Justice Kagan and the Absence of Limiting Principles

Justice Kagan approached the case through the analytical framework she had applied earlier in FCC v. Consumers Research, where her majority opinion upheld a delegation to the FCC to collect fees “sufficient” to fund universal service programs. In that case, Kagan emphasized that “sufficient” provided both a floor (must collect enough) and a ceiling (can’t collect more than needed), creating a real constraint on agency discretion.

Justice Kagan questioned what substantive limit, if any, constrains the amount of money the government’s reading would allow the President to collect once an emergency is declared. Drawing on the Court’s recent discussion of delegation concerns in Consumers’ Research, she suggested that an exaction with no ceiling—one that could be set at whatever level the decisionmaker prefers—would pose a serious nondelegation problem. She pressed the government to explain how its theory avoids that concern, given the absence of any clear statutory cap or comparable limiting principle on the magnitude of the tariff.

Sauer acknowledged that IEEPA contains no explicit rate cap or proportionality requirement, falling back on the argument that the requirement that actions “deal with” the threat provides adequate constraint. But Kagan appeared unconvinced that this “deal with” language did much work once the threshold for declaring an emergency had been crossed.

This exchange was significant because Kagan had just authored an opinion upholding a delegation of revenue-raising authority. Her skepticism here suggested she saw a difference: the FCC statute contained real limits (”sufficient” meant necessary and no more), while IEEPA appeared to lack comparable constraints on amount.

Justice Kavanaugh: The Potentially Critical Swing Vote Works Through Competing Frameworks

Justice Kavanaugh asked more questions than any other justice, and his line of inquiry revealed genuine intellectual engagement with both sides’ strongest arguments. This pattern—extensive questioning of both sides without a clear lean—often signals a justice working through competing considerations in real time rather than testing arguments he’s already decided against.

Justice Kavanaugh treated the government’s position as a natural candidate for the major questions framework. He emphasized that the government was relying on IEEPA language that had never previously been used—or even argued—to authorize tariffs, even though Congress uses tariff authority expressly in other statutory settings. On the government’s reading, he noted, that same language would support sweeping tariff power across products and countries, in any amount and for any duration, and he pressed why the Court should infer such major authority from statutory text that does not speak in tariff terms.

The government responded that major-questions analysis is a poor fit in this context because the challenged actions operate in a foreign-affairs and national-emergency setting where the President also possesses independent Article II authority—an area where the Court has historically afforded broader discretion.

Separately, Kavanaugh underscored that the Court has often described tariffs on foreign imports as an exercise of the foreign commerce power rather than the taxing power, and he used that framing to probe how the statutory text and historical practice should inform the scope of any tariff authority the President may claim under IEEPA.

The question for Kavanaugh appeared to be: How does he characterize these tariffs? If they’re primarily “domestic” economic regulation—using the taxing power to collect revenue, affecting domestic prices and business decisions—then the major questions doctrine applies and the government loses. If they’re primarily “foreign affairs”—responding to threats from foreign countries using tools of economic statecraft—then his own recent writing suggests courts should presume Congress intended broader presidential flexibility.

At oral argument, Kavanaugh gave no clear signal through questioning alone about which characterization he found more persuasive. His questions to both sides were genuinely probing, suggesting he was still working through the classification problem.

Justice Gorsuch and the Nondelegation Specter

Justice Gorsuch, who has written and spoken about reviving meaningful nondelegation review, used the oral argument to emphasize the constitutional dimensions lurking behind the statutory question.

Justice Gorsuch repeatedly pressed the breadth of the government’s position and the absence of meaningful judicial limits. He challenged the suggestion that the President’s emergency determination is effectively beyond judicial review, describing that approach as an abdication rather than a lawful delegation. He also tested the implications of the government’s interpretation with a concrete hypothetical, asking whether it would permit a President to impose a steep tariff on gas-powered cars and auto parts to address climate change as an “unusual and extraordinary threat from abroad,” and he indicated that such an outcome appeared to follow from the government’s logic. Finally, he drew out the government’s concession that the President lacks inherent tariffing authority in peacetime, framing the dispute as turning on the scope of Congress’s statutory delegation rather than any freestanding Article II power to set tariffs.

Gorsuch’s questions signaled that even if he doesn’t vote to invalidate the tariffs purely on nondelegation grounds—the Court hasn’t struck down a statute as an unconstitutional delegation since 1935—he views the nondelegation concerns as reinforcing the narrow interpretation of IEEPA’s text. His likely approach: join a majority opinion striking down the tariffs on statutory and major questions grounds, then write separately to emphasize the nondelegation concerns and warn Congress about the dangers of open-ended delegations.

Challenges to Curtiss-Wright

The government leaned on the Court’s foreign-affairs cases to argue that traditional nondelegation constraints apply less forcefully in the external context. In defending that position, the Solicitor General invoked Justice Jackson’s Youngstown framework and noted that Youngstown itself discusses Curtiss-Wright, treating its broad language as dicta while using it to support the proposition that delegation limits differ in foreign affairs.

Justice Sotomayor, however, repeatedly redirected the focus to what Congress actually authorized here. She stressed that when Congress intends to permit tariff-like taxing measures, it typically uses tariff or tax terminology, and she emphasized that IEEPA does not use those terms. She also observed that no President had previously used IEEPA to impose tariffs, distinguishing Nixon’s surcharge as arising under a predecessor statute with its own constraints.

Sotomayor’s pointed questioning suggested that at least six justices—the three liberals plus Roberts, Gorsuch, and Barrett—are unlikely to revive Curtiss-Wright‘s most expansive rhetoric about plenary presidential power. The question is whether even the more modest version of foreign affairs deference—the presumption that Congress generally intends to give presidents flexibility in foreign affairs absent specific restrictions—applies to the taxing power.

Justice Barrett and the Remedy Complications

Justice Barrett asked fewer questions than some of her colleagues, but her inquiries focused laser-like on the practical consequences of the Court’s decision

Justice Barrett asked what would happen on the remedial side if the challengers prevailed and whether unwinding the tariffs would be administratively chaotic. Katyal answered that the government had stipulated refunds for the named plaintiffs, and that broader relief would run through the specialized trade-law framework, including the administrative protest procedures set out in 19 U.S.C. § 1514. He acknowledged that the refund process could be difficult and pointed to the Court’s prior cases addressing how courts can manage the disruptive effects of retroactive monetary relief.

These remedy concerns could influence the Court’s ultimate approach in several ways. The Court might strike down the tariffs but explicitly make the ruling prospective only. It might strike down the tariffs and remand to the CIT to fashion appropriate relief. Or it might strike down the tariffs and declare them void ab initio (unlawful from the beginning), leaving companies to navigate the existing administrative process for obtaining refunds.

The Telling Silence: Alito and Thomas

Justice Alito asked relatively few questions to the government, mostly seeking clarification on technical aspects of the statutory scheme and historical practice. His reticence was notable.

Justice Thomas asked little—entirely typical for him, as he rarely speaks during oral arguments. But his past writings and voting record suggest possible sympathy for the government’s position, particularly on matters of executive power in foreign affairs and national security.

Both Alito and Thomas have shown greater willingness than some of their colleagues to defer to executive authority (especially with the current administration) in areas touching on national security. Their relative silence doesn’t necessarily signal agreement with the government—Thomas, in particular, asks few questions regardless of his views—but if the government wins any votes, these two justices represent its best hope for dissents that could form the basis for a future majority if the Court’s composition changes.

What the Questioning Patterns Reveal: Word Count Analysis

One empirical method for assessing judicial leanings is to analyze not just the content of questions but their volume and direction. Justices tend to ask more questions of the side they’re skeptical of—testing arguments, probing for weaknesses, searching for limiting principles. Conversely, they ask fewer questions of the side they’re inclined to support, saving their questions for clarifying points they find persuasive.

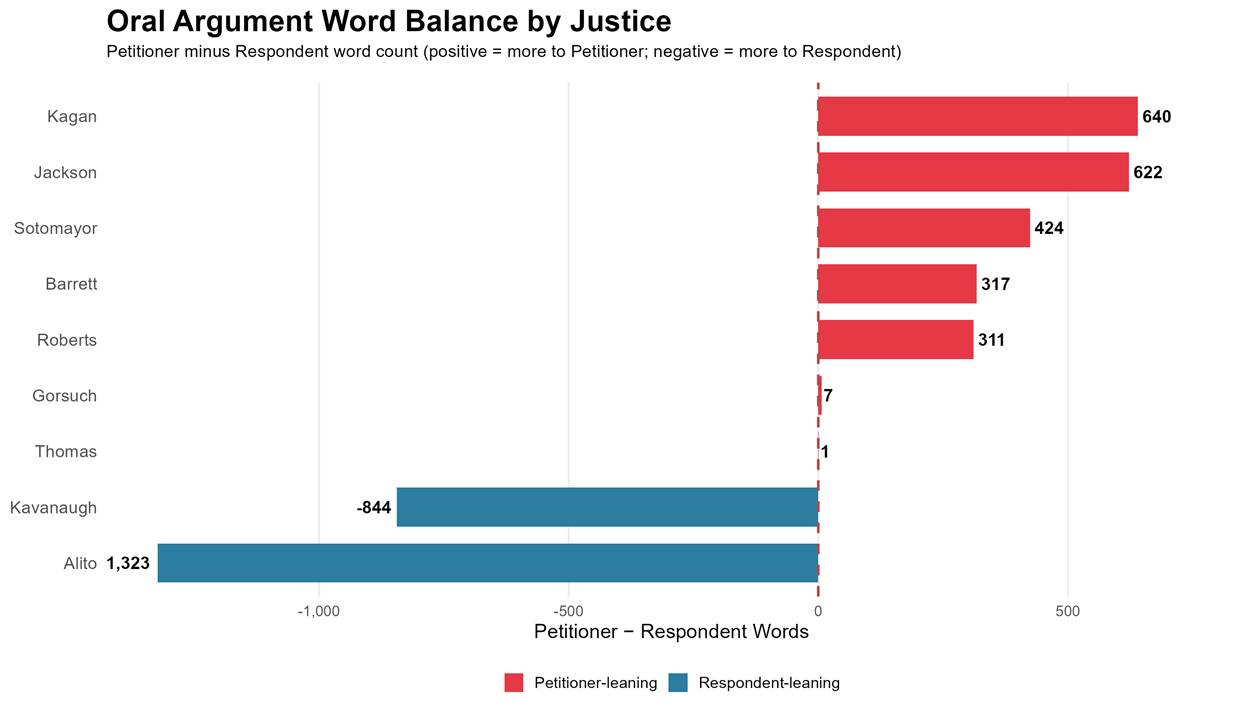

Analysis of the oral argument transcript reveals a striking pattern in the balance of questioning directed at petitioner (the government) versus respondent (the challengers):

Question Word Counts (Petitioner Words Minus Respondent Words):

Justice Alito: -1,323 words (heavily questioned challengers)

Justice Kavanaugh: -844 words (questioned challengers more)

Justice Kagan: +640 words (heavily questioned government)

Justice Jackson: +622 words (questioned government more)

Justice Sotomayor: +424 words (questioned government more)

Justice Barrett: +317 words (questioned government more)

Justice Roberts: +311 words (questioned government more)

Justice Gorsuch: +7 words (essentially balanced)

Justice Thomas: +1 word (asked almost nothing)

Several patterns emerge. Five justices—Kagan, Jackson, Sotomayor, Barrett, and Roberts—directed substantially more questions at the government than at the challengers, suggesting skepticism of the government’s position. This aligns with the qualitative assessment from their questions’ content.

Justice Alito’s pattern points the opposite direction. His extensive questioning of the challengers and relatively few questions for the government suggests he may be the government’s strongest potential vote.

Justice Kavanaugh’s pattern is more ambiguous. He asked more questions of the challengers than the government, but he also asked an enormous number of questions overall—more than any other justice. This could mean genuine uncertainty (testing both sides’ arguments because he’s undecided) or it could mean skepticism of the challengers despite being troubled by aspects of the government’s case.

Most interestingly, Justice Gorsuch asked almost exactly the same number of words to each side. This balance is unusual for Gorsuch, who typically has strong views and asks pointed questions to test the side he opposes. The balanced questioning could mean several things: he’s genuinely torn (unlikely given his strong nondelegation views), he’s already decided but wants to fully develop the record (possible), or he’s asking questions designed to elicit admissions from both sides that he can use in a concurrence (most likely).

Justice Thomas’s minimal participation is entirely typical and reveals nothing about his thinking.

Synthesizing the qualitative content with quantitative patterns, the most likely vote count based on the word and question counts seems to sway 7-2 or 6-3 against the government, with Alito and Thomas as probable dissenters and Kavanaugh as the potential swing vote who could make it 7-2 (if he joins the majority) or 6-3 (if he dissents).

III. THE 91-DAY MYSTERY: WHAT THE TIMING REVEALS ABOUT INTERNAL DELIBERATIONS

At 91 days since oral arguments (as of February 4, 2026), the tariff case occupies a curious position in Supreme Court timing patterns. It has significantly exceeded the historical precedent for expedited cases but remains ahead of the normal pace for divided decisions. Understanding what this timing signals requires examining Supreme Court decision patterns across multiple dimensions: expedited versus normal processing, vote splits, opinion length and complexity, and justice-specific writing speeds.

The Expedited Case Benchmark: A Clear Deviation

When the Supreme Court granted the government’s motion for expedited consideration on September 9, 2025, it sent a clear signal: this case couldn’t wait for normal processing. The Court scheduled oral arguments for November 5—just 57 days after granting certiorari, compared to a typical timeline of 100 to 120 days from cert to argument. The expedited schedule reflected recognition of ongoing harm: daily tariff collections approaching $2 billion, liquidation deadlines passing that could permanently bar refunds, and businesses restructuring supply chains based on tariffs that might be unconstitutional.

Historical data on expedited Supreme Court cases is limited but revealing. The modern Court rarely expedites cases, making each instance significant. When it does accelerate briefing and argument schedules, decisions typically follow within a narrow temporal window:

Recent expedited decisions:

Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson (2021): 39 days from argument to decision (Texas abortion law challenge)

United States v. Trump (2024): 67 days from argument to decision (presidential immunity, decided on final day of term)

These two cases represent different ends of the expedited spectrum. Whole Woman’s Health involved a procedural question about enjoining state court proceedings—doctrinally complex but with a relatively narrow issue for decision. The Court decided quickly with a brief per curiam opinion. United States v. Trump presented fundamental questions about presidential immunity from criminal prosecution, producing a lengthy majority opinion by Chief Justice Roberts with concurrences and dissents. Yet even that weighty case decided in 67 days.

Based on this limited modern precedent, expedited cases appear to decide in a range of approximately 39 to 67 days from oral argument to decision. The tariff case, at 91 days, exceeds even the upper bound of this range by 24 days (36% longer than United States v. Trump) to 52 days (133% longer than Whole Woman’s Health).

This deviation from expedited precedent is notable and requires explanation. When a Court grants expedition, it’s acknowledging urgency that justifies disrupting normal operations—compressing briefing schedules, accelerating oral arguments, and prioritizing deliberation. Yet the deliberation here has stretched well beyond expedited norms.

The Normal Case Comparison: Ahead of Schedule

But context matters. While 91 days is slow for an expedited case, it’s actually fast compared to normal Supreme Court timing for divided decisions derived from the US Supreme Court Database. Comprehensive analysis of Supreme Court decision times from the 2005 through 2024 terms reveals clear patterns:

Baseline timing (argument to decision):

All argued cases: 102 days average

Unanimous decisions (9-0): 90 days average

8-1 decisions: 95 days average

7-2 decisions: 98 days average

6-3 decisions: 113 days average (recent terms: 122 days)

5-4 decisions: 117 days average

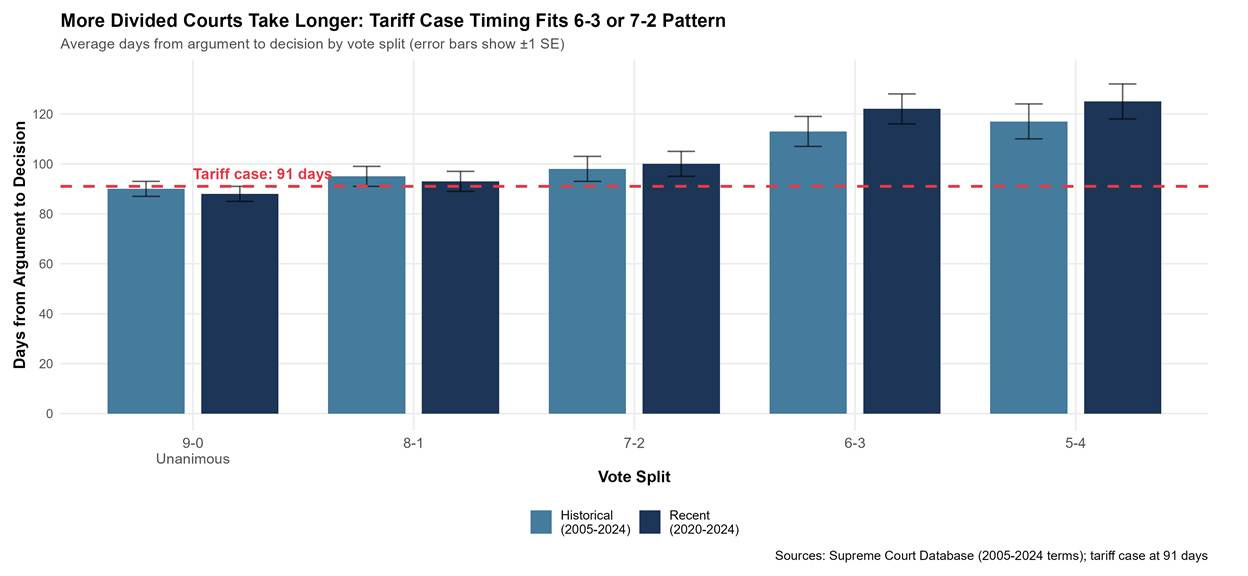

The correlation between vote division and timing is clear: the more divided the Court, the longer decisions take. This reflects both doctrinal disagreement (more time negotiating language) and opinion-writing logistics (more separate opinions to coordinate).

The tariff case, based on oral argument questioning patterns and word count analysis, appears headed for a 6-3 or 7-2 decision. If 6-3, the 113-122 day benchmark means the case at 91 days is actually 22 to 31 days ahead of normal pace. If 7-2, the 98-day benchmark means the case is 7 days behind but still within the normal range of variation.

This seemingly paradoxical situation—slow for expedited, fast for normal—suggests the Court initially expected a more straightforward resolution than materialized. The grant of expedition reflected hope for quick resolution. But as deliberations revealed doctrinal complexity, timing reverted toward normal patterns for divided cases with complex reasoning.

Justice-Specific Writing Speeds: Individual Variation Matters

Not all justices write at the same pace. Analysis of opinion assignments and release dates over the past decade reveals substantial individual variation:

Average time from argument to decision by author (2015-2024 terms):

Fastest: Justice Sotomayor (87.3 days average)

Justice Kagan (91.5 days)

Justice Thomas (93.8 days)

Justice Kavanaugh (97.2 days)

Justice Barrett (99.1 days)

Chief Justice Roberts (102.0 days - median)

Justice Alito (106.4 days)

Justice Jackson (108.7 days)

Slowest: Justice Gorsuch (118.5 days average)

These averages reflect several factors: individual writing styles, complexity of cases assigned, number of separate opinions typically generated, and chambers resources. Justice Sotomayor’s efficiency is notable—she consistently produces opinions more quickly than colleagues, even in complex cases. Justice Gorsuch’s slower pace reflects his detailed, often scholarly writing style and his tendency to generate separate opinions even when joining the majority.

If Chief Justice Roberts writes the majority opinion (most likely given his role and the case’s significance), the 102-day average suggests the case at 91 days remains on schedule. Roberts typically assigns himself major constitutional cases and writes carefully crafted opinions that build coalitions.

If Justice Gorsuch writes a substantial concurrence (likely given his oral argument focus on nondelegation), the 118-day average suggests the case could extend to mid-to-late February or early March while his opinion is finalized.

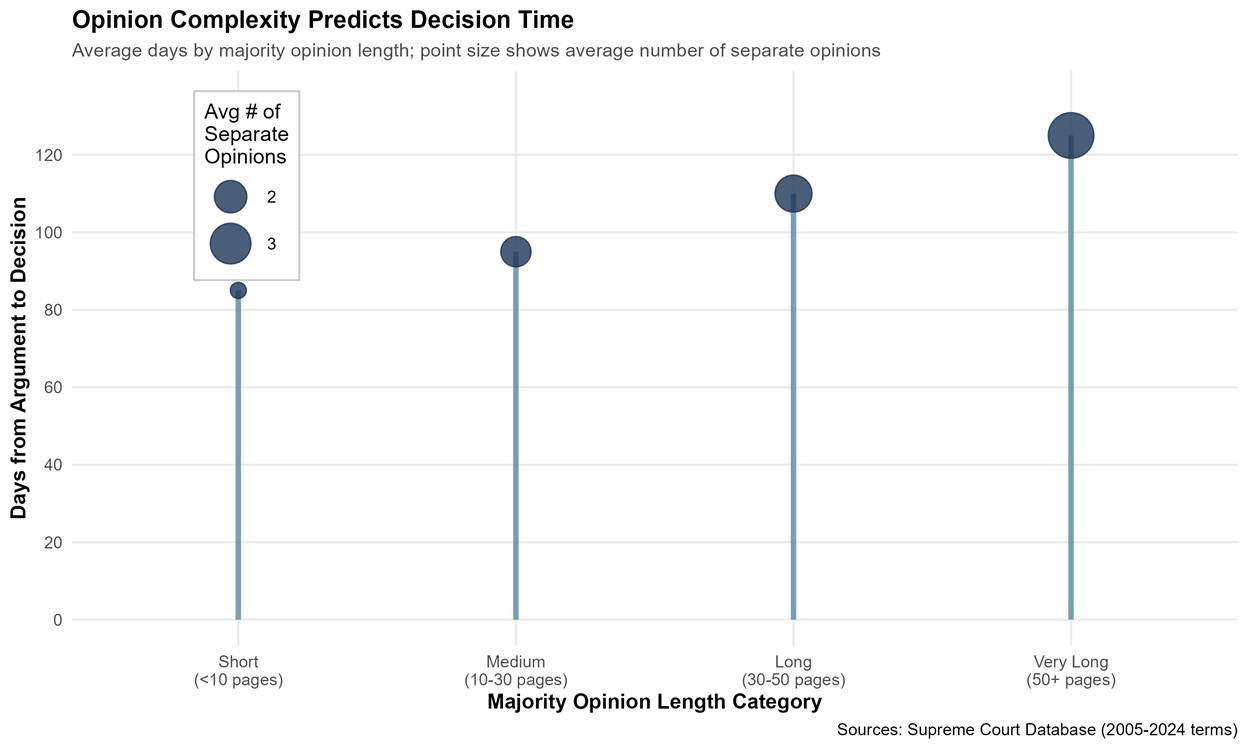

Opinion Length and Complexity: Strong Predictors of Timing

Another strong predictor of decision time is opinion length, which correlates with doctrinal complexity, number of issues addressed, and extent of disagreement requiring careful articulation:

Average timing by majority opinion page length:

Short opinions (under 10 pages): 85 days average

Medium opinions (10-30 pages): 95 days average

Long opinions (30-50 pages): 110 days average

Very long opinions (50+ pages): 125 days average

The tariff case will almost certainly produce a long majority opinion in the 30-50 or even 50+ page range. The doctrinal issues are numerous and complex:

Statutory interpretation of IEEPA’s “regulate... importation” language

Application of major questions doctrine in foreign affairs/national security context (first impression)

Discussion of nondelegation concerns and intelligible principle test

Analysis of “deal with” requirement as limiting principle

Distinguishing Dames & Moore, Yoshida, and other precedents

Addressing remedy questions (prospective vs. retroactive relief)

Responding to dissent’s foreign affairs deference arguments

A thorough treatment of these issues—with proper attention to statutory text, structure, history, and constitutional avoidance concerns—could easily fill 40-60 PDF pages and could very well lead to much lengthier decision in this case. The 110-125 day average for such opinions suggests decisions in late February to early March.

Multiple Separate Opinions: The Complexity Multiplier

Perhaps the strongest predictor of extended timing is the number of separate opinions. When multiple justices write separately—whether concurrences explaining different rationales or dissents defending opposing views—the logistics of opinion circulation, response, and finalization add substantial time:

Average timing by number of separate opinions:

Majority opinion only (no separate writings): 88 days average

One separate opinion: 98 days average

Two separate opinions: 107 days average

Three separate opinions: 116 days average

Four or more separate opinions: 125 days average

The tariff case will likely produce three or four separate opinions:

Majority opinion (likely Roberts): Strikes down tariffs on statutory interpretation and major questions grounds, with careful attention to limiting principles

Gorsuch concurrence: Emphasizes nondelegation concerns, warns Congress about blank-check delegations

Possible Kavanaugh separate writing: If he joins the majority, may write separately to explain the domestic/foreign affairs distinction and when major questions does/doesn’t apply in national security contexts

Alito/Thomas dissent: Argues for foreign affairs deference, distinguishes Dames & Moore differently, reads IEEPA more broadly

Three separate opinions suggest a 116-day timeline (decision around February 25), while four opinions push toward 125 days (decision around March 5).

The Longest Cases: When Deliberations Extend Beyond 150 Days

To calibrate expectations, it’s useful to examine the Court’s longest deliberations over the past two decades. Cases that exceed 150 days from argument to decision share common characteristics:

Supreme Court cases with longest argument-to-decision times (2005-2024):

Gundy v. United States (2018): 261 days

• Nondelegation / administrative power dispute

• 5–3 decision

• The longest argument-to-decision timeline in the set—illustrating that extreme delay can occur even without a razor-thin 5–4 margin.Gill v. Whitford (2017): 258 days

• Partisan gerrymandering challenge

• 9–0 unanimous decision

• A useful counterexample to the “division drives delay” narrative: even a unanimous outcome can land among the very slowest decisions, suggesting that timing can reflect sequencing, assignment, and drafting dynamics rather than ideological fracture alone.Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin (2012): 257 days

• Affirmative action in higher education

• 7–1 decision

• Another lopsided vote that nevertheless took an exceptionally long time—reinforcing that some of the longest timelines reflect complexity and opinion-production dynamics, not just close splits.Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia (2019): 251 days

• Title VII and sexual orientation / gender identity discrimination

• 6–3 decision

• Fits the intuitive pattern that contested alignments can take longer, but it sits alongside unanimous and 7–1 cases—so division is not a sufficient explanation by itself.Allen v. Milligan (2022): 247 days

• Voting Rights Act Section 2 redistricting

• 5–4 decision

• The closest split in the group, consistent with extended deliberation—yet it appears in the same extreme-delay range as cases with wide (and even unanimous) margins.

These cases share several features: (1) mainly divided outcomes involving likely intense internal negotiation; (2) constitutional questions of first impression or precedent-overturning decisions; (3) extensive majority opinions (typically 50+ pages); (4) multiple substantial separate opinions (typically 4-5 total writings); and (5) high political salience requiring careful justification.

The tariff case shares some but not all of these characteristics. It presents questions of first impression (major questions in foreign affairs), will produce multiple opinions (likely 3-4), and involves high stakes. But oral arguments suggested 6-3 or 7-2, not 5-4, implying somewhat less internal division than the cases above. At 91 days, the tariff case remains well short of the 200+ day range of truly extraordinary cases.

Four Theories to Explain the 91-Day Timeline

Theory One: Normal Complexity for This Type of Case

This explanation treats the 91 days as unsurprising given the case’s characteristics: first-impression doctrinal issues, multiple opinion writers, remedy complications, and coalition-building across ideological lines.

The evidence supports this theory. Cases presenting novel applications of major doctrines to new contexts typically require extended deliberation. West Virginia v. EPA (2022), which applied major questions to an environmental agency, took 127 days despite producing only three opinions. Biden v. Nebraska (2023), applying major questions to student loan forgiveness, took 119 days. Both were 6-3 decisions involving Chief Justice Roberts majority opinions.

The tariff case asks the Court to apply major questions doctrine in a context where it has explicitly declined to apply it before: foreign affairs and national security. Justice Kavanaugh’s recent FCC concurrence noted that “the major questions canon has not been applied by this Court in the national security or foreign policy contexts.” Extending the doctrine to this new area—or carefully explaining why these tariffs don’t qualify as “foreign affairs” for purposes of the exception—requires careful reasoning that distinguishes future cases.

Additionally, remedy questions add complexity. Justice Barrett’s oral argument questions about “unwinding” $133 billion suggest the Court may be wrestling with whether to order retroactive relief (refunds through the administrative process) or prospective relief only (tariffs invalid going forward but no refunds). These practical complications can slow deliberations even when the legal merits are clear.

Finally, coalition-building takes time. If Chief Justice Roberts is negotiating to expand a 6-justice core to a 7-2 or even 8-1 supermajority, each additional vote requires accommodating concerns through language adjustments. Roberts has shown himself willing to invest time building broader coalitions on constitutional questions where legitimacy concerns are heightened.

Timeline projection under this theory: Decision by mid-February to early March (100-120 days total). This would align with normal complexity for 6-3 cases with novel doctrine and multiple opinions.

What it means if this theory is correct: The delay signals complexity, not uncertainty about outcome. The core six justices skeptical of the government’s position at oral argument remain opposed, but careful opinion drafting and coalition management explains the extended timeline. Decision may run 6-3 or 7-2 against government with Roberts majority, Gorsuch concurrence on nondelegation, and Alito/Thomas dissent on foreign affairs deference.

Theory Two: Supermajority Building and Institutional Caution

This theory posits that the delay reflects Chief Justice Roberts’s efforts to build the broadest possible coalition—7-2 or even 8-1—for a decision that will significantly constrain presidential power in emergencies.

Roberts has shown particular concern for institutional legitimacy on cases involving the constitutional allocation of authority between branches. His surprising vote to uphold the Affordable Care Act in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), his careful opinion in Trump v. United States (2024) on presidential immunity, and his separate writing in various administrative law cases all reflect sensitivity to how the Court’s decisions affect its institutional position.

Constraining presidential emergency authority—especially in a context where the President has invoked national security and foreign affairs rationales—presents legitimacy concerns. If the Court appears to invalidate emergency actions on a partisan 6-3 vote (with all Republican appointees except the Chief Justice against the government, all Democratic appointees joining), it risks accusations of result-oriented jurisprudence. A 7-2 or 8-1 decision sends a stronger message that legal principles, not politics, drive the outcome.

Achieving supermajority support requires accommodating concerns from justices who might otherwise dissent. Justice Kavanaugh’s foreign affairs worries need addressing—perhaps through careful language explaining that these tariffs are primarily exercises of the domestic taxing power rather than true foreign policy measures. Justice Alito’s historical deference to executive authority in national security might be accommodated through language preserving presidential flexibility in other emergency contexts.

The extra time would be devoted to negotiating opinion language that maintains the core holding (IEEPA doesn’t authorize these tariffs) while adding limiting principles that give potentially dissenting justices comfort about future applications.

Timeline projection under this theory: Decision by late February to early April (110-150 days). The extended timeline reflects ongoing negotiation rather than doctrinal uncertainty.

What it means if this theory is correct: The Court prioritizes legitimacy and coalition-breadth over speed. Decision likely 7-2 or 8-1 against government with very carefully crafted majority opinion that limits presidential tariff authority in this context while preserving flexibility elsewhere. Multiple concurrences may still appear, but justices join the judgment even while expressing different rationales.

Theory Three: Justice Kavanaugh’s Genuine Indecision

This theory treats Justice Kavanaugh as a genuine swing vote who remains undecided about how to characterize the case—domestic economic regulation (where major questions applies) or foreign affairs (where he recently wrote it doesn’t apply).

The evidence for Kavanaugh’s centrality is strong. His extensive questioning at oral argument, his recent FCC concurrence creating a explicit domestic/foreign affairs framework, and his historical pattern of writing separately to explain doctrinal nuances all suggest he’s working through first-order classification questions.

If Kavanaugh is genuinely torn, the delay could reflect both sides attempting to win his vote through draft opinions. The majority might be circulating drafts emphasizing that tariff collection is inherently domestic (taxing Americans, affecting U.S. prices, raising revenue for the federal Treasury). The dissent might be circulating drafts emphasizing foreign affairs dimensions (responding to threats from foreign countries, using economic tools of statecraft).

Kavanaugh’s vote matters not just for the count (turning 7-2 into 6-3) but for the reasoning. If he joins the majority, he’ll likely write separately to explain when major questions does and doesn’t apply in cases with foreign affairs elements. If he dissents, his rationale could provide the foundation for future challenges to expand presidential authority.

This theory is less likely than Theories One or Two for several reasons. First, Kavanaugh’s questioning, while extensive, seemed more probing than genuinely uncertain—he appeared to be testing arguments rather than searching for answers. Second, his recent FCC concurrence strongly suggests he’s already thought through the major questions/foreign affairs/nondelegation intersection, making it unlikely he’s starting from scratch. Third, a single wavering justice typically doesn’t delay decisions by 30+ days beyond expedited precedent—the Court can decide while accommodating a separate writing.

Timeline projection under this theory: Unpredictable—could drop any day if Kavanaugh decides quickly, or extend to 130+ days if he genuinely remains torn.

What it means if this theory is correct: Significant uncertainty remains about the outcome. If Kavanaugh joins the majority (most likely), decision is 7-2 against government with his concurrence explaining the domestic/foreign line. If he joins the dissent, decision is 6-3 against government. If he somehow persuades one more justice (Roberts or Barrett) to join a dissent on foreign affairs grounds, decision could be 5-4 for government—a upset that would dramatically expand presidential emergency authority.

Theory Four: Remedy Paralysis

This theory posits that while the Court agrees the tariffs are unlawful, justices disagree about remedy—whether to order full retroactive relief (refunds through administrative process) or limit relief to prospective application only.

Justice Barrett’s oral argument questions focused extensively on remedy mechanics: what happens to collected money, how companies obtain refunds, why some companies are barred even if the Court rules in their favor. These concerns suggest potential disagreement about appropriate relief even if the merits are clear.

The remedy debate involves competing principles. On one hand, basic fairness suggests that if tariffs were unconstitutional, companies shouldn’t have to bear the cost. On the other hand, retroactive relief creates administrative chaos: billions in refunds processed case-by-case through the Court of International Trade over 2-3 years, with companies that missed technical deadlines permanently barred despite constitutional violations.

If different justices prefer different remedies, achieving a majority might require extensive negotiation. Some might prefer full retroactive relief (traditional approach to unconstitutional taxes). Others might prefer prospective only (avoids administrative burden). Still others might want to remand to the CIT without specifying remedy (let specialized court handle details).

Historical precedents support this concern. Northern Pipeline Construction Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co. (1982), which struck down the bankruptcy court system, may have been slowed partly due to disagreement about appropriate remedy and implementation timeline. Similarly, United States v. Booker (2005), which invalidated mandatory sentencing guidelines, spent time crafting a remedial scheme.

However, this theory seems least likely for the tariff case. The Court could easily strike down the tariffs and remand to the CIT for administration of relief, avoiding the need to resolve remedy details itself. Moreover, remedy disagreements typically produce fractured judgments with multiple opinions offering competing approaches. The oral argument questioning patterns suggest broader agreement on the merits than remedy paralysis would imply.

Timeline projection under this theory: Late March to June (130-200 days), approaching or exceeding the longest cases of the past two decades.

What it means if this theory is correct: Fragmented judgment with no clear majority opinion, multiple concurrences and dissents offering different remedy frameworks, remand to CIT with limited guidance. Would signal significant internal division beyond the 6-3 oral argument impression suggested.

What 91 Days Actually Signals: Synthesizing the Evidence

Weighing all evidence, the most likely explanation for the 91-day timeline reflects:

Doctrinal novelty: First application of major questions to foreign affairs context requires careful reasoning

Multiple opinions: Three or four separate writings (majority, Gorsuch concurrence, possible Kavanaugh separate, Alito/Thomas dissent) add coordination time

Remedy complexity: Barrett’s concerns require majority opinion to address refund mechanics even if remanding details to CIT

Coalition negotiation: Roberts likely seeking Kavanaugh’s vote to make it 7-2, requiring accommodation of foreign affairs concerns through careful framing

What the timing does not necessarily signal:

Government victory: Cases where government unexpectedly wins tend to decide faster to affirm executive action and end uncertainty. Extended deliberation typically means complexity in crafting the opinion against government.

Deadlock or 5-4 division: The 91-day timeline fits normal patterns for 6-3 or 7-2 decisions with complex doctrine and multiple opinions. True deadlock or 5-4 votes produce much longer timelines (150-200+ days) or highly fractured judgments.

Kavanaugh as true swing: His extensive questioning and recent writings suggest he’s testing arguments and working through application, not fundamentally undecided. Most likely outcome remains that he joins majority, possibly writing separately.

The timeline is most consistent with a mid-February to early March decision (100-120 days total), likely 6-3 or 7-2 against government, with Chief Justice Roberts majority opinion applying major questions doctrine, Justice Gorsuch concurrence emphasizing nondelegation, and Justice Alito/Thomas dissent arguing for foreign affairs deference.

The USTR Greer Statement: Confidence or Spin?

On February 3, 2026 (88 days post-argument), U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer told CNBC:

“The Supreme Court is taking its time to rule on a case challenging the legality of President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs given the ‘enormous’ stakes involved... Large revenues had been collected under the tariffs and the plaintiffs did not have ‘an open and shut case.’... We’ve built a new trade order on the back of these tariffs... So the stakes are enormous, and I think the court is being very careful and considerate as to how they deal with this issue of extreme national interest.”

Greer’s comments admit two interpretations:

Interpretation One—Genuine Government Confidence: The government’s internal assessment is that Court deliberations have gone better for them than oral arguments suggested. Perhaps Justice Kavanaugh has signaled he’s persuaded by the foreign affairs framing, or Chief Justice Roberts has expressed concerns about disrupting the “new trade order” that businesses have adapted to. The delay reflects ongoing negotiation toward a government-favorable outcome (5-4 or 6-3 upholding tariffs).

Interpretation Two—Preemptive Spin: The government knows it’s going to lose based on oral arguments and the extended deliberation time (which fits normal opposition-drafting patterns). Greer’s comments prepare the public for defeat by framing it as a “close case” where the government had “strong arguments” and the Court had to be “careful and considerate” given “enormous stakes.” This narrative-shaping makes the loss less politically damaging.

The timing evidence favors Interpretation Two (spin). If the government were winning—an outcome few observers expected after oral arguments—the decision would likely come faster. When the Court upholds executive power, it typically acts quickly to affirm the action and end uncertainty. Extended deliberation is more consistent with a Court carefully crafting an opinion constraining executive authority—requiring time to develop limiting principles, respond to dissent arguments, and build coalition support.

Moreover, Greer’s specific framing—”not an open and shut case,” “enormous stakes,” “careful and considerate”—sounds like language designed to soften a loss. By emphasizing the complexity and stakes, the government can portray the defeat as reflecting difficult legal questions rather than clear executive overreach.

That said, the extended timeline beyond expedited precedent does suggest the case is more complex than initially anticipated. It’s possible Greer’s confidence reflects genuine uncertainty within the Court, even if the most likely outcome remains a decision against the government.

IV. THE REFUND NIGHTMARE: EVEN VICTORY DOESN’T GUARANTEE MONEY BACK

While the Supreme Court deliberates, hundreds of companies face an urgent, unforgiving deadline system that could permanently bar them from refunds even if the Court rules in their favor. This administrative reality—rooted in customs law’s liquidation process—has triggered an explosion of protective litigation in the Court of International Trade that will continue for years regardless of how the Supreme Court rules.

The Liquidation Trap: How Companies Lose Refund Rights Forever

The customs liquidation system creates a cruel paradox: companies must preserve their rights through technical compliance with deadlines while awaiting judicial resolution of the underlying legal question. Miss a deadline—even by one day—and you’re barred from relief regardless of the merits.

The liquidation process works as follows:

Entry and Payment: When goods arrive, the importer pays estimated duties to Customs and Border Protection based on the declared value and applicable tariff rates.

Administrative Review: CBP reviews the entry declaration, which can take months. During this period, the duty amount remains provisional.

Liquidation: Approximately 314 days after entry (the statutory maximum is one year), CBP “liquidates” the entry—makes a final determination of duties owed. Once liquidated, the duty assessment becomes final as a matter of law unless timely protested.

Protest Window: Importers have 180 days from the date of liquidation to file a protest with CBP challenging the duty assessment.

Litigation Window: If CBP denies the protest (or fails to act within prescribed timeframes), importers have another 180 days to file suit in the Court of International Trade.

Permanent Bar: Miss any deadline and you’re permanently barred from obtaining a refund, even if a court later holds the underlying tariff unconstitutional.

Potentially problematic, not all liquidations are protestable. In Rimco Inc. v. United States (2024), the Federal Circuit held that where CBP acts in a “ministerial capacity”—mechanically applying a tariff rate without exercising discretion—the liquidation cannot be challenged through the protest process. For IEEPA tariffs, which apply automatically to all covered imports, many liquidations may fall into this non-protestable category.

The Timeline of Crisis: Liquidations Passing During Supreme Court Deliberation

The timing creates urgency. Companies began importing under IEEPA tariffs in April 2025. With liquidation occurring approximately 314 days after entry, the first liquidation deadlines began arriving in December 2025—while the Supreme Court case remained pending.

For companies facing December liquidations, the calculus was stark:

Option A: File protective protest and lawsuit to preserve rights, incurring legal costs with uncertain prospects

Option B: Wait for Supreme Court decision, risking permanent loss of refund rights if liquidation occurs before decision

Most sophisticated importers chose Option A, flooding the Court of International Trade with protective suits beginning immediately after oral arguments. The timing is revealing: the first wave of suits filed on November 11, 2025—just six days after Supreme Court oral arguments—suggests companies were waiting to assess the justices’ reception before committing to expensive litigation.

The AGS Consolidation: A Cross-Section of American Commerce

The lead case in the Court of International Trade, AGS Company Automotive Solutions v. United States (Case No. 1:25-cv-00255), quickly became a consolidation of over 108 companies by late December 2025. The roster reads like a cross-section of the American economy:

Notable plaintiffs (partial list):

Costco Wholesale Corp. (filed Nov. 28, 2025, facing Dec. 15 liquidation deadline)

Toyota Tsusho America, Inc.

Yokohama Tire Corporation

Kawasaki Motors Corp., U.S.A.

Bumble Bee Foods, LLC

Revlon Consumer Products Corporation

Ferguson Enterprises, LLC

Alcoa USA Corp.

Mazak Corporation

Ricoh USA, Inc.

Valeo North America, Inc.

Dana Automotive Systems Group, LLC

Schnitzer Steel Industries, Inc.

Interstate Batteries, Inc.

EssilorLuxottica of America Inc.

ViewSonic Corporation

Moog Inc.

The list spans Fortune 500 corporations (Costco, Toyota, Alcoa) to mid-sized manufacturers to small businesses. Industries include automotive, retail, food and consumer goods, industrial equipment, electronics, and raw materials. Geographic distribution is nationwide.

The litigation timeline:

November 11, 2025: First six cases filed (six days after SCOTUS oral argument)

November 20: First consolidation order (24 cases)

November 28: Costco files suit (December 15 liquidation deadline approaching)

December 3: Second consolidation order (21 additional cases, includes Costco)

December 8: Third consolidation order (8 additional cases)

December 22: Fourth consolidation motion (55 additional cases)

Total by late December: 108+ cases consolidated in AGS lead case

But the AGS consolidation represents only a fraction of total filings. Case numbers in the CIT docket reached into the 900s by late December, suggesting 600+ individual cases filed.

Government’s Response: Refusing Extensions, Then Stipulating to Refund Authority

The government’s approach evolved over the course of the litigation in ways that reveal expectations about the Supreme Court outcome.

Initially, CBP took a hard line. On October 16, 2025, CBP sent letters to companies requesting extensions of liquidation deadlines, denying all extension requests. The message was clear: liquidations would proceed on schedule regardless of the pending Supreme Court case. Companies would need to file protective suits if they wanted to preserve rights.

When companies filed a consolidated motion for preliminary injunction asking the CIT to suspend all liquidations pending the Supreme Court’s decision, the government opposed. On December 11, 2025, DOJ argued that companies had adequate remedies through the protest process and that suspending liquidations would disrupt CBP’s normal operations.

On December 15, 2025, the CIT denied the preliminary injunction (Slip Op. 25-154). The court’s reasoning: companies can protect their rights through timely protests and suits; a blanket suspension of liquidations would be an extraordinary remedy not justified by the circumstances. The court essentially forced companies to litigate defensively while awaiting Supreme Court resolution.

But eight days later, on December 23, 2025, the CIT sua sponte stayed all IEEPA tariff cases pending the Supreme Court’s “final, unappealable decision.” The stay order noted the mounting volume of cases and stated the court would “determine the appropriate next steps for resolution of the new IEEPA tariff cases” after the Supreme Court ruled.

Critically, the stay did not prevent liquidations from occurring. It merely froze the judicial proceedings. Companies still needed their protective suits on file; the stay just prevented those cases from moving forward until the Supreme Court provided guidance.

The most significant development came on January 14, 2026. The government stipulated that it “do[es] not intend to challenge the [c]ourt’s authority to order reliquidation” in any IEEPA tariff case “challeng[ing] IEEPA tariffs in a manner and on grounds that substantially overlap with” the Supreme Court case. Importantly, the government’s motion stated this stipulation “should apply to all current and future similarly situated plaintiffs.”

This stipulation is telling. The government is conceding the mechanism for refunds if it loses at the Supreme Court: the CIT has authority to order CBP to reliquidate entries and issue refunds. But the stipulation doesn’t concede liability—the government isn’t agreeing the tariffs are unlawful, just agreeing not to fight about the refund process if the Supreme Court rules against them.

The stipulation suggests the government is preparing for a Supreme Court loss and wants to streamline the post-decision administrative process rather than fighting trench warfare over refund mechanics in hundreds of individual cases.

If the Government Loses: The Multi-Year Refund Process

Assuming the Supreme Court strikes down the IEEPA tariffs, here’s what might happen next:

Phase 1: CIT Lifts Stay (Days 1-14 after SCOTUS decision) The Court of International Trade may immediately lift the stay on all consolidated IEEPA tariff cases. Companies that filed protective suits can now proceed with their claims.

Phase 2: Test Cases (Months 1-6) The CIT will likely select 5-10 “test cases” representing different industries, tariff categories, and fact patterns. The AGS lead case will almost certainly be one. These test cases will proceed to briefing and decision first, establishing precedent for the hundreds of other consolidated cases.

Given the government’s January 14 stipulation, these test cases may proceed on abbreviated briefing. The core legal question—whether IEEPA authorized the tariffs—has been answered by the Supreme Court. The remaining issues are primarily administrative: which entries are covered, what amounts are due, what interest rate applies.

Phase 3: Test Case Decisions (Months 4-9) The CIT will issue decisions in the test cases ordering CBP to reliquidate the affected entries and issue refunds. These decisions will establish the template for resolving the remaining cases.

Phase 4: Application to Remaining Cases (Months 6-18) The CIT will apply the test case precedent to the remaining consolidated cases, issuing orders on a rolling basis. Given the volume (600+ cases, potentially thousands more), this will be a prolonged administrative process even with streamlined procedures.

Phase 5: CBP Processes Refunds (Months 12-36) For each case where the CIT orders reliquidation (if any), CBP must administratively process the refund. This involves:

Identifying all entries covered by the order

Recalculating duties owed (removing IEEPA tariffs)

Calculating interest from date of payment to date of refund

Processing payment through Treasury

Who Gets Refunds and Who Doesn’t

Even if the Supreme Court strikes down the tariffs, not everyone gets their money back:

Companies that will most likely receive refunds:

Companies that filed protective suits in CIT (108+ in AGS consolidation, 600+ total)

Companies that filed timely protests with CBP (within 180 days of liquidation)

Companies whose entries haven’t yet liquidated (can file protests when liquidation occurs)

Companies that will not likely receive refunds:

Companies that missed protest deadlines (180 days from liquidation)

Companies that missed litigation deadlines (180 days from CBP denial of protest)

Companies whose liquidations are deemed “ministerial” and non-protestable under Rimco

Downstream parties (retailers who paid higher wholesale prices, consumers who paid higher retail prices)

Even though the tariffs may be declared unconstitutional, companies that failed to navigate the technical requirements of customs law lose their money forever. There’s no equitable exception for constitutional violations. As Justice Barrett noted at oral argument, this seems fundamentally unfair—but it’s what current law provides.

Estimated refund amounts:

Total IEEPA tariff collections through mid-December 2025: $133+ billion

Companies with preserved refund rights: Likely 60-70% of total (rough estimate based on filing patterns)

Potential refund exposure: $80-90 billion

The Section 301 Precedent: Still Litigating After Seven Years

Companies hoping for quick refunds should temper expectations based on historical precedent. The In re Section 301 Cases litigation in the Court of International Trade, challenging Trump’s 2018-2019 China tariffs under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, provides a sobering example.

That litigation began in 2019. As of 2026, it remains ongoing—more than seven years later. The CIT has issued some decisions favorable to plaintiffs on legal theories, but the administrative process of identifying covered entries, calculating refunds, and processing payments continues to grind forward.

If the Section 301 precedent holds, companies in the IEEPA litigation should expect:

Years of administrative proceedings in CIT

Battles over scope of relief (which entries covered, which tariff categories)

Disputes over interest calculations and payment timing

Potential government appeals on discrete issues even if main holding is clear

The Section 301 cases involve somewhat different legal theories (whether USTR exceeded Section 301 authority, whether procedural requirements were satisfied). But the administrative challenges are similar: thousands of entries, millions of individual transactions, case-by-case determination of refund amounts.

If the Government Wins: No Refunds, Ever

If the Supreme Court upholds the IEEPA tariffs (unlikely based on oral arguments but possible), the consequences for companies are stark:

All 600+ protective suits in CIT will be dismissed

Companies are permanently barred from obtaining refunds

The $133+ billion collected stays with the government

Presidential authority to impose emergency tariffs is massively expanded

Future limitations must come from Congress (unlikely in divided government)

Companies would have no further legal recourse. The Supreme Court’s decision would be final. The “new trade order” that USTR Greer referenced would become permanent—or at least would remain until Congress amended IEEPA to explicitly prohibit tariffs (politically unlikely).

The only potential upside for companies is that they could at least cease spending money on protective litigation. The legal uncertainty would be resolved, allowing businesses to plan with certainty (even if that certainty is unfavorable).

V. THE DOCTRINAL SYNTHESIS: THREE FRAMEWORKS IN COLLISION

The oral arguments and subsequent deliberation reflect the collision of three distinct doctrinal frameworks, each with different implications for the scope of presidential power:

Framework One: Major Questions Doctrine (Challengers’ Primary Theory)

Under this framework, applied most clearly in West Virginia v. EPA (2022) and Biden v. Nebraska (2023), courts presume Congress doesn’t delegate decisions of “vast economic and political significance” through vague or ancillary statutory provisions. Clear congressional authorization is required.

Application to tariffs:

$133 billion in collections = vast economic significance by any measure

Affecting hundreds of billions in annual trade = vast political significance

IEEPA’s “regulate... importation” language never mentions “tariffs,” “duties,” or “rates”

Congress explicitly authorized tariffs in other statutes (Section 232, 301) using precise language

Textual silence in IEEPA + major economic impact = no clear authorization

The foreign affairs complication: Justice Kavanaugh’s recent FCC concurrence stated major questions “has not been applied” in national security/foreign policy contexts because “Congress intends to give the President substantial authority and flexibility.” This creates the central classification question: are these tariffs “domestic” (economic regulation, taxing) or “foreign affairs” (responding to foreign threats)?

Why challengers likely win on this framework: Even if some foreign affairs elements exist, the core function of tariffs is domestic—raising revenue from Americans, affecting U.S. prices and business decisions, exercising the taxing power. Six justices appeared to accept this characterization at oral argument.

Framework Two: Nondelegation Doctrine (Gorsuch’s Emphasis)

Under the intelligible principle test from J.W. Hampton, Jr., & Co. v. United States (1928), Congress must provide standards to guide and constrain executive discretion. The executive can “fill in the details” of legislative policy, but Congress must make the fundamental policy choices, especially on “important subjects.”

Application to tariffs:

Taxing power is quintessentially legislative (Article I, Section 8)

Framers gave taxing power to Congress precisely to prevent executive taxation without consent

If IEEPA allows unlimited tariffs at presidential discretion, only constraint is that President declares emergency (which President determines)

This gives executive a “blank check” to exercise legislative power

Raises grave constitutional concerns even if not outright unconstitutional

Why the Court will likely avoid pure nondelegation holding: The Court hasn’t struck down a statute solely on nondelegation grounds in quite some time. Justices remain divided on whether to reinvigorate the doctrine. But nondelegation concerns reinforce the narrow reading of IEEPA under Framework One.

If this is the emphasis, Gorsuch will possibly join a majority opinion based on statutory interpretation and major questions and write separate concurrence emphasizing nondelegation concerns and warning Congress about open-ended delegations.

Framework Three: Foreign Affairs Deference (Government’s Best Hope)

Under this framework, drawing on United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936) and Dames & Moore v. Regan (1981), courts traditionally defer to presidential action in foreign affairs, especially during emergencies involving foreign countries.

Government’s argument:

Drug trafficking from Mexico/China = foreign threat requiring foreign affairs response

IEEPA is foreign affairs statute (in Title 50, “War and National Defense”)

President has constitutional authority to conduct foreign relations

Tariffs are traditional tool of economic statecraft and diplomatic leverage

Courts should defer to presidential judgment about appropriate response to foreign threats

Why this framework likely loses:

Sotomayor directly challenged Curtiss-Wright as “discredited“ - modern doctrine (Youngstown) requires congressional authorization even in foreign affairs