Legalytics Report 4/9/2025

Analysis of the Associated Press court opinion from DC and the Samsung oral argument from the Federal Circuit

* This is the first edition of a new column I hope to run several times a week that takes a deep dive into one or more recent opinions or oral arguments of note across all courts. I’m trying out new tools for non-Supreme Court oral arguments where I try to identify individual judge and attorney speakers with audio software tools. While the text of the transcript is clear, the attribution of specific speech to particular judges may in some instances be in error based on this new method.

Opinion in Associated Press v. Budowich, et al.

U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia | April 8, 2025 | Case No. 1:25-cv-00532 (TNM) [Link]

Judge: Trevor N. McFadden

📰 What the Case Is About

In early 2025, President Donald Trump officially renamed the "Gulf of Mexico" the "Gulf of America." The Associated Press (AP) chose not to adopt that change in its journalism. In response, senior White House officials sharply limited the AP’s access to high-profile events—particularly those involving the President. The AP filed a lawsuit, arguing that this exclusion was retaliation for its editorial stance and violated the First Amendment.

Judge Trevor McFadden sided with the AP, issuing a preliminary injunction ordering the bedrock principle: government officials can’t use selective access as a reward for favorable coverage—or punishment for dissent.

The Court's Decision: What It Means

The AP won—for now. Judge McFadden ruled that the AP is likely to succeed on its core claims: that the White House unlawfully discriminated based on viewpoint and retaliated against the AP for exercising its First Amendment rights.

This ruling doesn't give the AP special access. It simply restores the outlet’s right to compete on equal footing with other journalists. It doesn't force the White House to admit any particular outlet to every event—but it does bar officials from blacklisting the AP for refusing to adopt political language.

The White House can still limit press access for legitimate reasons like space, security, or scheduling. But it can't shut the door to disfavored outlets just because they don’t echo the President’s messaging.

Who Represented the Winning Side

The Associated Press was represented by in-house counsel and supported by amicus briefs from groups including the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, which emphasized the constitutional importance of press independence and viewpoint neutrality.

Judge and Judicial Leanings

Judge Trevor N. McFadden, appointed by President Trump in 2017, wrote the opinion in this case.

McFadden’s Background: Known for textualist leanings and often deferential rulings on executive authority, McFadden’s decision here stands out for strongly defending press freedoms—even when the press is critical of the executive.

His ruling heavily leans on First Amendment precedent and a history-rich explanation of press rights, suggesting a commitment to perceived originalist constitutional values.

Values

The decision was rooted in constitutional doctrine. McFadden applied well-established First Amendment principles: even in limited-access spaces like the Oval Office or East Room, the government can’t discriminate based on viewpoint.

While political tension looms over the facts, the judge’s analysis remained focused on legal standards, not political judgments. He emphasized that once the government opens a forum to some reporters, it must treat all journalists fairly—regardless of how they describe a body of water.

Judicial Philosophies at Work

Textualism & Originalism: McFadden’s lengthy discussion of early American press freedoms and Anti-Federalist views reflects a deep originalist approach—tracing First Amendment protections to their historical roots.

Pragmatism on Process: Although conservative in background, McFadden took a practical view of harm to AP's business model and real-time journalism, recognizing that modern media depends on speed and equal access.

His ruling balances historical understanding with what the judge noted as today’s realities.

Key Laws, Doctrines, and Authorities

First Amendment: The core legal framework—freedom of the press and protection from government retaliation.

Forum Doctrine: The White House press spaces were treated as “nonpublic forums,” meaning the government has some control, but cannot discriminate based on viewpoint.

Relevant Precedents:

Sherrill v. Knight (D.C. Cir. 1977): Government must follow due process in revoking press credentials.

Perry Education Ass’n (1983): Nonpublic forums can be regulated—but not based on viewpoint.

Baltimore Sun v. Ehrlich (4th Cir. 2006): Distinguished here; unlike AP’s case, that dispute involved minimal harm and no exclusion from access to press spaces.

Ateba v. Leavitt (D.C. Cir. 2025): Affirmed the limits of discretion in excluding journalists from White House spaces.

Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense Fund (1985): Even in nonpublic forums, viewpoint-based exclusions violate the First Amendment.

Opinion (Word Count: ~18,400 words)

Judge McFadden’s opinion is draws on:

Founding-era commentary on freedom of the press.

Live testimony from AP journalists on exclusion and its business impact.

Modern technological realities of real-time news gathering.

“The AP seeks restored eligibility… on the same terms as other journalists. That is all the Court orders today.”

Though from a trial court judge, this decision may influence future press access debates.

Policy Implications

Press Freedom Affirmed

This ruling sends a message to government officials: according to McFadden, you can’t penalize media outlets for disagreeing with you. Even in limited, discretionary press pools, the Constitution doesn’t allow viewpoint-based exclusion.

Wire Services and Local News Impact

Because AP’s syndication model fuels local journalism, especially small outlets without their own White House correspondents, limiting AP’s access had ripple effects. Restoring AP access restores millions of Americans’ indirect access to presidential events.

Tone, Rhetoric, and Structure

Judge McFadden’s opinion is notable for its clarity and rhetorical craftsmanship. It opens not with abstract legalese but with a vivid statement:

“No, the Court simply holds that under the First Amendment, if the Government opens its doors to some journalists… it cannot then shut those doors to other journalists because of their viewpoints.”

This tone sets the stage for an opinion that embraces constitutional seriousness while maintaining a plainspoken, almost conversational cadence. The judge uses historical narrative (with references to James Madison, Anti-Federalist pamphlets, and the Sedition Act) not just to ground the legal analysis in originalism, but also to attempt to emotionally connect press freedom to the American democratic identity. Faulkner’s famous quote cited in the opinion—“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”—further underscores that constitutional values are active constraints on government.

There’s also a subtle rhetorical arc. McFadden begins with high-minded history, moves through contemporary doctrine, then walks through the granular factual record—tightly integrating law with narrative. This structure reinforces the inevitability of McFadden’s legal conclusion: given the facts, the law, and the First Amendment’s origins as McFadden conveyed, the government’s actions cannot stand.

Doctrinal Significance: Why This Is a Major First Amendment Opinion

1. Reaffirming Viewpoint Neutrality—Even in Discretionary Contexts

This ruling builds on Sherrill v. Knight and expands it by applying viewpoint neutrality principles not just to the issuance of press credentials, but to discretionary, event-by-event access decisions. The court emphasizes that even in “nonpublic forums” like the Oval Office or East Room—where the government enjoys wide discretion—viewpoint discrimination remains off limits.

This is significant because many assumed that daily press event decisions were largely immune from judicial oversight unless credentials were revoked. McFadden pushes back: once access is opened to some journalists, viewpoint neutrality applies.

2. Government Speech Doctrine Checked

The opinion fends off any possible reliance on the government speech doctrine, which allows the government to craft its own message. McFadden explains that choosing which journalists can report is not the same as crafting a message. That distinction is crucial—it protects press independence from being absorbed into government messaging.

This line—“the act of curating the press pool is not itself a form of speech”—is key in this decision. It sharply distinguishes government communication from gatekeeping access to independent journalism, drawing a clearer constitutional boundary than some earlier courts have.

Political Subtext

Though the case is deeply political—it involves Donald Trump, media hostility, and culture war over naming conventions—McFadden’s opinion attempts to avoid partisan framing. That’s no accident. His ruling avoids ideological grandstanding and never characterizes Trump or his administration as malicious or authoritarian. Instead, it focuses on legal boundaries and process, which may subtly strengthen its legitimacy among skeptical audiences.

This approach also may make it harder for the ruling to be dismissed as political activism. Even though it limits executive power in favor of a critical media outlet, it does so by defending traditional constitutional values using traditional conservative paradigms (textualism, originalism, institutional restraint).

Media Access in the Digital Age: A Modernized View

One of the notable aspect of the decision is the court’s recognition that journalism today is real-time, multimedia, and deeply competitive. The opinion spends pages documenting how:

AP photographers transmit images from the Oval Office in under 45 seconds.

Text journalists send live updates to editors as events unfold.

Losing access—even for hours—can destroy a news outlet’s ability to break a story.

This detail matters because many older First Amendment rulings assumed a slower, print-based news cycle. McFadden recognizes that in today’s media landscape, access isn’t just a luxury—it’s the infrastructure of journalism.

What the Opinion Signals for the Future

🔹 White House Press Access Is Now a First Amendment Issue

This ruling may lead to more litigation over White House or statehouse press practices—especially where access seems to favor politically friendly outlets. Even if this opinion doesn’t bind other courts directly (being from a district court), it builds persuasive precedent and will likely be cited heavily by journalists or advocacy groups challenging exclusions.

🔹 “New Media” vs. Legacy Media Is a Legal Flashpoint

The Trump White House's justification—promoting “new media” historically excluded from coverage—hints at broader battles over who counts as legitimate press. The opinion implicitly warns that using diversity or democratization as a fig leaf for retaliation won't pass constitutional muster in certain courtrooms.

🔹 Style Guides and Editorial Judgment Are Protected

The court's insistence that the AP’s editorial choice (to stick with “Gulf of Mexico”) cannot be used against is designed to protect journalistic independence at its core. According to McFadden it is not just about access—it’s about preserving the press’s right to define its own voice, terms, and facts.

Subtle, Strong, and Future-Facing Opinion

While Judge McFadden’s opinion does not grant sweeping relief, it offers a clear and path forward for protecting press freedom. It declares that:

“All the AP wants, and all it gets, is a level playing field.”

Why This Case Matters

This case is about more than just the name of a body of water. It’s about how the government can attempt to persuade news outlets to adopt its preferred language.

The ruling stands as a First Amendment moment in the digital age, reinforcing that in this case, real-time journalism is protected speech. With the press increasingly reliant on rapid access, this decision shores up (in some instances) legal protections for how modern news is gathered and delivered.

Data

1. Opinion Word Count and Structure

Even without multiple opinions, the length and complexity of the majority opinion tells us something:

Majority Opinion: ~18,400 words

Estimated reading time: ~75 minutes

Estimated length: ~45 pages (double spaced)

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: ~13.2 (college+)

Passive voice ratio: ~11% (low—active tone)

Quotes per 1,000 words: ~3.4 (high—heavily sourced)

Why this matters: This was not a perfunctory ruling. McFadden invested significant time in building a historically rich and doctrinally nuanced opinion, suggesting the court sees the case as both consequential and likely to draw scrutiny.

2. Timeline Metrics

Key Dates and Durations

3. Frequency of AP Exclusion

From Feb 13 to March 26, AP was excluded from at least 12 specific events, including:

5 Oval Office press pool events

4 East Room or “pre-credentialed” large events

3 off-site press events (e.g., DOJ speech, tarmac)

The court credited this timeline to support the AP's claim of systematic exclusion—not isolated errors. This also helped the judge connect real-world consequences to constitutional harm, which grounded the irreparable injury finding.

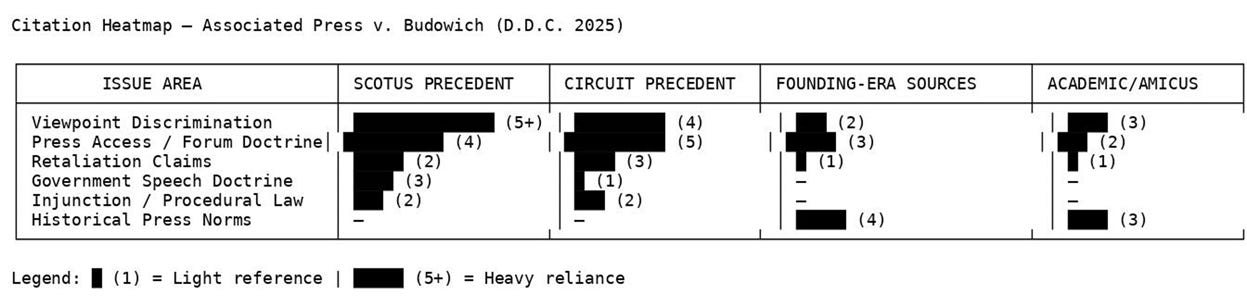

Court’s Use of Citations and Historical Sources

Interpretation and Synthesis:

Doctrinal Core: The opinion leaned heavily on First Amendment viewpoint discrimination cases (Perry, Cornelius, Rosenberger) and forum access cases (Sherrill v. Knight, Ateba, Evers).

Historical Backbone: The founding-era content—Anti-Federalist writings, the Sedition Act backlash, and Madison’s congressional defense of the press—gave the opinion moral and constitutional legitimacy, especially in the absence of Supreme Court rulings on modern press pool exclusions.

Modern Media Context: Cited academic literature and amicus briefs (particularly from the Knight First Amendment Institute) helped bridge old doctrine with today’s real-time journalism realities.

Oral Argument in Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. v. Power2B, Inc. (No. 23-2121)

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit [Link]

Panel: Judges Dyk, Stoll, and Stark

Date of Argument: April 8, 2025

Samsung challenges PTAB’s decision upholding two patents owned by Power2B—U.S. Patent Nos. ‘070 and ‘369—covering stylus-based input on digital displays. The argument centers on whether Samsung sufficiently described and supported a combination of two prior art references (Keeley and GIVA) in its original IPR petition and whether its clarifications in reply were procedurally valid or improperly introduced new theories.

PTAB held that Samsung failed to show how its proposed combination satisfied the claim limitations, particularly around:

A "touch-sensitive display" (for the ’070 patent)

"Tracking movement" (for the ’369 patent)

And a “motivation to combine” Keeley and GIVA

Samsung argues PTAB misunderstood its combination—misreading the petition to retain Keeley’s outdated digitizer rather than replacing it with GIVA’s light-based system—and improperly rejected its reply clarifications. Power2B maintains that Samsung changed theories too late and that the Board’s findings are supported under the applicable standards.

Attorney Performance

Haber (Samsung – Appellant)

Haber opened with a clear theme: PTAB failed to consider the actual combination Samsung advanced. He emphasized that the GIVA stylus and planar element were meant to replace Keeley’s electromagnetic digitizer, not supplement it, and that Keeley’s software would process GIVA’s hardware output. This, he argued, was always Samsung’s theory—even if not fully articulated until the reply brief.

He cited figures, appendices, and expert declarations (especially a clarifying reply declaration from Dr. Peterson) to argue that the reply was not new, but a response to Power2B’s misunderstanding. He pointed to places in the petition where Samsung discussed GIVA’s advantages over electromagnetic systems and where the combination was visually depicted.

Strengths:

Strong grasp of record details and legal standards

Responsive to questions about ambiguity and reply limitations

Positioned the combination as logically necessary and technically consistent

Weaknesses:

Some overreliance on what was “intended” rather than what was clearly written

Judges pressed him on whether key aspects of the theory appeared in the original petition

Difficulty proving that the specific Keeley-GIVA hybrid was ever unambiguously described pre-reply

Deming (Power2B – Appellee)

Deming focused on procedure. He argued that Samsung’s petition did not clearly disclose the Keeley-software-plus-GIVA-hardware combination and instead appeared to rely on Keeley’s display and digitizer. The reply, he said, introduced a new combination, which is barred under IPR rules. He further argued that even the clarified combination still failed to satisfy the patent claims and lacked adequate support.

He walked the court through the Board’s findings that Samsung was mixing incompatible technologies or removing key touch-sensitive components without functional replacement.

Strengths:

Consistent procedural framing: “Samsung shifted theories too late”

Effectively pointed to record ambiguity and Board findings

Reminded court of deferential standard (abuse of discretion)

Weaknesses:

Less persuasive when judges asked if the reply was at least responsive

Couldn’t fully explain why expert deposition wasn’t sought to resolve ambiguity

Didn’t clearly rebut that GIVA's planar element could fulfill the missing functionality

Judge Analyses (based on presumptive judges for each statement)

Judge Stark

Stark was the most active and central voice throughout. His questioning focused on the distinction between new arguments and clarifications, the adequacy of petition disclosures, and the Board’s understanding.

He repeatedly pressed both sides:

“Isn’t it clear that the reply theory, whether a clarification or new, was responsive to the argument you were making?”

He also expressed skepticism about the Board’s purported consideration of the reply theory:

“They say they considered it, but did they really consider the theory as presented?”

Stark also flagged the sentiment behind Samsung’s reply—namely that it corrected Power2B’s misreadings rather than inventing a new theory.

Tone: Constructive and slightly supportive of Samsung

Judicial Priority: Procedural fairness, record clarity

Vote Prediction: Leaning to reverse and remand for reconsideration of the actual combination

Judge Dyk

Dyk adopted a more textual and deferential stance, homing in on what Samsung’s petition actually said. He challenged Haber on whether GIVA’s planar element and Keeley’s software were explicitly described as the working combination.

When discussing the Board’s rejection of “movement tracking” in the ’369 patent, Dyk was skeptical of Samsung’s reliance on GIVA’s limited capabilities:

“Isn't the fact that GIVA’s z-axis detection is rough at best part of why the Board was right to reject that claim?”

Dyk also highlighted the standard of review—abuse of discretion—and seemed reluctant to disturb the Board’s weighing of the evidence.

Tone: Skeptical and exacting

Judicial Priority: Deference to administrative fact-finding

Vote Prediction: Likely to affirm

Judge Stoll

Stoll was the least active, making only a few interventions. Her questions focused on procedural clarity, particularly around what each party meant by “sensors” and whether Samsung’s petition could reasonably be read as including or excluding the Keeley digitizer.

Though limited in words, her tone suggested concern over the clarity of the petition. She appeared open to the idea that the reply clarified rather than created the GIVA+Keeley theory, but she didn’t strongly tip her hand.

Tone: Neutral to mildly inquisitive

Judicial Priority: Fair notice and logical coherence

Vote Prediction: Toss-up, possibly siding with Stark if she sees the reply as valid elaboration

Insights from Background

Judge Stark has previously ruled in favor of reply flexibility when tied to responsive elaboration.

Judge Dyk tends to be formalistic about administrative procedure, often siding with the PTAB unless error is clear.

Judge Stoll often takes a middle-ground approach, weighing procedural clarity and outcome fairness.

Vote Prediction Summary

Overall Prediction: Split panel—possible 2-1 for partial reversal and remand, depending on how Stoll votes.

Data

Word Count Summary (Approximate)

This chart shows estimated word counts spoken by each judge, broken down by who they addressed—Samsung (appellant) or Power2B (appellee):

Judge Stark led the questioning with around 1,900 words, heavily focused on Samsung (1,100 words), but still engaging Power2B (800 words). His intensive questioning reflects his central role in pressing both legal theory and procedural fairness.

Judge Dyk spoke approximately 1,400 words, with a slight lean toward Samsung as well. His focus was on textual clarity and administrative deference.

Judge Stoll had the lightest presence, with about 500 words evenly split between the two parties—indicating a more observational or measured approach.

Stark shaped the oral argument’s direction. The fairly balanced attention across parties suggests the panel gave both sides meaningful engagement, but the intensity and tone of that engagement varied.

Judge Intervention Timeline (45 Minutes)

Stark: Most vocal, concentrated around the 10–35 minute mark

Dyk: Increasing engagement mid-argument, tapering late

Stoll: Light and steady engagement, mostly in the middle third

Sentiment Analysis Description

The sentiment map uses a simplified numerical scale to capture the tone each judge took toward the two parties:

+1 = Supportive

0 = Neutral

−1 = Confrontational

Here’s how the judges mapped out based on their questioning tone and content:

Judge Stark

To Samsung: +0.3

Stark showed a constructive tone toward Samsung. While he asked probing and complex questions, they aimed to clarify misunderstandings and seemed motivated by a desire to ensure Samsung’s position was fairly evaluated. For example, he explored whether Samsung’s reply was truly “new” or a legitimate response to Power2B's misunderstanding.To Power2B: −0.3

His tone toward Power2B was more skeptical. He questioned whether Power2B (and the Board) had fairly considered Samsung’s combination and reply evidence. This tone suggests concern about procedural overreach or narrow interpretation by the PTAB.

Judge Dyk

To Samsung: −0.2

Dyk's tone leaned more critical of Samsung’s argument. He emphasized whether the petition was internally consistent and explicitly clear, often casting doubt on whether the theory Samsung later presented was actually present at the outset.To Power2B: +0.2

He was affirming and supportive of Power2B’s position that the Board acted within its discretion. His tone reflected confidence in the procedural sufficiency of Power2B’s interpretation.

Judge Stoll

To Samsung: 0.0

Judge Stoll maintained a neutral tone. She asked clarifying questions but avoided showing preference or skepticism. Her minimal engagement and even-handed comments suggest she was listening closely but withholding judgment.To Power2B: +0.1

Slightly more positive tone, mostly in the form of affirming questions or subtle signals that she followed their reasoning. However, her limited participation kept her overall tone restrained.

The sentiment map suggests a tonal divide on the panel. Stark appears receptive to Samsung’s procedural fairness argument, Dyk is deferential to the PTAB and more critical of Samsung, and Stoll is balanced but subtly tilting toward affirming. This tonal landscape helps forecast the ideological and procedural weight behind each judge’s potential vote.

If you enjoyed this article please think about subscribing and sharing it with others

As to the Samsung case — my mind stopped; it’s like watching an uncaptioned film where everyone speaks calculus, fascinating but incomprehensible (at least to me).

A new - and welcome - addition to the Legalytics arsenal—congratulations!