The First Two Weeks: What Supreme Court Oral Arguments Reveal About the Term Ahead

The first oral argument sitting of the Term is under the justices' belts but what does it show about the justices' interactions and what does it mean for the decisions down the line?

How the Court Reasons in Real Time

The Court’s early arguments reveal a procedural term—thresholds first, sometimes remedies before merits, and rules trial judges can apply.

The Supreme Court’s opening two weeks of oral arguments this October offered something the shadow docket never can: a window into how the justices think through hard cases in real time. While emergency orders arrive with sparse reasoning and no public debate, these early arguments—covering everything from overnight recesses in criminal trials to the arcana of postal-service liability—revealed a Court preoccupied less with sweeping doctrine than with the mechanics of decision-making itself. Who may sue? What can a court actually order? How will a rule work when a trial judge tries to apply it at midnight?

The pattern that emerges from transcripts and questioning data is striking. Across these first sittings, the justices returned again and again to thresholds, remedies, and administrability—the architectural questions that determine whether a case gets decided at all, and if so, how narrowly. That focus tells us something important about the term ahead. This is a Court preparing to decide cases on procedural grounds where it can, testing the practical consequences of any ruling before committing to it, and showing more interest in workable lines than in broad pronouncements.

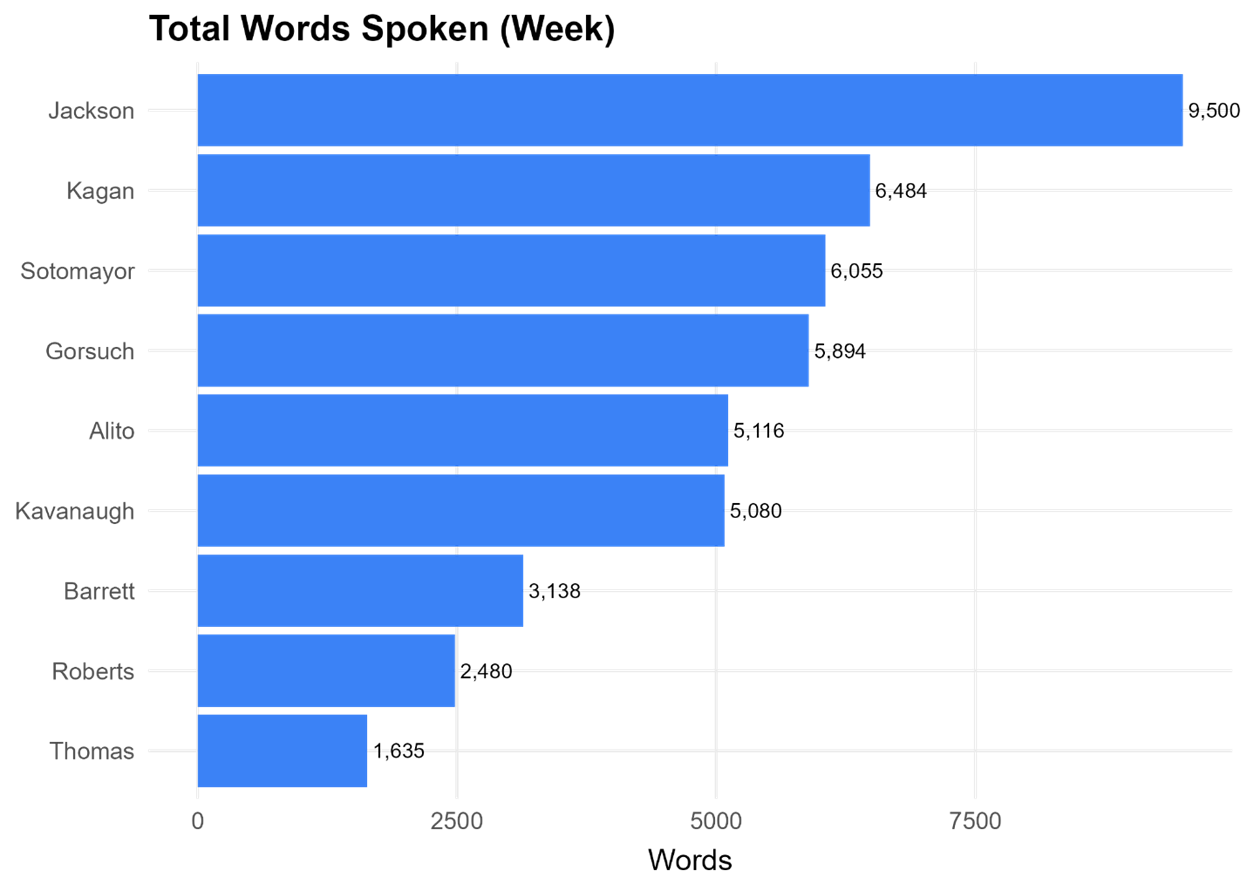

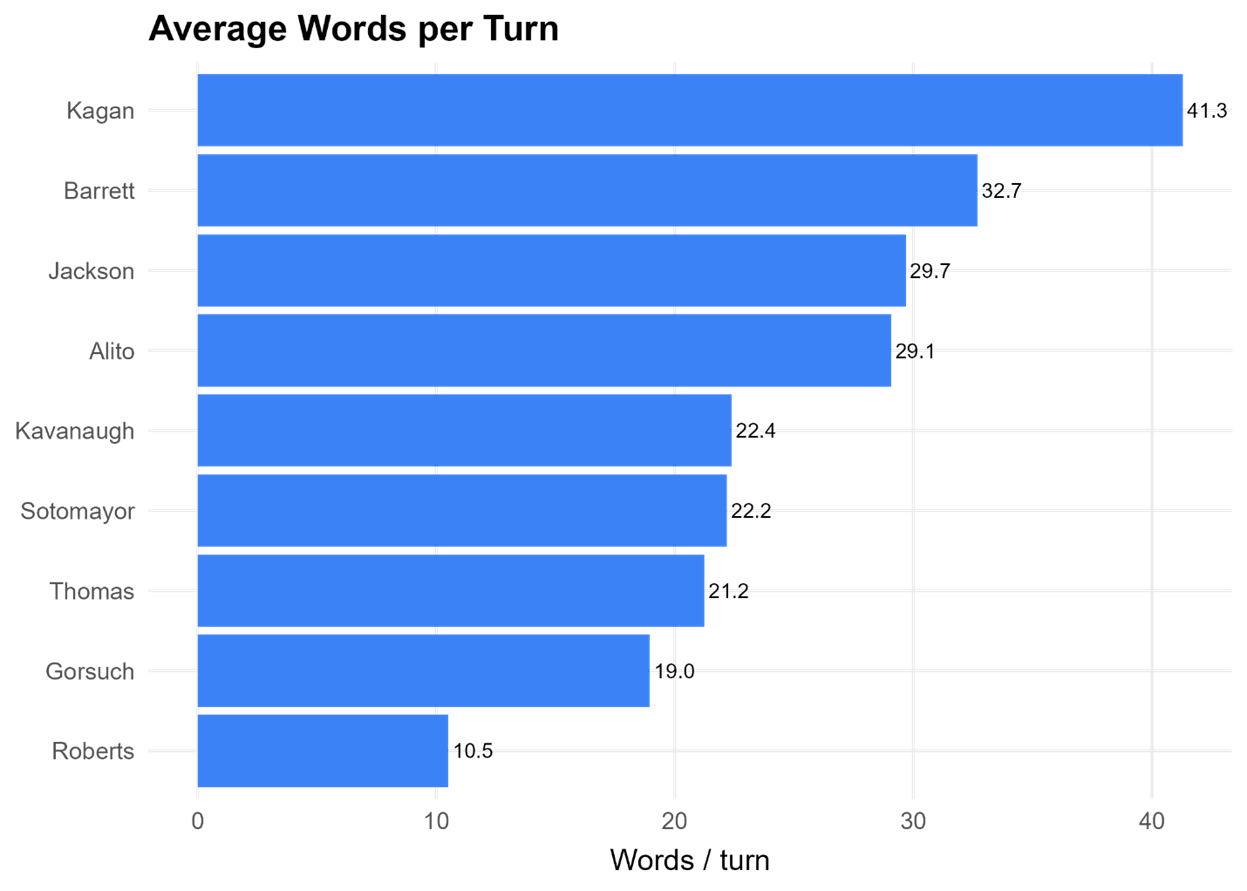

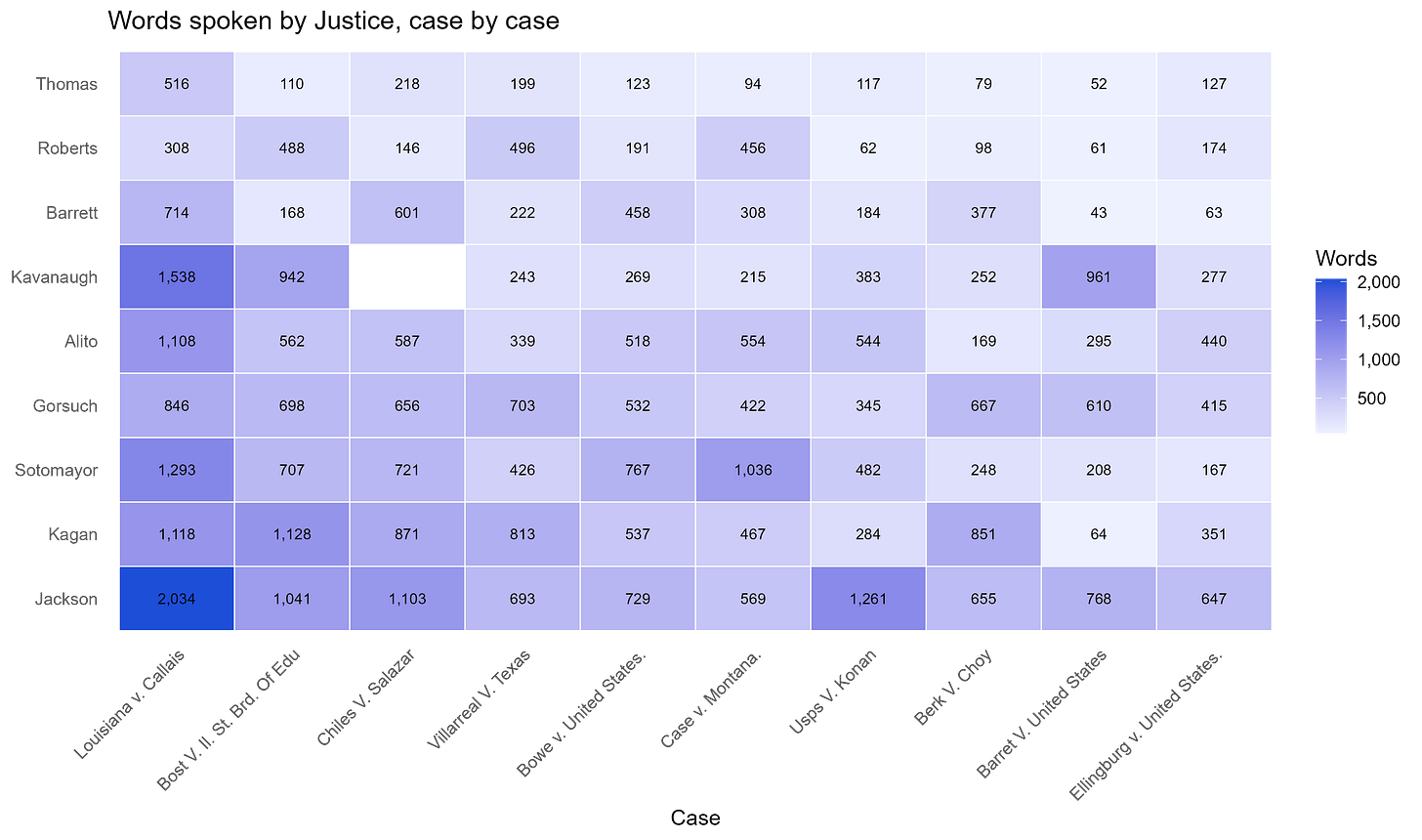

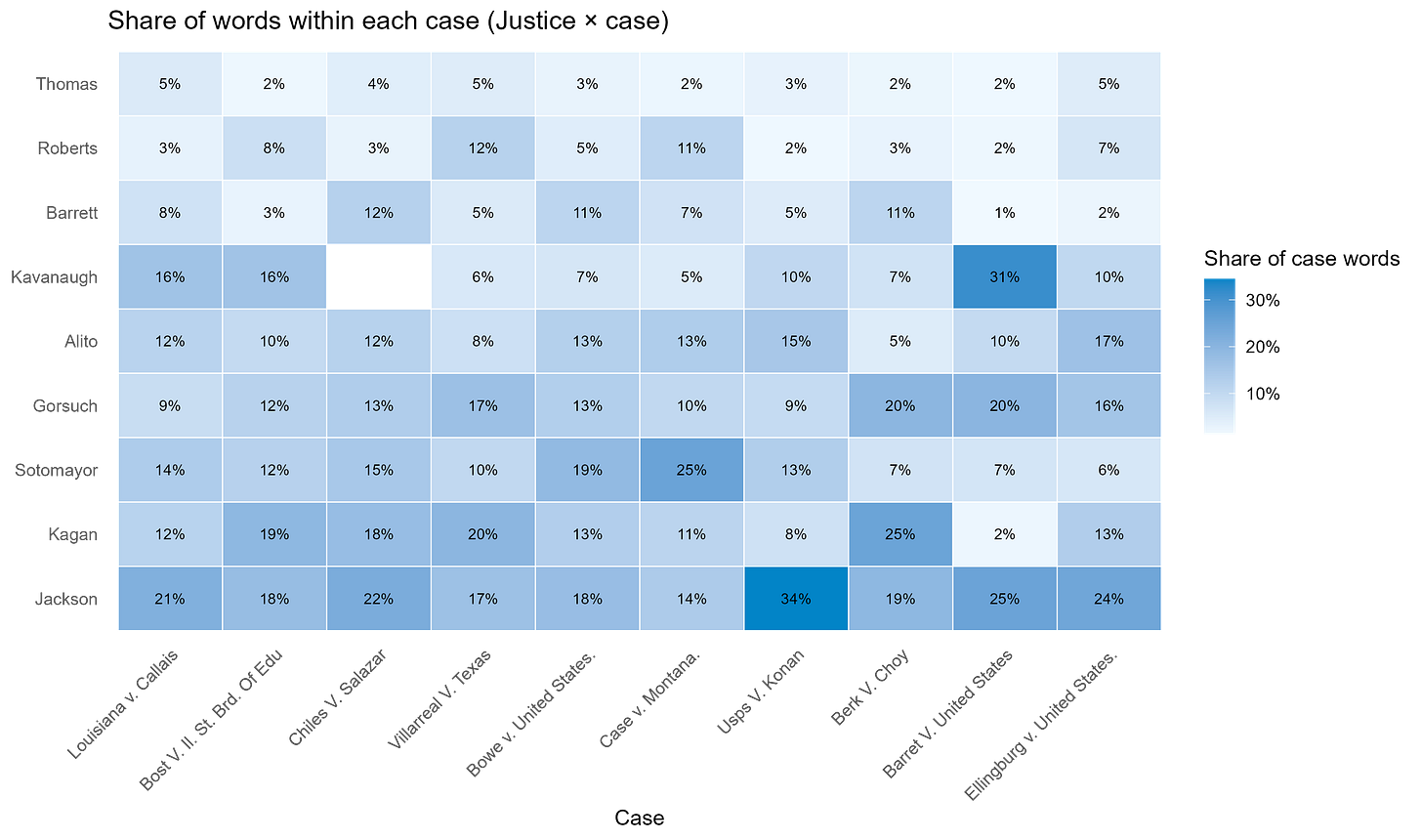

The numbers underline the pattern. Justice Jackson led the Court in total words spoken, with Justice Kagan close behind and Justice Sotomayor in third. Justices Gorsuch, Alito, and Kavanaugh formed a middle tier, while Justice Barrett spoke somewhat less and the Chief Justice and Justice Thomas least. But volume alone doesn’t capture the story. Average turn length—a measure of how much a justice says before yielding the floor—shows Justice Kagan taking the longest interventions, followed by Justice Barrett and Justice Jackson. These justices tend to use extended questions to frame alternatives and press counsel on competing readings. The Chief Justice kept the shortest turns, a managerial style aimed at narrowing issues and moving things along; Justices Gorsuch and Thomas were similarly concise.

What the justices chose to ask about matters as much as how much they spoke. And what stands out across these two weeks is how often standing and remedy questions arrived before any sustained discussion of the merits.

Standing, Remedies, and the Order of Operations

In several arguments, the Court put thresholds and remedies ahead of the merits—often deciding the path before the doctrine.

In Bost and the Chiles, the opening minutes tested injury, traceability, and redressability. The Court made threshold questions the point of the exchange, not a passing formality. Consider a single line from the Illinois dispute, where Justice Kavanaugh cut straight to consequences: “What’s the remedy—do you throw out those votes?” In Chiles, the bench pressed whether a state’s disavowal of enforcement gave the challengers anything concrete to sue over: “They’ve disavowed it. How does that give you standing?”

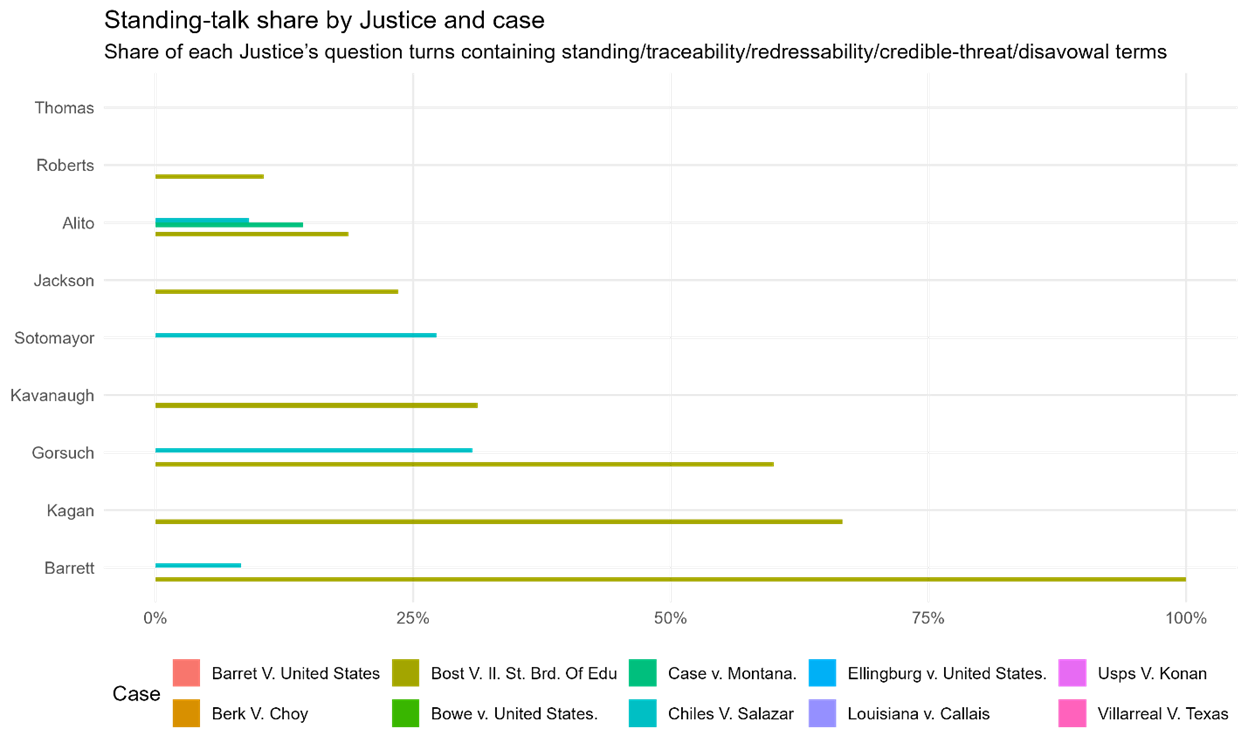

One way to see this pattern is to track when standing vocabulary appears in each justice’s questions—terms like injury, traceable, redressability, credible threat. The data show that in several arguments, standing language dominated early questioning, particularly from Justices Jackson, Kagan, and Kavanaugh. This isn’t lawyers clearing their throats before the real argument begins. It’s the Court signaling that the path to any decision will be shaped by what relief is lawful and workable to grant.

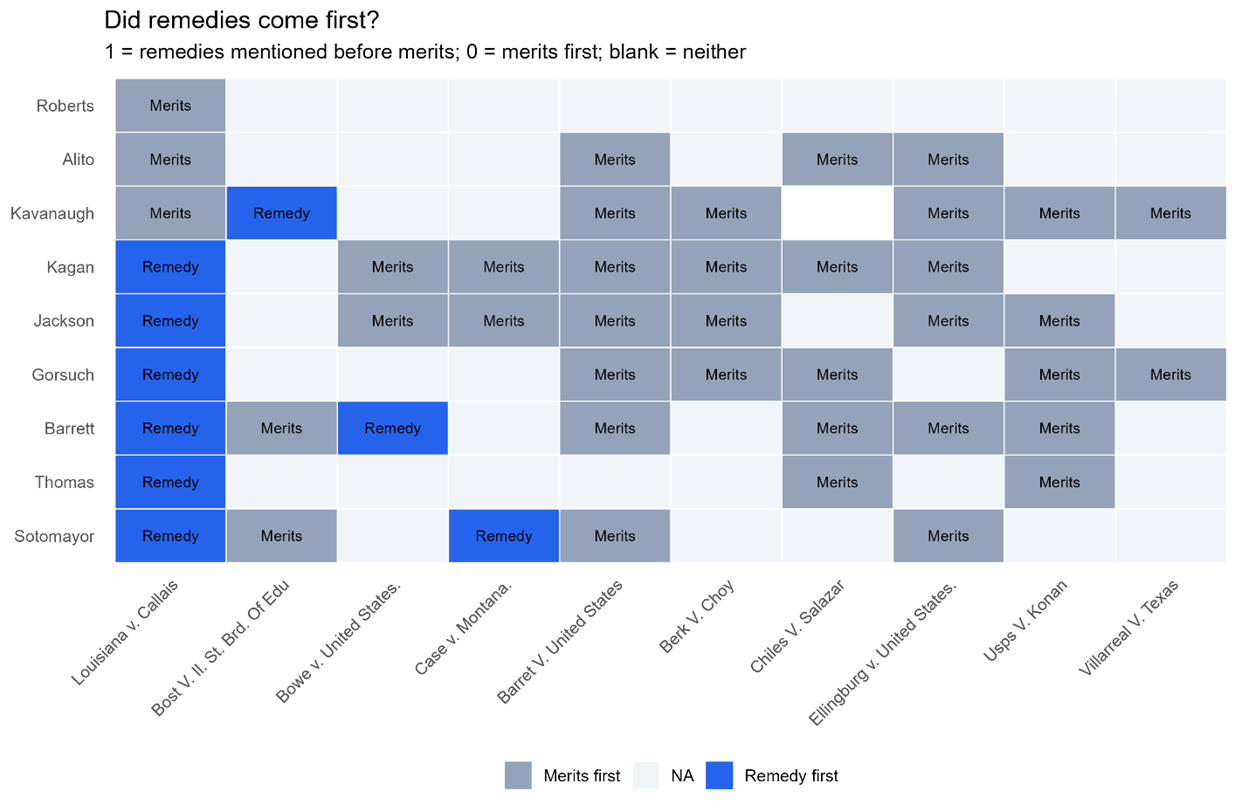

Another measure captures sequence: did a justice raise remedy words—remedy, stay, injunction, vacate—before merits language in a given sitting? In the election and pre-enforcement cases, remedies came first.

That order of operations effectively decides some cases before the Court ever reaches the substantive question. Where the only available remedy would be to throw out votes or to enjoin enforcement that the state has already promised not to pursue, the threshold does the work.

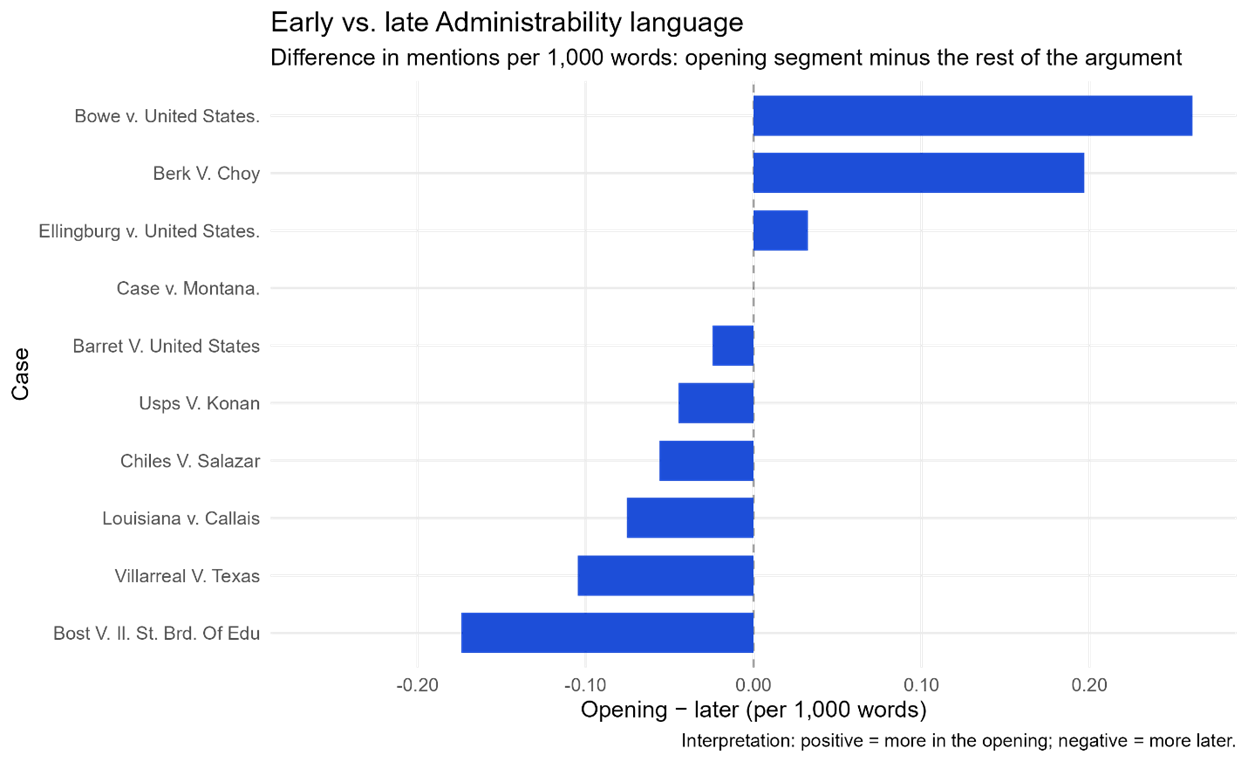

Administrability concerns appeared early and often. Mentions of workable standards, limiting principles, and the prospect of chaos or a flood of litigation were front-loaded in several arguments. The timing matters. When a Court primes the conversation with “how would this actually work?” it is testing not only the correctness of a rule but the costs of announcing it.

Read together, these patterns point to justices inclined toward limited, administrable outcomes—and help explain why some arguments never settle into a broad merits debate.

This preference for narrow, workable dispositions becomes even clearer when the Court turns to statutory text. But here the division is less about who asks the questions than about which tools the justices reach for when neighboring words in a statute seem to overlap.

Gatekeeping: Who Gets In and on What Terms

With habeas and Erie/Hanna front and center, the Court emphasized procedure over merits—doorways before destinations.

A significant share of argument time across these two weeks was devoted not to the merits but to procedure—who may be in federal court and under what conditions. Two strands dominated. The first involved AEDPA gatekeeping in habeas cases, where the question is how readily federal prisoners can obtain merits review of their claims. The second arose in a Delaware medical-malpractice case that turns on Erie and Hanna—the body of law governing when state rules apply in federal diversity cases.

These are not minor housekeeping matters. The habeas disputes determine whether prisoners get a second look at their convictions. The Erie fight will determine how far state proof-of-claim rules—here, an affidavit-of-merit requirement—can shape federal pleading practice.

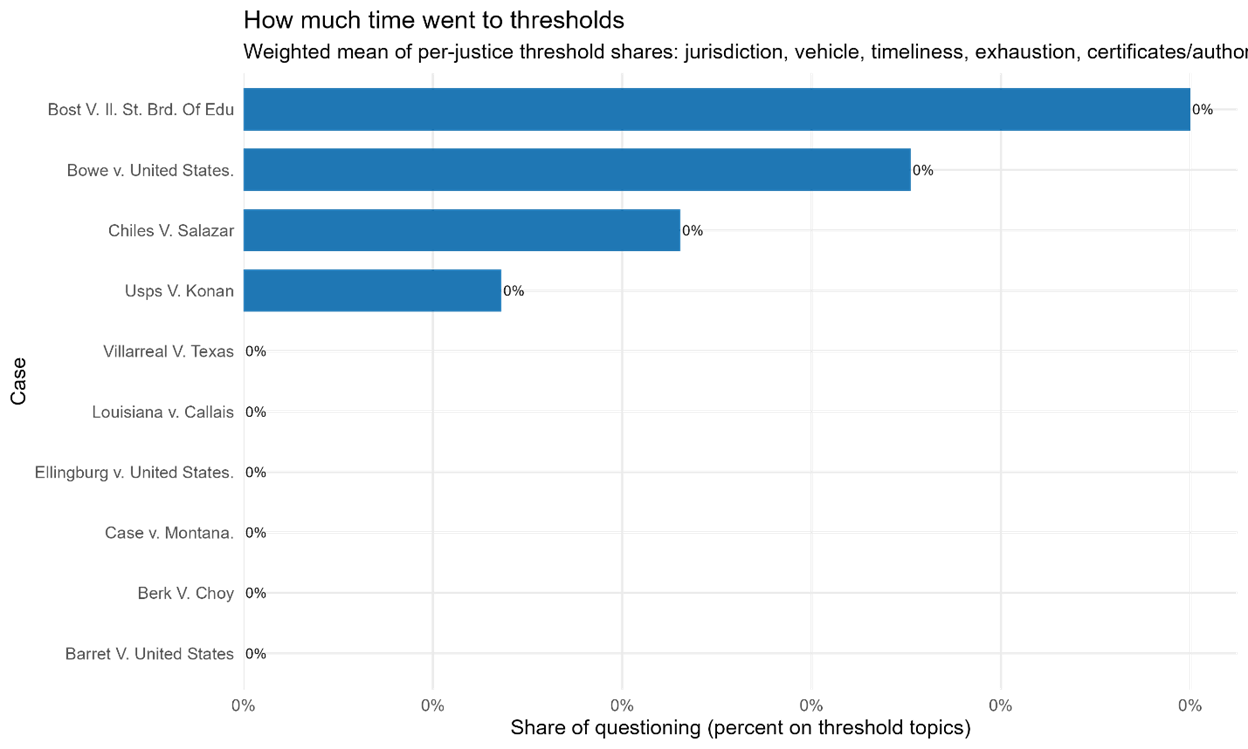

One way to measure the Court’s emphasis is to track the share of each argument devoted to threshold questions: jurisdiction, vehicle, timeliness, exhaustion, certificates of appealability, standards of review. In several arguments, these concerns dominated the justices’ questions from the outset.

Where a case shows a high threshold share, the likely outcome is a narrow, administrable disposition—authorization denied, remand for clarification, or a limited procedural rule—rather than a sweeping holding on the merits.

In the habeas cases, the bench returned repeatedly to whether AEDPA’s screening mechanisms should apply symmetrically to federal and state prisoners, and whether familiar procedural paths survive the statute as written. The questions weren’t about guilt or innocence. They were about who gets through the door.

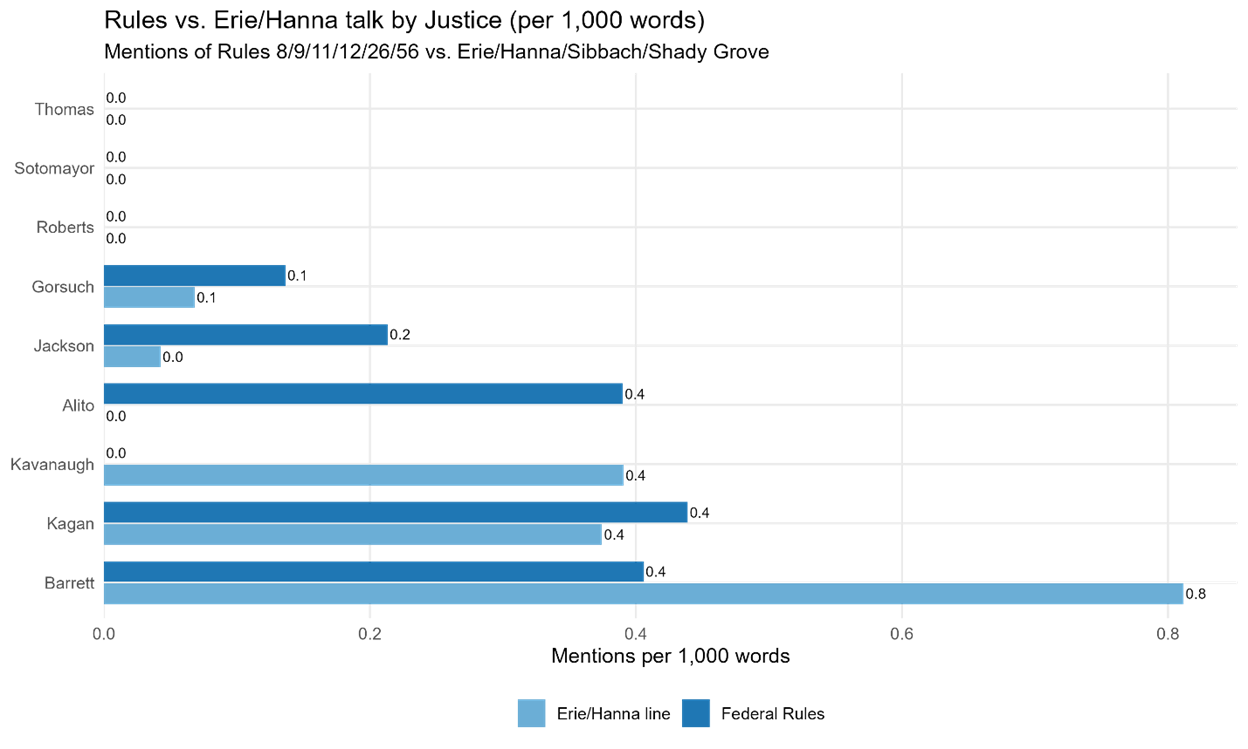

The Erie strand raised a different set of conflicts. The argument featured repeated mentions of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure—especially Rules 8, 9, 11, and 12—alongside invocations of Erie, Hanna, Sibbach, and Shady Grove, the leading cases on when federal procedural rules displace state law. The core question: does Delaware’s requirement that a plaintiff file an affidavit of merit in medical-malpractice cases coexist with the Federal Rules, or does it impose a burden at the pleading stage that the Rules don’t require?

Justice Kagan led the questioning in this case, accounting for roughly 25 percent of the justices’ words, with Justice Gorsuch close behind at about 20 percent. Their interventions reflected competing instincts—Kagan pressing the Rules conflict and the need for federal uniformity in pleading practice, Gorsuch probing whether state gatekeeping mechanisms can operate alongside federal procedure without direct collision. Justice Barrett also figured prominently, refining the remedial implications of various readings.

The pattern across both habeas and Erie cases points to a Court that has grown cautious about doctrines inviting broad, judge-made exceptions. A term that opens with gatekeeping questions in the foreground is a term likely to produce procedural holdings with real bite: tighter screening in habeas, clearer limits on state proof requirements in federal diversity cases. These outcomes won’t announce sweeping new theories. But they will reshape the path to merits decisions across a wide range of cases.

Text, Tools, and Tolerance for Overlap

When statutory words crowd each other, the Court splits between policing surplusage and accepting practical overlap.

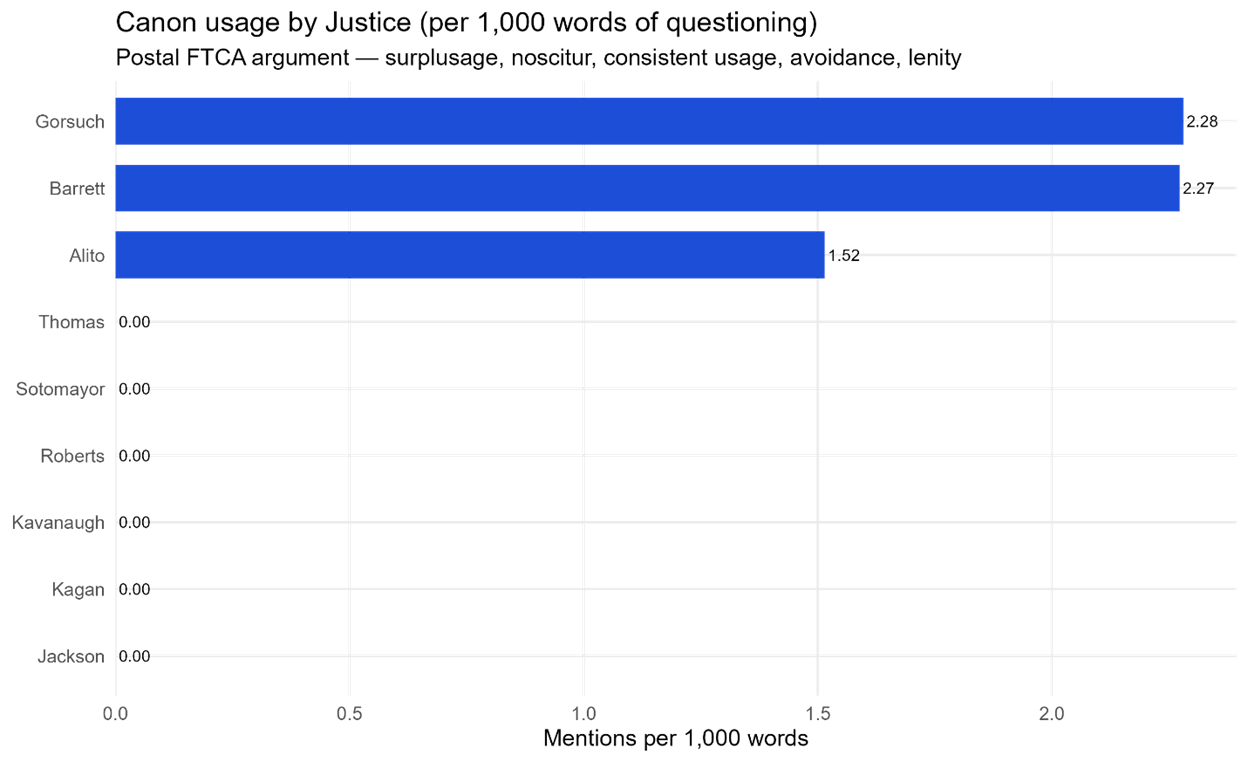

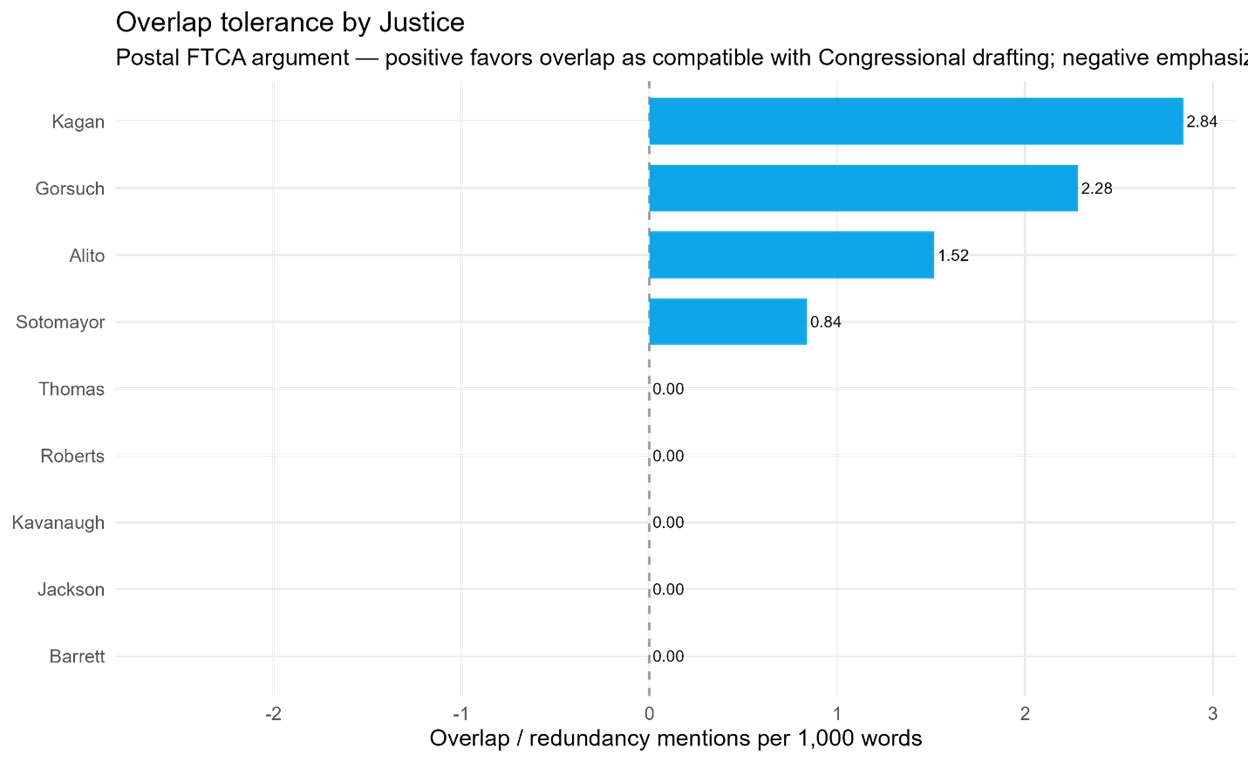

Konan offered a clean test. The relevant exception turns on three terms—”loss,” “miscarriage,” and “negligent transmission”—and the question is whether Congress meant each to carry distinct weight or whether they all point to the same idea. Over the argument, two camps emerged. On one side, justices invoked the canon against surplusage and the principle of noscitur a sociis—a Latin phrase meaning that words are known by the company they keep. If Congress used three terms, the argument goes, it must have meant three different things. On the other side, justices offered a more consequence-minded reading: these are just different ways of saying the Postal Service lost or mishandled your mail.

Justice Gorsuch pressed the redundancy problem: “there is still surplusage there... certainly with ‘miscarriage.’” Justice Kagan read the cluster as a unit: “they’re losing your letters... negligently transmitting... miscarrying... the same kind of meaning.” Justice Jackson added a pragmatic frame, asking what the claim is really about—its gravamen, in legal terms. If the harm is about the mails, the exception applies; if the harm is independent, the suit proceeds.

The data on canon usage—mentions of surplusage, noscitur, and related tools, normalized per thousand words of questioning—show who reached first for these interpretive devices. The division isn’t random. A Court comfortable with overlap in statutory language tends to read exceptions broadly. A Court that polices surplusage tends to narrow them. And the center’s tolerance for redundancy will shape several other statutory cases on this term’s docket, where the outcome may turn less on grand theory than on how much semantic slack the justices think the law can bear.

That same tension between textual precision and practical consequences runs through the criminal docket, where the Court confronted not abstract doctrine but the rules that trial judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers use every day.

Criminal Procedure in Practice

The criminal docket pressed for rules with courtroom traction—field-usable standards over high theory.

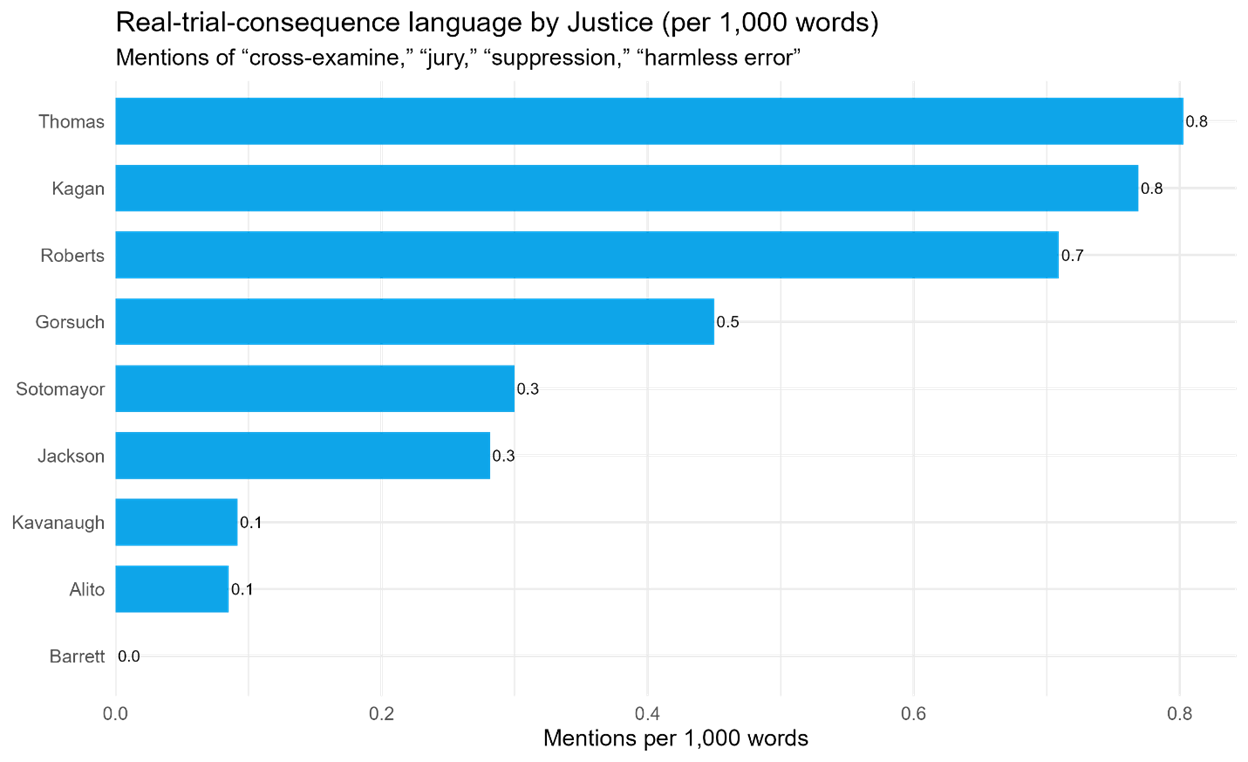

The criminal cases from these two weeks asked the Court to draw lines that can actually be applied in courtrooms: Can cross-examination probe what a defendant discussed with his lawyer during an overnight recess? What counts as exigent enough to enter a home without a warrant? Is mandatory restitution a form of punishment for constitutional purposes? And does the federal ban on concurrent sentences in gun cases apply to multiple convictions at a single sentencing hearing?

In the recess-consult case, defense counsel emphasized the stakes in practical terms: “During an overnight recess, the defendant and his counsel have a lot that they need to talk about... These are basic discussions that any competent lawyer would have with a client... Counsel has an obligation to prevent the defendant from committing perjury.” The bench then pressed how to cabin cross-examination so that the Sixth Amendment right to assistance isn’t swallowed by impeachment. The question wasn’t about high theory. It was about what trial judges do when the jury goes home for the night.

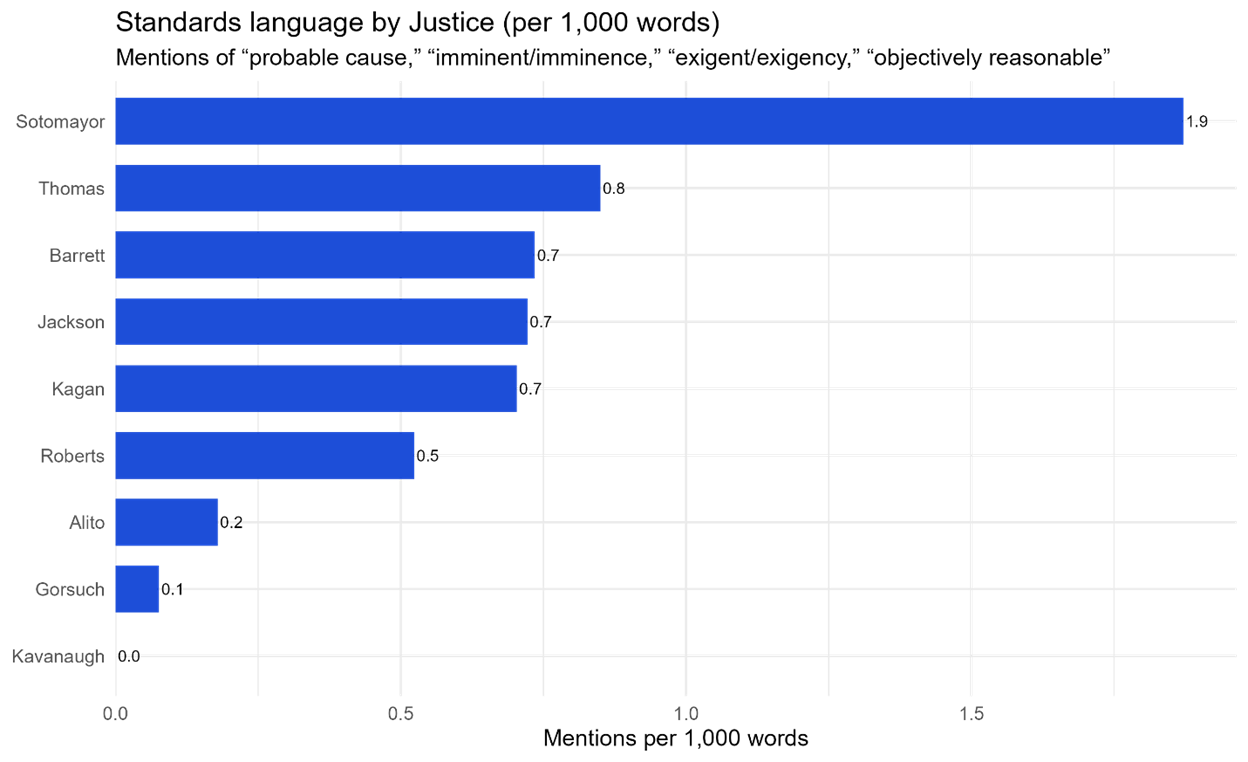

The home-entry case turned on vocabulary that officers need to apply at the threshold. The Chief Justice questioned the government’s framework—”I’m not sure why ‘probable’ is a good word”—while others worked through the factors that matter in real time: probable cause, exigency, imminence. One exchange captured the practical focus: whether someone is “seriously injured or imminently threatened” enough to justify entry without a warrant. Whatever the Court decides, the opinion will serve as a field manual for officers deciding whether to wait.

Tracking the standards language—mentions of probable cause, imminence, exigent circumstances, objectively reasonable—shows which justices did the most to pin down the test that lower courts will apply. Justice Sotomayor led in this regard, particularly in the home-entry case, pressing how standards would work when officers have seconds to decide. Justices Jackson and Kagan also concentrated on what the data capture as “real-trial-consequence” vocabulary: cross-examination, jury instructions, suppression, harmless error. This is the language of courtroom management, and the justices who used it most were testing whether proposed rules would actually function in practice.

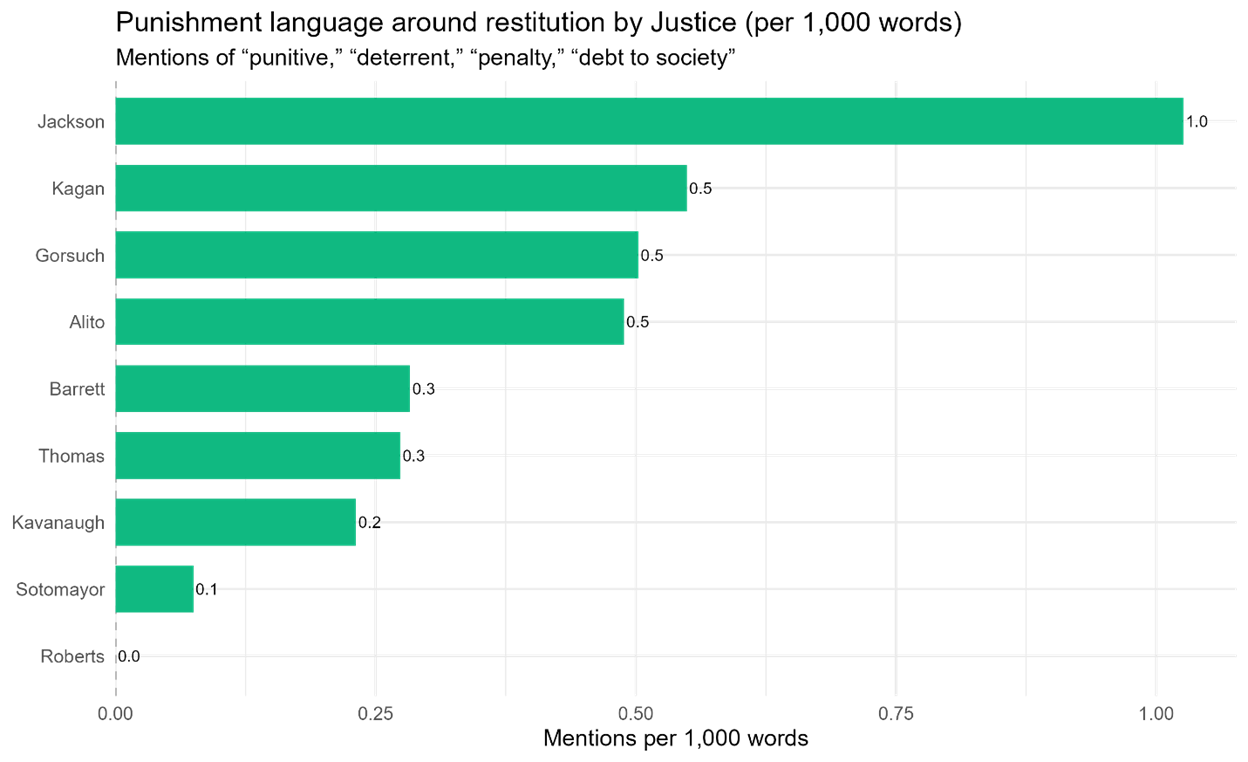

The restitution case raised a different kind of line-drawing problem. Several justices described mandatory restitution in terms that carry constitutional consequences—as “part of the debt to society,” serving penological ends like deterrence. That framing matters. If restitution is punishment, it triggers Ex Post Facto and Sixth Amendment constraints. The justices who used punishment language most frequently in their questions—debt to society, punitive, deterrent—were signaling that the Court might treat restitution awards as criminal sanctions for constitutional purposes.

In the firearms-sentencing case, Justice Kavanaugh accounted for roughly 31 percent of the questioning, an outsized share that matched his focus on the statutory text: “no term of imprisonment... shall run concurrently.” His interventions reflected the same instinct visible in the standing section—a concern with what the law actually says and what remedies flow from it.

These criminal cases point toward a term in which the Court may favor clear, workable lines in police-powers disputes, preserve room for trial judges to manage lawyer-client consultations, and treat mandatory restitution as close enough to punishment to matter. But the Court’s caution about announcing broad rules showed up most clearly in cases where the threshold question was simply whether federal court was the right forum at all.

Where the Justices Engaged

Engagement concentrated where thresholds and consequences met; the who/where distribution explains the themes above.

The distribution of questioning across individual cases tells us not just who spoke most overall, but where each justice chose to deploy their limited time and attention. Two visualizations capture this pattern: one showing raw word counts by justice in each argument, the other displaying each justice’s share of the total questioning within a case. Read together, they reveal which issues drew sustained engagement from which justices—and help explain the contours of the term ahead.

Justice Jackson dominated several arguments, most notably the Postal Service case, where she accounted for roughly 34 percent of the justices’ words. That concentration makes sense given the substance: Jackson was advancing the gravamen framework, asking what the case was really about rather than parsing statutory synonyms. She also held the largest share in the Louisiana redistricting case at about 21 percent, pressing standing and remedy questions from the opening minutes. These weren’t scattered interventions across many cases; they were sustained engagement where threshold and consequence questions intersected.

Justice Kagan’s footprint was similarly concentrated but in different terrain. She led the Illinois election case at roughly 19 percent and the Delaware medical-malpractice dispute at about 25 percent. The pattern fits: Kagan has long pressed standing requirements in election litigation, and the Erie case turned on exactly the sort of Rules conflict—whether state pleading requirements can operate in federal court—that engages her institutional concerns about federal procedure. Her questioning in these arguments wasn’t about volume for its own sake; it was about steering the conversation toward questions of federal court authority and the architecture of civil litigation.

Justice Kavanaugh’s most striking concentration came in the firearms-sentencing case, where he accounted for roughly 31 percent of the questioning—an outsized share that reflected his focus on statutory text. The case turned on whether the phrase “no term of imprisonment... shall run concurrently” bars concurrent sentences when multiple gun convictions are handed down at a single sentencing hearing. Kavanaugh’s repeated returns to that language mirrored his approach in other cases: parse what the statute actually says before worrying about the consequences. That same textual instinct surfaced in his remedial questions in the election disputes—”What’s the remedy—do you throw out those votes?”—where the statute’s requirements drove his inquiry.

Justice Gorsuch’s concentration tells a different story. He figured prominently in both the Delaware Erie case—about 20 percent of the questioning—and the Postal Service statutory dispute. In both, he pressed the same concern: what does the text permit, and where are courts stretching it? His surplusage objections in the Postal case and his probing of Federal Rules conflicts in the Erie case reflect a broader jurisprudential commitment. Gorsuch is least comfortable when courts create exceptions or balance interests that the text doesn’t explicitly authorize. His engagement in these cases signaled where he sees the Court’s institutional role most clearly: enforcing what the law says, not what it might accomplish.

Justice Sotomayor’s share was highest in the Montana criminal case at about 25 percent and remained substantial in the home-entry dispute at roughly 19 percent. Both cases asked the Court to announce standards that officers and trial judges must apply in real time—what counts as exigent, when is someone imminently threatened, how does a judge manage cross-examination of overnight consultations with counsel? Sotomayor’s sustained questioning in these arguments reflects a long-standing concern with how constitutional rules actually function in practice. She wasn’t testing legal theory; she was testing whether the proposed standards would work when a police officer has seconds to decide or when a trial judge rules at midnight with a jury waiting.

The Chief Justice’s engagement was more targeted. His share rose most noticeably in the overnight-recess case at about 12 percent, where the question was how to cabin cross-examination without undermining the Sixth Amendment. Elsewhere he intervened less but often at pivotal moments, narrowing the dispute and pressing counsel on the workability of proposed rules. That pattern—shorter turns, strategic timing—suggests a justice managing the argument toward a narrow resolution rather than driving it toward a broad one.

Justices Alito and Barrett maintained steady presences across multiple arguments. Alito’s shares were mid-to-high in the habeas case at about 17 percent and the Postal dispute at roughly 15 percent, reflecting his attention to both textual precision and practical consequences. Barrett figured prominently in the pre-enforcement challenge and the home-entry case, often refining standing theories and exploring what remedies would follow from various rulings. Her interventions tracked the themes from earlier sections: remedy first, merits second, and always with an eye to how the decision will constrain lower courts.

Justice Thomas spoke least overall, but his interventions in the habeas and election cases went to first principles—questions of federal court jurisdiction and the scope of federal power over state processes. Those contributions, though brief, often reframed the terms of the argument.

What Oral Argument Tells Us That the Shadow Docket Cannot

Oral argument surfaces the Court’s method—who prioritizes standing, who polices text, who stress-tests real-world impact.

The justices’ questioning across these first two weeks reveals something the shadow docket’s terse orders never can: how the Court reasons through hard cases when it has time to do so. Emergency applications arrive with minimal briefing and no oral argument. The Court rules quickly, often in a few sentences, and the public sees only the result. We don’t know which justice pressed for a stay or why, what alternatives were considered, or how the decision might apply beyond the immediate dispute.

Oral argument is different. It exposes the fault lines. It shows which justices care most about standing, who reaches first for textual canons, who presses hardest on real-world consequences. It reveals not just outcomes but the paths the Court might take to get there—and the paths it is determined to avoid.

The distribution of questioning across these two weeks aligns with four themes that seem likely to recur. Where standing and remedies set the agenda, the most active voices were Justices Jackson and Kagan, with Justice Kavanaugh often marking the remedial edge cases. In the tension between canons and consequences, Justice Gorsuch framed the textualist pole—policing redundancy and surplus language—while Justice Jackson advanced the gravamen inquiry, asking what a case is really about. Justice Kagan often mediated between them, looking for readings that respect text without ignoring practical effects.

On criminal-procedure questions, Justices Sotomayor, Jackson, and Kagan concentrated on standards that trial judges can actually use. The Chief Justice and Justice Gorsuch pressed how those standards would operate at the threshold—testing administrability before committing to a rule. In the gatekeeping and Erie disputes, Justice Kagan led the discussion with Justice Gorsuch close behind, a configuration that suggests the Court may favor procedural holdings with practical consequences over sweeping merits rules.

Justices Alito and Barrett were steady presences throughout, Alito pressing both textual precision and practical fallout, Barrett refining standing theories and the remedial implications of proposed rules. Justice Thomas spoke least overall but intervened pointedly in the habeas and election cases, his questions going to first principles of jurisdiction and federal power.

What This Reveals

Read across the distributions, the Court’s center of gravity is procedural—and that choice may define the term more than any single merits holding.

What emerges from this distribution is not a unified Court but a collection of justices whose engagement patterns align with distinct concerns. Where standing and remedies dominated, Jackson and Kagan led the questioning, with Kavanaugh pressing the remedial edge cases. Where statutory text was in tension with practical consequences, Gorsuch and Jackson framed the poles—one insisting on textual fidelity, the other asking what the claim is really about—while Kagan worked to mediate. In criminal cases raising administrability concerns, Sotomayor, Jackson, and Kagan concentrated on standards trial judges can use; the Chief Justice and Gorsuch pressed how those standards would operate at the threshold. And in the procedural gatekeeping cases—habeas and Erie—Kagan and Gorsuch drove the discussion, with Barrett and Alito close behind.

These patterns matter because the Court’s October sittings often preview the term. The cases themselves may not be the most prominent on the docket, but the questions the justices ask and where they concentrate their attention signal what to watch for in bigger cases ahead. A Court that opens the term by front-loading threshold questions, testing remedies before reaching the merits, and asking whether proposed rules will work in practice is a Court preparing to decide narrowly when it can.

That preference for caution and administrability runs through all four themes that emerged from these arguments. It suggests a term likely to be defined as much by procedural architecture as by grand pronouncements—a term in which the most consequential rulings may be the ones that reshape who gets into federal court and on what terms, rather than the ones that announce new constitutional principles.

These first two weeks suggest the Court is taking its time—narrowing where it can, pressing for workable standards, and showing more interest in how decisions will be applied than in how they will read in a casebook. Whether that caution holds as the term progresses and as more politically charged cases arrive remains to be seen. But the early signals, captured in thousands of words of questioning and in the patterns of who asked what when and where, point toward a Court more concerned with the mechanics of judging than with making headlines. That may be the most important story these arguments have to tell.

Thanks to Daniel Thompson in helping to get this article together.

To subscribe, share, or comment

I find this analysis absolutely fascinating, investigating avenues I never knew existed.

But somehow I get the impression that this Court is more interested in clockwork than who winds the clock … and why. Is the rule of law valid when enacted by the lawless?